International Mobile Learning Festival

Bangkok, Thailand

27-28 May, 2016

Sukhumvit Skyline, Bangkok, Thailand. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2016. May be reused under CC BY 3.0 licence.

It was great to have a chance to attend the International Mobile Learning Festival for the second year in a row. It was transplanted this year from its original Hong Kong base to Bangkok, where it drew together global perspectives on the conceptualisation of mobile learning, interwoven with regional perspectives on the implementation of mobile learning. It was particularly interesting to note the importance of open resources and platforms in developing world contexts which are beginning to explore the possibilities of mobile learning. Fortunately, the proceedings are available online.

In his opening keynote, Empathic technologies and virtual, contextual and mobile learning, Pedro Isaías explained that researchers have concluded that emotional responses play a pivotal role in learning processes. It may be that an intelligent computer which can learn needs to have emotional responses. He gave an overview of recent generations of social robots, from Nexi to the Dragonbots at MIT. He went on to talk about the differences between affective technologies, which are typically robots responding to human emotions within the context of human-machine interaction, and empathic information systems, like online learning platforms which use emotional data in applications to provide a more personalised learner experience. He spoke about the EU Empathic Products research project, now concluded, which set up numerous trial scenarios involving empathic technologies.

Forums are empathic by nature, Pedro suggested, but we can increase the empathic elements. In particular, he demonstrated the Umniverse massive collaboration platform, an empathic online learning environment. Users have to add empathic data to posts and can tag existing posts with such data, in order to make them easier to sort and find later. Users also have access to system statistics allowing data mining on forum activities. Such approaches can help address the absence of face-to-face communication in distance learning, and can transpose interaction into an online context. They can have a positive effect on interest and motivation. He went on to outline the current, ongoing evolution from Umniverse to the 3D immersive environment TAT, and invited interested educators to contact him about possible collaboration in investigating this new platform.

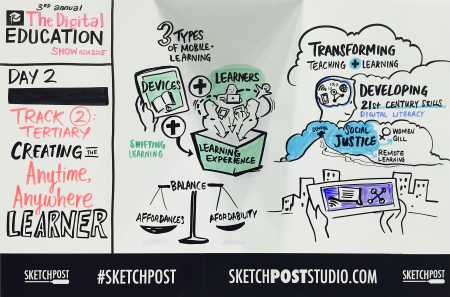

In her keynote which opened the second day, Moving towards a mobile learning landscape: Effective device integration, Helen Crompton suggested that we should be asking what we can do with mobile technologies that we couldn’t do with tethered learning. She cited John Traxler’s list of five key aspects of this learning, which can be:

- contingent

- situated

- authentic

- personalised

- context-aware

However, research shows that educators are not currently integrating mobile devices effectively into the curriculum. Educational leaders have many fears around mobile devices. Many educators stick to methods that they are familiar with, thereby using 21st century technologies with 20th century teaching methods. She commented that the TPACK and SAMR frameworks can provide useful supports for educators in incorporating new technologies effectively into their teaching.

Leveraging the insights of TPACK and SAMR, she then went on to describe an m-learning integration framework covering 4 elements as seen from the point of view of the teacher:

- Beliefs (about the role of the teacher; socio-cultural influences; self-efficacy; past experience as a learner)

- Resources (including training; technical support; access to technology)

- Methods (online or face-to-face teaching; teaching philosophy)

- Purpose (time-filler or meeting objectives; substituting or redefining learning)

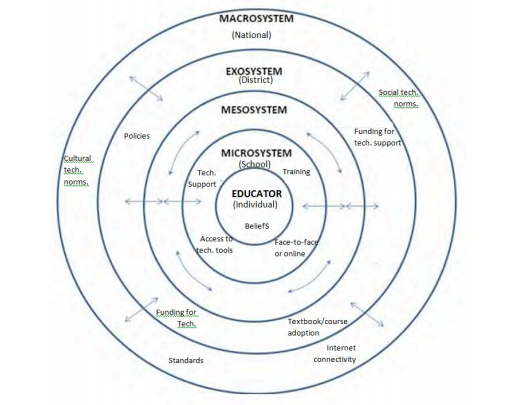

She further suggested that there is a nested social and ecological framework for mobile learning integration, with concentric circles leading from the educator (individual) through the microsystem (school), mesosystem and exosystem (school district) to the macrosystem (national scale).

