WUN Understanding Global Digital Cultures Conference

Hong Kong

25-26 April, 2015

The WUN (Worldwide Universities Network) Understanding Global Digital Cultures Conference took place on 25-26 April at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, bringing together speakers from the WUN network of universities around the world. The local focus on Hong Kong and Chinese digital culture provided a fascinating counterpoint to a range of local and global presentations.

In his opening plenary, Imagining the internet: The politics and poetics of China’s cyberspace, Hu Yong argued that the Chinese internet is a space where the government is not able to interfere completely; its decentralisation and partial anonymity have allowed it to become an arena for citizens to exchange ideas and opinions. The people are increasingly trying to hold the government accountable according to the rights given them in the constitution. The internet has become a stand-in for face-to-face gatherings.

The government is now attempting to exert further control over the freedom of the internet, with a ‘control first, develop later’ strategy. The government considers people with different opinions as imaginary enemies. There have been new laws created and more arrests of verified users. Sometimes local government is sacrificed for the sake of the central government.

In fact, censorship is an intrinsic characteristic of the Chinese internet, as it is in all areas of Chinese life. It is not mentioned officially, but in private people will joke about censorship. The citizens have thus turned the internet into a platform for sarcastic spoofing of the authorities – this can be seen as the ‘poetics’ of Chinese digital culture, much of it based on a play on words and sounds (see image below). Those who lack power have been empowered, and those with power have lost it; the more you try to crack down on spoofing, the more it proliferates. But at the same time, this spoofing operates within a culture of fear. The use of this spoofing and the metaphors that underpin it have also reinforced the doublethink of Chinese culture, which is a culture of public lies and private truths.

The Chinese internet is not monolithic but rather the site of conflict between different levels of government, various departments, and between the impulse to block and the impulse to monitor citizens.

In his presentation, The urban/digital nexus: Participation, belonging and social media in Auckland, New Zealand, Jay Marlowe spoke about superdiversity as a diversification of diversity, which requires an analysis across different kinds of social differentiation. Participants in the reported Auckland study of migrants said that the digital environment augmented their existing social relationships and made new relationships possible. Different digital platforms provided different ‘textures’, with Skype for example allowing synchronous contact, and messaging apps being used in local spaces. Participants reported a gradual normalisation of ‘platformed sociality’, with considerable pressure to participate online. There was also a sense that real-life experiences need to be presented and demonstrated on social media platforms.

Overall, there is a transition from a participatory culture to a culture of connectivity; existing networks are reinforced but relationships may have migrated from face-to-face to online interaction. Greater connectivity does not necessarily mean greater connection – but it can. The landscape of access also matters; digital illiteracy becomes a new kind of poverty. It was clear that the participants were digital learners and digitally distracted at the same time, which has implications for education.

In her presentation, Material-semiotic particularity and the ‘broken’ smart city, Rolien Hoyng used the example of Istanbul and the Gezi Park protests of 2013 to contrast the development of smart cities through digital technologies and the facilitation of protests through those same technologies. There is a struggle over data ownership between the state and protesters.

In the presentation Everydaymaking through Facebook: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, UK and USA, Ariadne Vromen spoke about how young people use Facebook to engage in politics. She spoke of Henrik Bang’s concept of ‘everydaymaking’, suggesting that political engagement is increasingly local, DIY, ad hoc, fun, issues-driven and based on social change, but not necessarily underpinned by traditional conceptions of such change. A study was conducted to compare young people’s usage of Facebook for political engagement in Australia, the UK and the USA. In all three countries, the greatest predictor of using Facebook to engage with politics was that young people were already engaged with politics. Everdaymaking norms were important, but pre-existing engagement was more important.

When asked about discussing politics on Facebook, most young people said they would avoid it in order to avoid conflict. In particular, they were afraid of disagreement, offending someone, or having the facts wrong. On the other hand, a small group of young people were more positive about their political engagement on Facebook. Often, they were comfortable with likes and shares, and obtaining information through political pages.

Overall, social media erodes dutiful citizen relationships with politics, but young people are wary of politics entering their social space. It is interesting to note that young people associate politics with (digital) conflict, while the like button on Facebook creates consensus.

