AILA World Congress

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

23-28 July 2017

Praia da Barra da Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2017. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

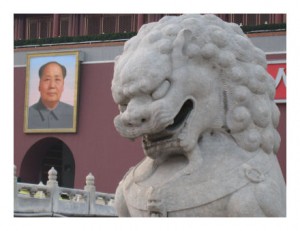

Having participated in the last two AILA World Congresses, in Beijing in 2011 and in Brisbane in 2014, I was delighted to be able to attend the 18th World Congress, taking place this time in the beautiful setting of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This year’s theme was “Innovations and Epistemological Challenges in Applied Linguistics”. As always, the conference brought together a large and diverse group of educators and researchers working in the broad field of applied linguistics, including many with an interest in digital and mobile learning, and digital literacies and identities. Papers ranged from the highly theoretical to the very applied, with some of the most interesting presentations actively seeking to build much-needed bridges between theory and practice.

In her presentation, E-portfolios: A tool for promoting learner autonomy?, Chung-Chien Karen Chang suggested that e-portfolios increase students’ motivation, promote different assessment criteria, encourage students to take charge of their learning, and stimulate their learning interests. Little (1991) looked at learner autonomy as a set of conditional freedoms: learners can determine their own objectives, define the content and process of their learning, select the desired methods and techniques, and monitor and evaluate their progress and achievements. Benson (1996) spoke of three interrelated levels of autonomy for language learners, involving the learning process, the resources, and the language. Benson and Voller (1997) emphasised four elements that help create a learning environment to cultivate learner autonomy, namely when learners can:

- determine what to learn (within the scope of what teachers want them to learn);

- acquire skills in self-directed learning;

- exercise a sense of responsibility;

- be given independent situations for further study.

Those who are intrinsically motivated are more self-regulated; in contrast, extrinsically motivated activities are less autonomous and more controlled. But either way, psychologically, students will be motivated to move forward.

The use of portfolios provides an alternative form of assessment. A portfolio can echo a process-oriented approach to writing. Within a multi-drafting process, students can check their own progress and develop a better understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. Portfolios offer multi-dimensional perspectives on student progress over time. The concept of e-portfolios is not yet fully fixed but includes the notion of collections of tools to perform operations with e-portfolio items, and collections of items for the purpose of demonstrating competence.

In a study with 40 sophomore and junior students, all students’ writing tasks were collected in e-portfolios constituting 75% of their grades. Many students agreed that writing helped improve their mastery of English, their critical thinking ability, their analytical skills, and their understanding of current events. They agreed that their instructor’s suggestions helped them improve their writing. Among the 40 students assessed on the LSRQ survey, the majority showed intrinsic motivation. Students indicated that the e-portfolios gave them a sense of freedom, and allowed them to challenge and ultimately compete against themselves.

Gamification emerged as a strong conference theme. In her paper, Action research on the influence of gamification on learning IELTS writing skills, Michelle Ocriciano indicated that the aim of gamification, which has been appropriated by education from the fields of business and marketing, is to increase participation and motivation. Key ‘soft gamification’ elements include points, leaderboards and immediate feedback; while these do not constitute full gamification, they can nevertheless have benefits. She conducted action research to investigate the question: how can gamification apply to a Moodle setting to influence IELTS writing skills? She found that introducing gamification elements into Moodle – using tools such as GameSalad, Quizlet, ClassTools, Kahoot! and Quizizz – not only increased motivation but also improved students’ spelling, broadened their vocabulary, and decreased the time they needed for writing, leading to increases in their IELTS writing scores. To some extent, students were learning about exam wiseness. The most unexpected aspect was that her feedback as the teacher increased in effectiveness, because students shared her individual feedback with peers through a class WhatsApp group. In time, students also began creating their own games.

The symposium Researching digital games in language learning and teaching, chaired by Hayo Reinders and Sachiko Nakamura, naturally also brought gaming and gamification to the fore in a series of presentations.

