Liberty Square (自由廣場), Taipei, Taiwan. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2019. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

PPTELL Conference

Taipei, Taiwan

3-5 July 2019

The second Pan-Pacific Technology-Enhanced Language Learning Conference took place over three days in midsummer in Taipei, with a focus on language learning within smart learning environments.

In his keynote, In a SMART world, why do we need language learning?, Robert Godwin-Jones spoke of visions of a world with universal machine translations; innovations in this area range from phone translators and Google Pixel Buds to devices like Pocketalk and Illi. But it’s time for a reality check, he suggested: it’s not transparent communication because you have to awkwardly foreground the device; there are practical issues with power and internet connections; and although the devices are capable with basic transactional language, the user remains on the outside of the language and the culture.

We are now seeing advances in AI thanks to deep learning and big data, including in areas such as voice recognition and voice synthesis, and we are seeing a proliferation of smart assistants and smart home devices; along with commercial efforts, there are efforts to create open source assistants. Siri and Google can operate in dozens of languages. Amazon’s Alexa now has nearly 100,000 ‘skills’ and users are being invited to add new languages. Smart assistants are already being used for language learning, for example for training pronunciation or conversational practice. We are gradually moving away from robotic voices thanks to devices such as Smartalk and Google Duplex; assistants such as the latter work within a limited domain, making the conversation easier to handle, but strategic competence is needed to avoid breakdowns in communication. Likely near-term developments include more improvements in natural language understanding, first in English, then other languages, and voice technology being built into ever more devices (with human-sounding voices raising questions of trust and authenticity). However, there are challenges because of the issues of:

- cacophony (variations of standard usage, specialised vocabulary, L2 learners, the need for a vast and continuously updated database);

- colour (idioms, non-verbal communication);

- creativity (conventions may change depending on context, tone, individual idiosyncrasies);

- culture (knowing grammar and vocabulary only gets you so far, as you need to be able to adapt to cultural scripts, and to develop pragmatic competencies);

- codeswitching (frequent mixing of languages, especially online, in a world of linguistic superdiversity).

There is emerging evidence that young people are learning languages informally online, especially English, as they employ it for recreational and social purposes (see: Cole & Vanderplank, 2016). We may be moving towards a different conception of language relating to usage-based linguistics, which is about patterns rather than rules. It may call into question the accepted dogma of SLA (the noticing hypothesis, intentionality, etc) and the idea that learning comes from explicit instruction. However, there are caveats: most studies focus on English and on intermediate or advanced learners, who may not be reflecting much on their language learning.

The scenario we should promote is one where we blend formal and informal learning. For monolinguals and beginners, structure is helpful; for advanced learners, fine-tuning may be important. Teachers may model learner behaviour, and incorporating virtual exchange is easier when there is a framework. There are also issues with finding appropriate resources for a given individual learner. Some possible frameworks for thinking about this situation include:

- structured unpredictability (teacher supplies structure; online resources supply unpredictability and digital literacy; students move from L2 learners to L2 users; a formal framework adds scope for reflection and intercultural awareness – Little & Thorne, 2017);

- inverted pedagogy (teachers should be guides to what students are already learning outside class – Socket, 2014);

- bridging activities (students act as ethnographers selecting content outside the classroom as they build interest, motivation and literacy – Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008);

- global citizenship (students learn through direct contact and building critical language awareness through telecollaboration);

- serendipitous learning (we should have a learner/teacher mindset everywhere; there is a major role for place-based learning and mobile companions using AR/VR/mixed reality – Vazquez, 2017).

Smart technology can help through big data and personalised learning, including language corpora. In the future, smart will get smarter, he suggested. More options will mean more complexity; the rise of smart tech + informal SLA = something new. There will be more variety of student starting points, identities, and resources; we could consider the perspective supplied by complexity theory here. We need to rethink some standard approaches in CALL research:

- causality, going beyond studies of single variables;

- individualisation, because one size doesn’t fit all;

- description, not prediction;

- assessment, which should be global and process-based in scope;

- longitudinal approaches, picking up learning traces (see the keynote by Kinshuk, below).

A possible way forward for CALL research, he concluded, is indicated by Lee, Warschauer & Lee, 2019.