Referring to the same research project, Brian Loader gave a presentation entitled Performing for the young networked citizen? Celebrity politics, social networking and the political engagement of young people, in which he addressed the notion of ‘celebrity politics’, where politicians use social media. There is an increase in both celebrity politicians and political celebrities, and an overall personalisation of politics.

When asked what they thought about politicians using Facebook and Twitter, a minority of young people were negative, but most were open to it, though not uncritically so. It was very clear again, as in the preceding talk, that young people do not like aggression and negativity online. Generally the young people were also positive about celebrities using social media to raise important social issues, though there were concerns that they might lack expertise or unduly influence young fans.

Overall, social media will continue to be an important communication space for democratic politics. Politicians will need to share this space with celebrities who play an important role in opening up discussions. Social media also facilitate emotional evaluation of politicians, so they may need to show more of their human side. There would seem to be an indication that political use of social media is more inclusive for young people from lower SES (socio-economic status) backgrounds.

In her presentation, Affective space, affective politics: Understanding political emotion in cyber China, Yi Liu suggested that political participation in cyber China is highly charged with emotions, especially negative ones. Digital politics in China are extremely ambiguous – people have tactics to cope with constraints; there is a positive influence of commercial forces; there are conflicts within the state authority; and there is politicised but marginalised overseas deliberation alongside a vibrant but constrained local discussion. She is undertaking a study to investigate emotional discourse within the Tianya BBS, Kaidi BBS, and Quiangguo BBS.

On the second morning of the conference, there was a fascinating set of papers about Occupy Central and the Umbrella Movement, entitled Social media in Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. It was a privilege for the international audience to hear local voices on the events of last year.

In the paper, Social media and mode of participation in a large-scale collective action: The case of the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, Francis Lee showed that the number of protests in Hong Kong has been increasing annually, with protests having become somewhat normalised and therefore somewhat less effective. The Occupy Central movement was meant to be a short, disciplined intervention in this context. The Umbrella Movement that emerged in the wake of the police using tear gas against the Occupy Central movement was in many ways a networked movement which made extensive use of digital media, including the changing of social media profiles, dispelling rumours, etc. There were various ways of participating, with some 20% of Hong Kong adults saying they went to an occupied area to support the movement. He reported on an interview-based study of protesters, which revealed both their real-world activities and their digital media activities.

Some of the digital activities were expressive in nature and mainly involved showing support, but others were an important part of the dynamics of the movement in dispelling rumours and so on. Overall, the digital media activities were significant in the Umbrella Movement for extending participation from the physical urban space of the occupied areas to cyberspace. Mobile communication was particularly related to participation in occupied areas. Individuals could thus be selectively engaged in digital media activities and construct their own distinctive forms of participation in the movement.

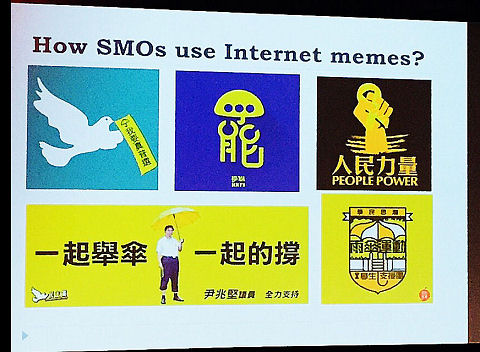

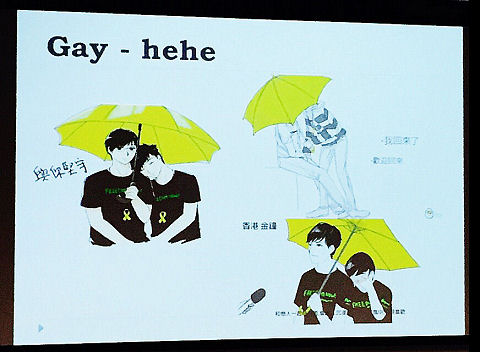

In their paper, Internet memes in social movement: How the mobilisation effects are facilitated and constrained in Hong Kong Umbrella Movement, Chan Ngai Keung and Su Chris Chao spoke of the three key internet memes associated with the Umbrella Movement: the yellow ribbon (mostly used as a logo, e.g., as a profile picture on Facebook) , the yellow umbrella (suggestive of self-protection), and the slogan ‘I want real universal suffrage’ (which co-occurred with Lion Rock, and was widely reported by the mass media). They reported on a study where they investigated the use of these memes on Facebook (see image). They showed numerous examples of remixes of the three key images with pictures of famous characters, superheros, artists and politicians, and even gay-themed remixes (see image). Eventually there was a commodification of the images, which were available for purchase on clothing, umbrellas, and so on.