In my own presentation, Mobile literacy: What it is, why it matters, and how it can be developed, I argued that in order for our students to get the most out of their mobile learning experiences, we need to help them develop their mobile literacy, building on existing literacies like information literacy, multimodal literacy, network literacy and code literacy. I then wrapped up with some comments on critical mobile literacy.

In their talk, Mobilizing the troops: A review of the contested terrain of app-enabled learning, Michael Stevenson and John Hedberg outlined the progression through web 1.0 and web 2.0 and towards cloud computing. Apps, they suggested, have emerged as the key mode of learning with mobile devices. They outlined three key metaphors reflecting the issues that educators have had to face in recent years:

- Sending the Troops “Over the Top” Before They’re Ready?

- Equipping the Troops with an AAA: Atomized Arsenal of Apps

- “Smashing” the Arsenal for More Pedagogical Firepower

When teachers and students are literate enough in the use of apps, they can choose to combine a variety of apps to expand learning possibilities; this approach is known as “app smashing“, as demonstrated in the YouTube App Smash Tutorial by mrshahnscience:

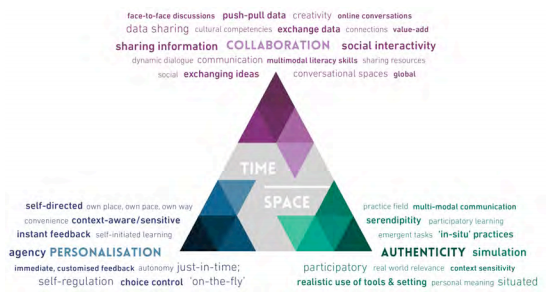

In their presentation, A snapshot of teacher educators’ mobile learning practices, Kevin Burden and Matthew Kearney spoke about the mobile pedagogical practices of teacher educators. They referred to their Mobile Pedagogy Framework, as seen below, where word clouds offer some detail about the three constructs of personalisation, collaboration and authenticity:

‘Word clouds’ relating to the 3 constructs of the Mobile Pedagogy Framework. Source: Burden & Kearney (2016)

They reported on a study which showed that teacher educators have a high focus on authenticity but less of a focus on networking and personalisation in their current use of mobile pedagogies. Teachers reported that the above framework is a useful tool in conceptualising mobile pedagogies, and a toolkit is now being developed to support the professional development needs of teacher educators. This involves a tool to help teachers and students evaluate task design with reference to the above framework, as well as multimedia case scenarios to illustrate best practices. There will also be a dynamic poster showing how certain apps might support the three constructs of personalisation, collaboration and authenticity. A course is being set up, and the presenters invited interested educators to contact them to become involved in shaping or participating in the course.

In his workshop, Do mobile devices have a central role in e-learning?, Spencer Benson focused on the changing landscape, with the move from teacher-centred to learner-centred education, and a parallel move from laptops to mobile devices. To a large extent, he suggested, students don’t discriminate between academic and non-academic uses of mobile devices; all uses are integrated on the same devices. Using Poll Everywhere, he surveyed the audience on numerous topics connected with the use of mobile devices in education.

In his talk, e-Seminar apps: Technology-enhanced learning interventions through “real-time” online interactive experiences, Kumaran Rajaram discussed the creation of the prototype iSeminar e-learning app developed at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. He explained that the app is designed to promote student interactivity and engagement, which is particularly important in a cultural context where students may be reticent to interact verbally. The app also facilitates group work and peer evaluation. A learning analytics component is valuable in giving the instructor an overview of students’ thoughts and understandings. Records of the discussion contents can also be kept for future review. In sum, the question that is really being asked here, he suggested, is how the technology can be of optimal use, so that online interaction can become an organic part of a routine class.

In his presentation, Mobile learning design and computational thinking, Thomas Chiu spoke about Jeannette Wing‘s (2006) claim that computational thinking will be a fundamental skill used worldwide; he suggested that, to obtain good employment in the Hong Kong context, it will soon be as necessary as an ability to speak English. Computational thinking has three main components: problem formulation; solution expression; and solution execution and evaluation. In K-12 education, he went on to say, computational thinking is not just about technical details for using software, or thinking like a computer, or even necessarily programming. It does not always have to involve a computer. He presented three case studies which showed that problem formulation is fundamentally about collaboration and communication; solution expression is about visualising, modelling and presenting ideas; and solution execution is about implementation, sharing ideas for revisiting, and real-time experiencing of ideas. Mobile devices, he suggested, could have a role to play in supporting all of these.