In their presentation, Merging the formal and the informal: Language learning and game design, Leena Kuure, Salme Kälkäjä and Marjukka Käsmä reported on a game design course taught in a Finnish high school. Students would recruit their friends onto the course, and some even repeated the course for fun. It was found that the freedom given to students did not necessarily mean that they took more responsibility, but rather this varied from student to student. Indeed, the teacher had a different role for each student, taking or giving varying degrees of responsibility. Students chose to use Finnish or English, depending on the target groups for the games they were designing.

The presenters concluded that in a language course like this, language is not so much the object of study (where it is something ‘foreign’ to oneself) but rather it is a tool (where it is part of oneself, and part of an expressive repertoire). Formal vs informal, they said, seems to be an artificial distinction. The teacher’s role shifts, with implications for assessment, and a requirement for the teacher to have knowledge of individual students’ needs. The choice of project should support language choice; this enables authentic learning situations and, through these, ‘language as a tool’ thinking.

In her presentation, The role of digital games in English education in Japan: Insights from teachers and students, Louise Ohashi began by referencing the gaming principles outlined in the work of James Paul Gee. She reported on a study of students’ experiences of and attitudes to using digital games for English study, as well as teachers’ experiences and attitudes. She surveyed 102 Japanese university students, and 113 teachers from high schools and universities. Students, she suggested, are not as interested as teachers in distinguishing ‘real’ games from gamified learning tools.

While 31% of students had played digital games in English in class over the previous 12 months, 50% had done so outside class, suggesting a clear trend towards out-of-class gaming. The games they reported playing covered the spectrum from general commercial games to dedicated language learning or educational games. Far more students than teachers thought games were valuable aids to study inside and outside class, as well as for self-study. Only 30% of students said that they knew of appropriate games for their English level, suggesting an area where teachers might be able to intervene more.

In fact, most Japanese classrooms are quite traditional learning spaces – often with blackboards and wooden desks, and no wifi – which do not lend themselves to gaming in class. While some teachers use games, many avoid them. One teacher surveyed thought students wouldn’t be interested in games; another worked at a school where students were not allowed to use computers or phones; another thought the school and parents would disapprove; others emphasised the importance of a focus on academic coursework rather than gaming; and still others objected to the idea that foreign teachers in Japan are supposed to entertain students. She concluded that most students were interested in playing games but most teachers did not introduce them, by choice or otherwise, possibly representing a missed opportunity.

In her presentation, Technology in support of heritage language learning, Sabine Little reported on an online questionnaire with 112 respondents, examining how families from heritage language backgrounds use technology to support heritage language literacy development for their primary school students. Two thirds of the families spoke two or more heritage languages in the home. She found that where there were children of different ages, use of the heritage language would often decrease for younger children.

Parents were gatekeepers of both technology use and choices of apps; but many parents didn’t have the technological understanding to identify apps or games their children might be interested in. Many thought that there were no apps in their language. Some worried about health issues; others worried about cost. There are both advantages and disadvantages in language learning games; many of these have no cultural content as they’re designed to work with more than one language. Similarly, authentic language apps have both advantages (e.g., they feel less ‘educational’) and disadvantages (e.g., they may be too linguistically difficult). Nevertheless, many parents agreed that their children were interested in games for language learning, and more broadly in learning the heritage language.

All in all, this is an incredibly complex field. How children engage with heritage language resources is linked to their sense of identity as pluricultural individuals. Many parents are struggling with the ‘bad technology’/’good language learning opportunity’ dichotomy. In general, parents felt less confident about supporting heritage language literacy development through technology than through books.

In my own presentation, Designing for situated language and literacy: Learning through mobile augmented reality games and trails, I discussed the places where online gaming meets the offline world. I focused on mobile AR gamified learning trails, drawing on examples of recent, significant, informative projects from Singapore, Indonesia and Hong Kong. The aim of the presentation was to whet the appetite of the audience for the possibilities that emerge when we bring together online gaming, mobility, augmented reality, and language learning.