In his keynote, Smart learning approaches to improving language learning competencies, Kinshuk pointed out that education has become more inclusive, taking into account the needs of all students, and focusing on individual strengths and characteristics. There are various learning scenarios, both in class and outside class, which must be relevant to students’ living and work environments. There is a focus on authentic learning with physical and digital resources. The overall result is a better learning experience.

Learning should be omnipresent and highly contextual, he suggested. We need seamless learning integrated into every aspect of life; it should be immersive and always on; it should happen so naturally and in such small chunks that no conscious effort is needed to be actively engaged in it in everyday life. Technologies provide us with the means to realise this vision.

Smart learning analytics is helpful because it allows us to discover, analyse and make sense of student, instruction and environmental data from multiple sources to identify learning traces in order to facilitate instructional support in authentic learning environments. We require a past record and real-time observation in order to discover a learner’s capabilities, preferences and competencies; the learner’s location; the learner’s technology use; technologies surrounding the learner; and changes in the learner’s situational aspects. We analyse the learner’s actions and interactions with peers, instructors, physical objects and digital information; trends in the learner’s preferences; and changes in the learner’s skill and knowledge levels. Making sense is about finding learning traces, which he defined as follows: a learning trace comprises a network of observed study activities that lead to a measurable chunk of learning. Learning traces are ‘sensed’ and supply data for learning analytics, where data is typically big, un/semi-structured, seemingly unrelated, and not quite truthful (with possible gaps in data collection), and fits multiple models and theories.

In the smart language learning context, he mentioned a smart analytics tool called 21cListen, which allows learners to listen to different audio content and respond (e.g., identifying the main topic, linking essential pieces of information, locating important details, answering specific questions about the content, and paraphrasing their understanding), and analyses their level of listening comprehension depending on the nature and timing of their responses. Analytics does not replace the teacher, but gives the teacher more tools; and as teachers give feedback, the system learns from them and improves. Work is still underway on this project, with the eventual aim of producing a theory of listening skills. He went on to outline other tools taking a similar analytics approach to reading, speaking and writing.

In his keynote, Learning another first language with a robot ‘mother’ and IoT-based toys, Nian-Shing Chen spoke of the advantages of mixed-race babies growing up speaking two languages, a situation which could be mimicked with the use of a robot ‘mother’ speaking a language other than the baby’s mother tongue. This, he suggested, would help to solve L2 and FL learning difficulties indirectly but effectively. It would deal with issues of age (the need for extensive language exposure before the age of three), exposure (with children in language-rich households receiving up to 30 million words of input by age three), and real ‘human’ input (since when babies watch videos or listen to audio, they do not acquire language as they do from their mothers).

His design involves toys for cultivating the baby’s cognitive development, a robot for cultivating the baby’s language development, and the use of IoT sensors for the robot to be fully aware of the context, including the interaction situation and the surrounding environment. The 3Rs (critical factors for effective language learning design) are, he said, repetition, relevance and relationship. The idea is for the robot to interact with the baby through various toys. He is currently carrying out work on various types of robots: a facilitation robot, a 3D book playing robot, a storytelling robot, a Chinese classifiers learning robot, and a STEM and English learning robot.

NTNU Linkou Campus (台師大·林口校區), Taipei, Taiwan. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2019. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

In his presentation, Autonomous use of technology for learning English by Taiwanese students at different proficiency levels, Li-Tang Yu suggested that technology offers many opportunities for self-directed learning, which is important as students need to spend more time learning English outside of their regular classes. In his study, he found there was no significant difference between high and low proficiency English learners in terms of the amount of autonomous technology-enhanced learning they undertook. Most students in both groups mentioned engaging in receptive skills activities, but the high proficiency students engaged in more productive skills activities. Teachers should familiarise students with technology-enhanced materials for language learning, and recommend that they undertake more productive activities.

In her talk, Online revised explicit form-focused English pronunciation instruction in the exam-oriented context in China, Tian Jingxuan contrasted the traditional method of intuitive-imitative pronunciation instruction with newer and more effective form-focused instruction; in revised explicit form-focused instruction, there is a focus on both form and meaning practice. In her study, she contrasted traditional instruction (control group) with revised explicit form-focused instruction (experimental group, which also undertook after-class practice) in preparing students for the IELTS exam in China. Participants in the experimental group performed better in both the immediate and delayed post-test; she concluded that revised explicit form-focused instruction is more effective in preparing students for their exams, at least in the case of the low-achieving students she studied.