Overall, the memes primarily served the purpose of political persuasion and action. The commodification of internet memes does not necessarily serve political purposes. While Facebook spread these memes, it also constrained them in some ways, because on Facebook it is difficult to use hashtags or search engines to find related materials. Internet memes are often related to humour, but not necessarily – here they were about positive mobilisation.

In her paper, ‘It happens here and now’: Digital media documentation during the Umbrella Movement, Lisa Leung commented on the way in which Hong Kong people found their agency at the time of the tear gassing during Occupy Central. She noted the key role played by social media, not only in facilitating the protests, but crucially also in archiving and remembering. Facebook, she suggested, also functions as a space within which Hong Kong people can imagine a better future.

In the last of the papers in this session, Education, media exposure and political position: Mainlanders in the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement, Zhao Mengyang noted that the Hong Kong protests had a spillover effect on the rest of the world. In Mainland China, some were supportive, and others were critical and saw the Hong Kong people as spoiled and disorderly. It was suggested that two crucial factors in the Mainlanders’ acceptance of the Umbrella Movement could be media exposure and education.

She reported on a Qualtrics survey of Mainlanders about the Hong Kong protests, which produced 2,184 valid responses. She found that: older people, males and non-CCP members were more supportive of the protests; more frequent use of newspapers, TV news and news websites was correlated with a lower level of support; more frequent use of social networking sites was correlated with a higher level of support; higher use of foreign media was correlated with a higher level of support; and higher education and full-time study were correlated with a lower level of support.

A few key suggestions emerged. Although overall internet censorship in China is strong, domestic social networking platforms might still allow moderate occurrence of alternative views. Full-time students might be more exposed to state discourse, and Chinese universities are part of the Chinese political apparatus. All in all, the chance of a spillover mobilisation effect might be slim in China.

In a later session entitled Behind the Great Firewall, several papers addressed the nature of the Chinese internet.

In their paper, Citizen attitudes toward China’s maritime territorial disputes: Traditional media and internet usage as distinctive conduits of political views in China, David Denemark and Andrew Chubb reported on a study of Chinese citizens’ attitudes to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands dispute, based on a survey of 1,413 adults conducted in five Chinese cities. Television was overwhelmingly the dominant source of information about the maritime disputes, with more than 90% of respondents obtaining information here; print media were used by around 2/3 of respondents; and 46% got their information via online sources; there was also crosscutting influence between different channels. The online sources were used by the young, the middle class, and the university-educated (but many of the last group also used print). This shows that the use of media is not monolithic. Overall, the two traditional media, newspapers and TV, have very similar effects on citizens’ political attitudes; the internet attracts a different audience, but it’s not enough to wash out the effects of the traditional media, which nearly everyone is using to some degree.

In his paper, The predicament of Chinese Internet culture, Gabriele De Seta noted that when we go beyond the anglophone media, it becomes much more complex to analyse the media landscape. He noted that Chinese memes such as the Grass Mud Horse can be interpreted in different ways. Online culture (网络文化) in China is very complex because it has so many layers. He showed that an anglophone concept like ‘trolling’ has many different translations and implications on the Chinese internet, and is highly segmented and differentiated, with differences found between China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. He went on to discuss a study of the Momo dating app, which was found to be used not mainly for dating, but for chatting with other bored people in the same locality, to set up a kind of online diary, or to explore the affordances of the app for self-expression. It is important, therefore, to examine situated media practices: complicating ‘cultures’ behind ‘firewalls’, downsizing the internet into platforms, services and devices; and accounting for content as small data.

On the second afternoon, a series of related papers were grouped together in a session entitled Storytelling individuals and communities.

In her paper, Automated diaries and quantified selves, Jill Walker Rettberg talked about the history of qualitative and quantitative self-representation and how it led up to the present era of self-recording through digital technologies, such as the lifelogging enabled by a device like Narrative Clip. She mentioned the term ‘numerical narratives’, used by Robert Simanowski to describe the sequencing of quantified data to tell the story of our lives. She concluded with a comment about ‘dataism’, the widespread belief in the objective quantification and tracking of human data as being potentially more reliable than our own memories of our life stories.