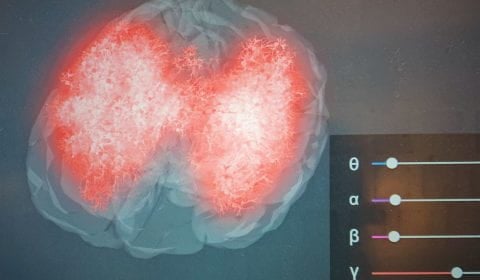

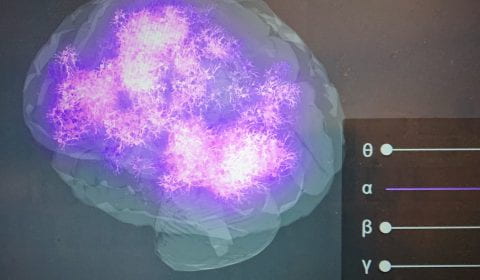

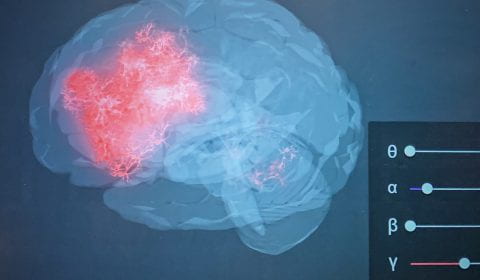

AR and big data were also important conference themes. In his paper, The internet of things: Implications for learning beyond the classroom, Hayo Reinders suggested that algorithmic approaches like Bayesian Networks, Nonnegative Matrix Factorization, Native Forests, and Association Rule Mining are beginning to help us make sense of vast amounts of data. Although they are not familiar to most of today’s teachers, they will be very familiar to future teachers. We are gradually moving from reactive to proactive systems, which can predict future problems in areas ranging from health to education. Current education is completely reactive; we wait for students to do poorly or fail before we intervene. Soon we will have the opportunity to change to predictive systems. All of this is enabled by the underpinning technologies becoming cheaper, smaller and more accessible.

He spoke about three key areas of mobility, ubiquity, and augmentation. Drawing on Klopfer et al (2002), he listed five characteristics of mobile technologies which could be turned into affordances for learning: portability; social interactivity; context sensitivity; connectivity; and individuality. These open up a spectrum of possibilities, he indicated, where the teacher’s responsibility is to push educational experiences towards the right-hand side of each pair:

- Disorganised – Distributed

- Unfocused – Collaborative

- Inappropriate – Situated

- Unmanageable – Networked

- Misguided – Autonomous

Augmentation is about overlaying digital data, ranging from information to comments and opinions, on real-world settings. Users can add their own information to any physical environment. Such technologies allow learning to be removed from the physical constraints of the classroom.

With regard to ubiquity, when everything is connected to everything else, there is potentially an enormous amount of information generated. He described a wristband that records everything you do, 24/7, and forgets it after two minutes, unless you tap it twice to save what has been recorded and have it sent to your phone. Students can use this, for example, to save instances of key words or grammatical structures they encounter in everyday life. Characteristics of ubiquity that have educational implications include the following:

- Permanency can allow always-on learning;

- Accessibility can allow experiential learning;

- Immediacy can allow incidental learning;

- Interactivity can allow socially situated learning.

He went on to outline some key affordances of new technologies, linked to the internet of things, for learning:

- Authentication for attendance when students enter the classroom;

- Early identification and targeted support;

- Adaptive and personalised learning;

- Proactive and predictive rather than reactive management of learning;

- Continuous learning experiences;

- Informalisation;

- Empowerment of students through access to their own data.

He wrapped up by talking about the Vital Project that gives students visualisation tools and analytics to monitor online language learning. Research has found that students like having access to this information, and having control over what information they see, and when. They want clear indications of progress, early alerts and recommendations for improvement. Cultural differences have also been uncovered in terms of the desire for comparison data; the Chinese students wanted to know how they were doing compared with the rest of the class and past cohorts, whereas non-Chinese did not.

There are many questions remaining about how we can best make use of this data, but it is already coming in a torrent. As educators, we need to think carefully about what data we are collecting, and what we can do with it. It is only us, not computer scientists, who can make the relevant pedagogical decisions.