In the paper, Investigating learners’ preferences for devices in mobile-assisted vocabulary learning, Tai-Yun Han and Chih-Cheng Lin reported on a study of the device preferences of 11th grade EFL students in Taiwan, based on past studies conducted by Glenn Stockwell in Japan. The most popular tool for completing vocabulary exercises was a mobile phone, followed by a desktop PC, laptop PC and tablet PC; students’ scores were similar, as was the amount of time required to complete the tasks. In general, students have high ownership of mobile phones and low availability of other devices (unlike the college students in Stockwell’s studies), and are accustomed to mobile lives.

In his paper, Perceptions, affordances, effectiveness and challenges of using a mobile messenger app for language learning, Daniel Chan spoke about the use of WhatsApp to support the teaching of French as a foreign language in Singapore. It has many features that are useful for language teaching, e.g., the recording of voice messages, the annotating of pictures, and the sharing of files. Some possibilities include:

- teachers sharing announcements with students;

- students sharing information with teachers;

- sharing photos of work done in class;

- sharing audio files;

- correcting students’ texts by marking them up on WhatsApp.

In a survey, he found that many students were already using WhatsApp groups to support their studies, but without teachers present in those groups. Students’ perceptions of the use of WhatsApp for language learning (in a group including a teacher) were generally very positive; for example, they liked being able to clear up doubts immediately, engaging in collaborative and multimodal learning, and preserving traces of their learning. However, some found such a group too public, and much depends on the dynamics of groups; there is also a danger of message overload if students are offline for a while. Both teachers and students may feel under pressure to respond quickly at all times. In summary, despite some challenges, there is real potential in the use of WhatsApp for language learning, but its broader use will require a change of mindset on the part of teachers and students.

In their presentation, Does watching 360 degree virtual reality videos enhance Mandarin writing of Vietnamese students?, Thi Thu Tam Van and Yu-Ju Lan described a study in which students viewed photos (control group) or viewed 360 degree videos with Google Cardboard headsets (experimental group) before engaging in writing activities. Significant differences were found in all areas assessed (content, organisation, etc) and in overall performance; the authentic context provided by the 360 degree videos thus enhanced the level of students’ Mandarin writing. All students in the experimental group preferred using Google Cardboard compared to traditional methods in writing lessons.

In their paper, Discovering the effects of 3D immersive experience in enhancing oral communication of students in a college of medicine, Yi-Ju Ariel Wu and Yu-Ju Lan mentioned that 3D virtual worlds allow learners to immerse themselves fully and perform contextualised social interactions, while reducing their anxiety. The virtual world used was the Omni Immersion Vision Program from NTNU, Taiwan, and students engaged in a role-play about obesity (experimental group), while another group of students performed the role-play in a face-to-face classroom (control group). The experimental group created more scenes than the control group; used a wider range of objects; had richer communication, with the emergence of spontaneous talk; and their interaction was generally more fluid and imaginative. The experimental group said that using the virtual world reduced their fear of oral communication; made them more imaginative; and made oral communication more interesting.

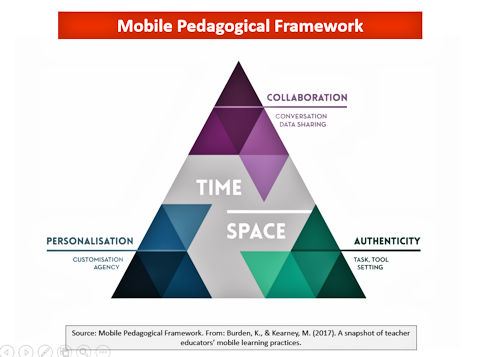

On the final day of the conference, I had the honour of chairing a session comprising six short papers covering topics such as online feedback, differences in MALL between countries, the use of WeChat for intercultural learning, and location-based games. I wrapped up this session with my own presentation, Personalisation, collaboration and authenticity in mobile language learning, where I outlined some of the key principles to consider when designing mobile language and literacy learning experiences for students.

Overall, the conference provided a good snapshot of current thinking about promoting language learning through smart technologies, an area whose potential is just beginning to unfold.