In our own presentation, Seeking common ground: Experiences of a Chinese-Australian digital storytelling project, Grace Oakley, Xi Bei Xiong and I talked about our experiences of running a digital storytelling project funded by the Australia-China Council from 2013-2014, where middle school students in China and Australia created and exchanged digital multimedia stories about their everyday lives. The key lessons we learned were all associated with the core theme of the need to seek common ground between the wishes and expectations of the project partners. This theme applied in the practical areas of motivation to participate, organisation, and technology (where our experiences reflected the commentary in the telecollaboration literature); and in the cultural areas of educational culture and pedagogy (where our experiences echoed the commentary in the anthropological and sociological literature about cultural differences).

In her presentation, ‘Are you being heard?’ The challenges of listening in the digital age, Tanja Dreher pointed out, with reference to the work of Jean Burgess, that it when it comes to democratic media participation, it doesn’t just matter who gets to speak, it matters who is heard. There is a lot to celebrate around affordances for voice on the internet, but this doesn’t mean that those voices are being heard. She spoke about the ‘listening turn’, where we are beginning to pay more attention to listening and not just speaking. Listening can be active and a form of agency. Key challenges include: overload and filtering (what is filtered in and out, and how does curation occur?); finding audiences; listening as participation (lurking in the sense of a listening presence is required to allow voices to manifest, as noted by Kate Crawford); and architectures of listening (how institutions and organisations might open up to listening more). We may need to think more about listening responsibilities: the proliferation of possibilities for voice online brings new responsibilities for listening.

In the closing plenary, Unstoppable networking: Social and political activism in the digital age, Lee Rainie described the Pew Research Center as a ‘fact tank’ which has no official position on the technological trends on which it reports. He outlined his two main points at the outset: Networked individuals using networked information create networked organisations and movements; and networking is unstoppable because people will always have problems they want to solve, and there are new technologies of social action that help them promote their causes. When the Pew Research Center surveys people, it generally finds that, despite the problems, people think that being networked is positive for their lives.

As individuals’ trust is shifting away from major institutions, their trust is invested more in personal networks. Our personal networks are segmented and layered, and composed largely of weak ties. It may be that, beyond strong and weak ties, we need a layer of ‘audience ties’ – people we don’t necessarily know, but who follow us on social media. There is more personal liberation in networks, but more work involved in rallying people to help you when needed. There is more importance now attached to factors like trust, influence, and awareness: our friends have become the information sentries and gatekeepers in our lives. People also turn to their networks to evaluate information, and meaning-making may start there with the help of friends.

We live in an unusual time in that we have seen three revolutions unfold over recent decades: the arrival of the internet/broadband; the arrival of mobile connectivity; and the arrival of social networking/media (which allow the reification and refinement of social networks). The trend now is to use two or more social networking platforms, making strategic calculations about which platforms to use for which purposes. The fourth revolution is now on our doorstep in the form of the internet of things, and it will have profound implications for our lives. In Western countries, Pew may soon stop asking people whether they use the internet, because it will be so embedded in everyday life.

For networked individuals, information becomes a ‘third skin’ (after our original skin and our clothes); it changes our experience of our selves and others, and how we think and remember. Secondly, ‘birth realities’ are complemented by ‘my tribes’. Thirdly, people participate in the ‘fifth estate’ (referring to social media, going beyond the fourth estate of journalism).

Lee Rainie concluded with three examples of the kinds of social and political activism which are enabled in contemporary networked culture – a dying American boy who was able to obtain experimental drugs from a pharmaceutical company, which led to his recovery; environmental and anti-corruption campaigns in China, which have turned local issues into national issues; and US communities’ responses to Hurricane Sandy, which involved sharing local information on social media platforms. All of these demonstrate that the implications of networking are considerable. They also demonstrate that altruism runs deep in human beings and that new technologies can facilitate it in powerful ways.

All in all, the WUN Global Digital Cultures Conference succeeded in bringing together many ideas and themes from across disciplinary areas. I’ve no doubt that everyone left with their insights into their own areas of study and research enriched with insights from overlapping and parallel areas of study and research.