In his paper, Theory ensembles in computer-assisted language learning research and practice, Phil Hubbard indicated that the concept of theory was formerly quite rigidly defined, and involved the notion of offering a full explanation for a phenomenon. It has now become a very fluid concept. Theory in CALL, he suggested, means the set of perspectives, models, frameworks, orientations, approaches, and specific theories that:

- offer generalisations and insights to account for or provide greater understanding of phenomena related to the use of digital technology in the pursuit of language learning objectives;

- ground and sustain relevant research agendas;

- inform effective CALL design and teaching practice.

He presented a typology of theory use in CALL:

- Atheoretical CALL: research and practice with no explicit theory stated (though there may be an implicit theory);

- Theory borrowing: using a theory from SLA, etc, without change;

- Theory instantiation: taking a general theory with a place for technology and/or SLA into consideration (e.g., activity theory);

- Theory adaptation: changing one or more elements of a theory from SLA, etc, in anticipation of or in response to the impact of the technology;

- Theory ensemble: combining multiple theoretical entities in a single study to capture a wider range of perspectives;

- Theory synthesis: creating a new theory by integrating parts of existing ones;

- Theory construction: creating a new theory specifically for some sub-domain of CALL;

- Theory refinement: cycles of theory adjustment based on accumulated research findings.

He went on to provide some examples of research approaches based on theory ensembles. We’re just getting started in this area, and it needs further study and refinement. Theory ensembles seem to occur especially in CALL studies involving gaming, multimodality, and data-driven learning. Theory ensembles may be ‘layered’, with a broad theory providing an overarching approach of orientation, and complementary narrower theoretical entities providing focus. Similarly, members of a theory ensemble have different functions and therefore different weights in the overall picture. Some can be more central than others. A distinction might be made, he suggested, between one-time ensembles assembled for a given problem and context, and more stable ones that could lead to full theory syntheses. Finally, each ensemble member should have a clear function, and together they should lead to a richer and more informative analysis; researchers and designers should clearly justify the membership of ensembles, and reviewers should see that they do so.

Intercultural issues surfaced in many papers, perhaps most notably in the symposium Felt presence, imagined presence, hyper-presence in online intercultural encounters: Case studies and implications, chaired by Rick Kern and Christine Develotte. It was suggested by Rick Kern that people often imagine online communication is immediate, but in fact it is heavily technologically mediated, which has major implications for the nature of communication.

In their paper, Multimodality and social presence in an intercultural exchange setting, Meei-Ling Liaw and Paige Ware indicated that there is a lot of research on multimodality, communication differences, social presence and intercultural communication, but it is inconclusive and sometimes even contradictory. They drew on social presence theory, which postulates that a critical factor in the viability of a communication medium is the degree of social presence it affords.

They reported on a project involving 12 pre-service and 3 in-service teachers in Taiwan, along with 15 undergraduate Education majors in the USA. Participants were asked to use VoiceThread, which allows text, audio and video communication, and combinations of these. Communication was in English, and was asynchronous because of the time difference. It was found that the US students used video exclusively, but the Taiwanese used a mixture of modalities (text, audio and video). The US students found video easy to use, but some Taiwanese students worried about their oral skills and felt they could organise their thoughts better in text; however, other Taiwanese students wanted to practise their oral English. All partnerships involved a similar volume of words produced, perhaps indicating that the groups were mirroring each other. In terms of the types of questions posed, the Taiwanese asked far more questions about opinions; the American students were more cautious about asking such questions, and also knew little about Taiwan and so asked more factual questions. Overall, irrespective of the modality employed, the two groups of intercultural telecollaborative partners felt a strong sense of membership and thought that they had achieved a high quality of learning because of the online partnership.

As regards the pedagogical implications, students need to be exposed to the range of features available in order to maximise the affordances of all the multimodal choices. In addition to helping students consider how they convey a sense of social presence through the words and topics they choose, instructors need to attend to how social presence is intentionally or unintentionally communicated in the choice of modality. The issue of modality choice is also intimately connected to the power dynamic that can emerge when telecollaborative partnerships take place as monolingual exchanges.

In their paper, Conceptualizing participatory literacy: New approaches to sustaining co-presence in social and situated learning communities, Mirjam Hauck, Sylvie Warnecke and Muge Satar argued that teacher preparation needs to address technological and pedagogical issues, as well as sociopolitical and ecological embeddedness. Both participatory literacy and social presence are essential, and require multimodal competence. The challenge for educators in social networking environments is threefold: becoming multimodally aware and able to first establish their own social presence, and then successfully participating in the collaborative creation and sharing of knowledge, so that they are well-equipped to model such an ability and participatory skills for their students.

Digital literacy/multiliteracy in general, and participatory literacy in particular, is reflected in language learners’ ability to comfortably alternate in their roles as semiotic responders and semiotic initiators, and the degree to which they can make informed use of a variety of semiotic resources. The takeaway from this is that being multimodally able and as a result a skilled semiotic initiator and responder, and being able to establish social presence and participate online, is a precondition for computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) of languages and cultures.

They reported on a study with 36 pre-service English teachers learning to establish social presence through web 2.0 tools. Amongst other things, students were asked to reflect on their social presence in the form of a Glogster poster referring to Gilly Salmon’s animal metaphors for online participation (see p.12); students showed awareness that social presence is transient and emergent.

They concluded that educators need to be able to illustrate and model for their students the interdependence between being multimodally competent as reflected in informed semiotic activity, and the ability to establish social presence and display participatory literacy skills. Tasks like those in the training programme presented here, triggering ongoing reflection on the relevance of “symbolic competence” (Kramsch, 2006), social presence and participatory literacy, need to become part of CSCL-based teacher education.

In his presentation, Seeing and hearing apart: The dilemmas and possibilities of intersubjectivity in shared language classrooms, David Malinowski spoke about the use of high-definition video conferencing for synchronous class sessions in languages with small enrolments, working across US institutions.

It was found that technology presents an initial disruption which is overcome early in the semester, and does not prevent social cohesion. There is the ability to co-ordinate perspective-taking, dialogue, and actions with activity type and participation format. Synchronised performance, play and ritual may deserve special attention in addition to sequentially oriented events. History is made in the moment: durable learner identities inflect moment to moment, and there are variable engagements through and with technology. There are ongoing questions about parity of the educational experience in ‘sending’ and ‘receiving’ classrooms. Finally, there is a need to develop further tools to mediate the life-worlds of distance language learners across varying timescales.

Christo Redentor, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2017. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

There were many presentations that ranged well beyond CALL, and to some extent beyond educational technologies, but which nevertheless had considerable contextual relevance for those working in CALL and MALL, and e-learning and mobile learning more broadly.

The symposium Innovations and challenges in digital language practices and critical language/media awareness for the digital age, chaired by Jannis Androutsopoulos, consisted of a series of papers on the nature of digital communication, covering themes such as the link between language use and language ideology; multimodality; and the use of algorithms. One key question, it was suggested in the introduction, is how linguistic research might speak to language education.

In their presentation, Critical media awareness in a digital age, Caroline Tagg and Philipp Seargeant stated that people’s critical awareness develops fluidly and dynamically over time in response to experiences online. They introduced the concept of context design, which suggests that context is collaboratively co-constructed in interaction through linguistic choices. The concept draws on the well-known notion of context collapse, but suggests that offline contexts cannot simply move online and collapse; rather, contexts are always actively constructed, designed and redesigned. Context design incorporates the following elements:

- Participants

- Online media ideologies

- Site affordances

- Text type

- Identification processes

- Norms of communication

- Goals

They reported on a study entitled Creating Facebook (2014-2016). Their interviews revealed complex understandings of Facebook as a communicative space and the importance of people’s ideas about social relationships. These understandings shaped behaviour in often unexpected ways, in processes that can be conceptualised as context design. They concluded that the role of people’s evolving language/media awareness in shaping online experiences needs to be taken into account by researchers wishing to effectively build a critical awareness for the digital age.

In her paper, Why are you texting me? Emergent communicative practices in spontaneous digital interactions, Maria Grazia Sindoni suggested that multimodality is a reaction against language-driven approaches that sideline resources other than language. However, language as a resource has been sidelined in mainstream multimodality research. Yet language still needs to be studied, but on a par with other semiotic resources.

In a study of reasons for mode-switching in online video conversations, she indicated that the technical possibility of doing something does not equate with the semiotic choice of doing so. In the case of communication between couples, she noted a pattern where intimate communications often involve a switch from speech to text. She also presented a case where written language was used to reinforce spoken language; written conventions can thus be creatively resemiotised.

There are several layers of meaning-making present in such examples: creative communicative functions in language use; the interplay of semiotic resources other than language that are co-deployed by users to adapt to web-mediated environments (e.g., the impossibility of perfectly reciprocating gaze, em-/disembodied interaction, staged proxemics, etc); different technical affordances (e.g., laptop vs smartphone); and different communicative purposes and degrees of socio-semiotic and intercultural awareness. She concluded with a critical agenda for research on web-mediated interaction, involving:

- recognising the different levels (above) and their interplay;

- encouraging critical awareness of video-specific patterns in syllabus design and teacher training;

- promoting understanding of what can hinder or facilitate interaction (also in an intercultural light);

- technical adaptivity vs semiotic awareness.

In their paper, Digital punctuation: Practices, reflexivity and enregistrement in the case of <.>, Jannis Androutsopoulos and Florian Busch referred to David Crystal’s view that in online communication the period has almost become an emoticon, one which is used to show irony or even aggression. They went on to say that the use of punctuation in contemporary online communication goes far beyond the syntactic meanings of traditional punctuation; punctuation and emoticons have become semiotic resources and work as contextualisation cues that index how a communication is to be understood. There is currently widespread media discussion of the use of punctuation, including specifically about the disappearance of the period. They distanced themselves from Crystal’s view of “linguistic free love” and the breaking of rules in the use of punctuation on the internet, suggesting that there are clear patterns emerging.

Reporting on a study of the use of punctuation in WhatsApp conversations by German students, they found relatively low use of the period. This suggests that periods are largely being omitted, and when they do occur, they generally do so within messages where they fulfil a syntactic function. They are very rare at the end of messages, where they may fulfil a semiotic function. For example, periods may be used for register switching, indicating a change to a more formal register; or to indicate unwillingness to participate in further conversation. Use of periods by one user may even be commented on by other users in a case of metapragmatic reflexivity. It was commented by interviewees that the use of periods at the end of messages is strange and annoying in the context of informal digital writing, especially as the WhatsApp bubbles already indicate the end of messages. One interviewee commented that the use of punctuation in general, and final periods in particular, can express annoyance and make a message appear harsher, signalling the bad mood of the writer. The presenters concluded that digital punctuation offers evidence of ongoing elaboration of new registers of writing in the early digital age.

In his presentation, The text is reading you: Language teaching in the age of the algorithm, Rodney Jones suggested that we should begin talking to students about digital texts by looking at simple examples like progress bars; as he explained, these do not represent the actual progress of software installation but are underpinned by an algorithm that is designed to be psychologically satisfying, thus revealing the disparity between the performative and the performance.

An interesting way to view algorithms is through the lens of performance. He reported on a study where his students identified and analysed the algorithms they encounter in their daily lives. He highlighted a number of key themes in our beliefs about algorithms:

- Algorithmic Agency: ‘We sometimes believe the algorithm is like a person’; we may negotiate with the algorithm, changing our behaviour to alter the output of the algorithm

- Algorithmic Authority (a term by Clay Shirky, who defines it as our tendency to believe algorithms more than people): ‘We sometimes believe that the algorithm is smarter than us’

- Algorithm as Adversary: ‘We believe the algorithm is something we can cheat or hack’; this is seen in student strategies for altering TurnItIn scores, or in cases where people play off one dating app against another

- Algorithm as Conversational Resource: ‘We think we can use algorithms to talk to others’; this can be seen for example when people tailor Spotify feeds to impress others and create common conversational interests

- Algorithm as Audience: ‘We believe that algorithms are watching us’; this is the sense that we are performing for our algorithms, such as when students consider TurnItIn as their primary audience

- Algorithm as Oracle: ‘We sometimes believe algorithms are magic’; this is seeing algorithms as fortune tellers or as able to reveal hidden truths, involving a kind of magical thinking

The real pleasure we find in algorithms is the sense that they really know us, but there is a lack of critical perspective and an overall capitulation to the logic of the algorithm, which is all about the monetisation of our data. There is no way we can really understand algorithms, but we can think critically about the role they play in our lives. He concluded with a quote from Ben Ratliff, a music critic at The New York Times: “Now the listener’s range of access is vast, and you, the listener, hold the power. But only if you listen better than you are being listened to”.

In her presentation, From hip-hop pedagogies to digital media pedagogies: Thinking about the cultural politics of communication, Ana Deumert discussed the privileging of face-to-face conversation in contemporary culture; a long conversation at a dinner party would be seen as a success, but a long conversation on social media would be seen as harmful, unhealthy, a sign of addiction, or at the very least a waste of time. Similarly, it is popularly believed that spending a whole day reading a book is good; but reading online for a whole day is seen as bad.

She asked what we can learn from critical hip-hop studies, which challenge discourses of school versus non-school learning. She also referred to Freire, who considered that schooling should establish a connection between learning in school and learning in everyday life outside school. New media, she noted, have offered opportunities to minorities, the disabled, and speakers of minority languages. If language is seen as free and creative, then it is possible to break out of current discourse structures. Like hip-hop pedagogies, new media pedagogies allow us to bring new perspectives into the classroom, and to address the tension between institutional and vernacular communicative norms through minoritised linguistic forms and resources. She went on to speak of Kenneth Goldsmith’s course Wasting Time on the Internet at the University of Pennsylvania (which led to Goldsmith’s book on the topic), where he sought to help people think differently about what is happening culturally when we ‘waste’ time online. However, despite Goldsmith’s comments to the contrary, she argued that online practices always have a political dimension. She concluded by suggesting that we need to rethink our ideologies of language and communication; to consider the semiotics and aesthetics of the digital; and to look at the interplay of power, practice and activism online.

Given the current global sociopolitical climate, it was perhaps unsurprising that the conference also featured a very timely strand on superdiversity. The symposium Innovations and challenges in language and superdiversity, chaired by Miguel Pérez-Milans, highlighted the important intersections between language, mobility, technology, and the ‘diversification of diversity’ that characterises increasing areas of contemporary life.

In his presentation, Engaging superdiversity – An empirical examination of its implications for language and identity, Massimiliano Spotti stressed the importance of superdiversity, but indicated that it is not a flawless concept. Since its original use in the UK context, the term has been taken up in many disciplines and used in different ways. Some have argued that it is theoretically empty (but maybe it is conceptually open?); that it is a banal revisitation of complexity theory (but their objects of enquiry differ profoundly); that it is naïve about inequality (but stratification and ethnocentric categories are heavily challenged in much of the superdiversity literature); that it lacks a historical perspective (he agreed with this); that it is neoliberal (the subject it produces is a subject that fits the neoliberal emphasis on lifelong learning); and that it is Eurocentric, racist and essentialist.

He went on to report on research he has been conducting in an asylum centre. Such an asylum seeking centre, he said, is effectively ‘the waiting room of globalisation’. Its guests are mobile people, and often people with a mobile. They may be long-term, short-term, transitory, high-skilled, low-skilled, highly educated, low-educated, and may be on complex trajectories. They are subject to high integration pressure from the institution. They have high insertional power in the marginal economies of society. Their sociolinguistic, ethnic, religious and educational backgrounds are not presupposable.

In his paper, ‘Sociolinguistic superdiversity’: Paradigm in search of explanation, or explanation in search of paradigm?, Stephen May went back to Vertovec’s 2007 work, focusing on the changing nature of migration in the UK; ethnicity was too limiting a focus to capture the differences of migrants, with many other variables needing to be taken into account. Vertovec was probably unaware, May suggested, of the degree of uptake the term ‘superdiversity’ would see across disciplines.

May spoke of his own use of the term ‘multilingual turn’, and referred to Blommaert’s emphasis on three key aspects of superdiversity, namely mobility, complexity and unpredictability. The new emphasis on superdiversity is broadly to be welcomed, he suggested, but there are limitations. He outlined four of these:

- the unreflexive ethnocentrism of western sociolinguistics and its recent rediscovery of multilingualism as a central focus; this is linked to a ‘presentist’ view of multilingualism, with a lack of historical focus

- the almost exclusive focus on multilingualism in urban contexts, constituting a kind of ‘metronormativity’ compared to ‘ossified’ rural/indigenous ‘languages’, with the former seen as contemporary and progressive, thus reinforcing the urban/rural divide

- a privileging of individual linguistic agency over ongoing linguistic ‘hierarchies of prestige’ (Liddicoat, 2013)

- an ongoing emphasising of parole over langue; this is still a dichotomy, albeit an inverted one, and pays insufficient attention to access to standard language practices; it is not clear how we might harness different repertoires within institutional educational practices

In response to such concerns, Blommaert (2015) has spoken about paradigmatic superdiversity, which allows us not only to focus on contemporary phenomena, but to revisit older data to see it in a new light. There are both epistemological and methodological implications, he went on to say. There is a danger, however, in a new orthodoxy which goes from ignoring multilingualism to fetishising or co-opting it. We also need to attend to our own positionality and the power dynamics involved in who is defining the field. We need to avoid superdiversity becoming a new (northern) hegemony.

In her paper, Superdiversity as reality and ideology, Ryuko Kubota echoed the comments of the previous speakers on human mobility, social complexity, and unpredictability, all of which are linked to linguistic variability. She suggested that superdiversity can be seen both as an embodiment of reality as well as an ideology.

Superdiversity, she said, signifies a multi/plural turn in applied linguistics. Criticisms include the fact that superdiversity is nothing extraordinary; many communities maintain homogeneity; linguistic boundaries may not be dismantled if analysis relies on existing linguistic units and concepts; and it may be a western-based construct with an elitist undertone. As such, superdiversity is an ideological construct. In neoliberal capitalism there is now a pushback against diversity, as seen in nationalism, protectionism and xenophobia. But there is also a complicity of superdiversity with neoliberal multiculturalism, which values diversity, flexibility and fluidity. Neoliberal workers’ experiences may be superdiverse or not so superdiverse; over and against linguistic diversity, there is a demand for English as an international language, courses in English, and monolingual approaches.

One emerging question is: do neoliberal corporate transnational workers engage in multilingual practices or rely solely on English as an international language? In a study of language choice in the workplace with Japanese and Korean transnational workers in manufacturing companies in non-English dominant countries, it was found that nearly all workers exhibited multilingual and multicultural consciousness. There was a valorisation of both English and a language mix in superdiverse contexts, as well as an understanding of the need to deal with different cultural practices. That said, most workers emphasised that overall, English is the most important language for business. Superdiversity may be a site where existing linguistic, cultural and other hierarchies are redefined and reinforced. Superdiversity in corporate settings exhibits contradictory ideas and trends.

In terms of neoliberal ideology, superdiversity, and the educational institution, she mentioned expectations such as the need to produce original research at a sustained pace; to conform to the conventional way of expressing ideas in academic discourse; and to submit to conventional assessment linked to neoliberal accountability. Consequences include a proliferation of trendy terms and publications; and little room for linguistic complexity, flexibility, and unpredictability. She went on to talk about who benefits from discussing superdiversity. Applied linguistics scholars are embedded in unequal relations of power. As theoretical concepts become fetishised, the theory serves mainly the interests of those who employ it, as noted by Anyon (1994). It is necessary for us to critically reflect, she said, on whether the popularity of superdiversity represents yet another example of concept fetishism.

In conclusion, she suggested that superdiversity should not merely be celebrated without taking into consideration historical continuity, socioeconomic inequalities created by global capitalism, and the enduring ideology of linguistic normativism. Research on superdiversity also requires close attention to the sociopolitical trend of increasing xenophobia, racism, and assimilationism. Ethically committed scholars, she said, must recognise the ideological nature of trendy concepts such as superdiversity, and explore ways in which sociolinguistic inquiries can actually help narrow racial, linguistic, economic and cultural gaps.

Rio de Janeiro viewed from Pão de Açúcar. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2017. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

AILA 2017 wrapped up after a long and intensive week, with conversations to be continued online and offline until, three years from now, AILA 2020 takes place in Groningen in the Netherlands.