In his presentation, Using wearable technology to improve the acquisition of new literacies: A new pedagogical approach of situated individual feedback coming from the activity trackers and reflected upon in the ePortfolio, Michele Notari discussed the intersection of new wearable devices with new digital literacies. He then went on to focus on eHealth literacy, which he defined as the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and to apply the knowledge to address or solve a health issue; it simultaneously draws on other literacies ranging from information to scientific literacy. He reported on a study involving undergraduate students at the University of Hong Kong who wore Xiaomi MiBand fitness trackers over a period of 5 months. Students’ reflections revealed the considerable changes some of them made to their exercise and sleeping behaviour during this time, while a number did further online research to improve their understanding of the statistics being generated, especially in regard to sleep.

A broad regional perspective was offered by Jonghwi Park in her presentation, UNESCO and mobile learning, where she explained that the UNESCO Bangkok office serves a whole range of countries in the Asia Pacific region. She spoke about the successes of the UNESCO Education for All (EfA) goals in the Asia Pacific region, particularly in regard to more children attending school, but she mentioned some unanticipated side effects: these include a shortage of teachers; a global learning crisis centred on the quality of learning; and growing demand for higher education. Following the end of EfA in 2015, new United Nations Sustainable Development goals were set up for the 2015-2030 period. The fourth of these refers to universal quality education. ICTs, she suggested, will be crucial in making this a reality. She mentioned that there will shortly be a new UNESCO report released which examines member countries’ national education policy orientations, and compares the extent to which government policy emphasises opportunity vs risk mitigation and safety. She spoke about UNESCO initiatives to promote teacher training, and to foster gender equality in learning through mobile technologies; in connection with the latter point, she highlighted the 2015 UNESCO report Mobile phones and literacy: Empowerment in women’s hands.

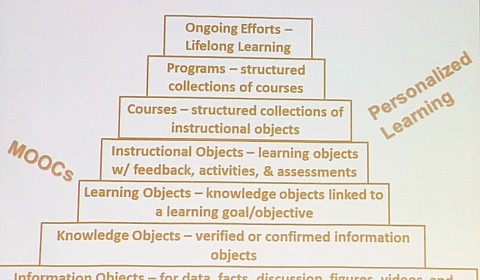

A number of presenters spoke about individual country contexts. In his presentation, Thailand OER, OCW and MOOC: Strategy toward lifelong learning of Thai people, Anuchai Theeraroungchaisri highlighted the open element in all of these platforms: OERs, OCW, and MOOCs. He spoke about the role of the Thailand Cyber University (TCU) in creating an e-learning consortium of all Thai universities, providing online distance education, and engaging in research and development in e-learning including establishing quality assurance guidelines. There are now 9 universities in Thailand serving as e-learning hubs. The TCU open courseware project has led to the TCU-Globe initiative, designed to facilitate the sharing of open resources within and outside Thailand. The latest development is the Thai-MOOC project, which will be launched in 2016 and will tie into the goals of the larger Digital Thailand project, which involves creating a digitally driven knowledge economy.

In her presentation, The growing tendency of mobile-assisted language learning development in Kazakhstan, Damira Jantassova spoke about a whole range of MALL practices employed in Kazakhstan. Reporting on an interview-based research project with 500 EFL learners at Karaganda State Technical University, she noted that the vast majority of interviewees placed most emphasis on learner mobility (focusing on the anytime/anywhere aspects of learning), a smaller number placed emphasis on device mobility, and a very small number placed emphasis on mobility of learning experiences. Mobile phones were primarily used for vocabulary development, according to students. She suggested that it is important to help students develop an understanding of the potential contextual benefits of mobile learning.

In his talk, Mobile solution for synchronized and offline version of audio-based open educational resources, Reinald Adrian Pugoy spoke about the recent dramatic increase in mobile phone ownership in the Philippines, with many students now preferring to use mobile devices rather than desktop or laptop computers to access educational materials. This is against a background of limited infrastructure and slow internet connections, with many educational institutions located in remote areas with little or no internet access. Offline OERs do not provide a viable solution because materials may quickly become out of date. He reported on a study at the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOP) exploring a mechanism to allow offline use of OERs, with an internet connection only needed to download the most recent updates. It was decided to explore audio OERs, to be stored in a WordPress repository. Offline accessing and syncing of OERs has been successfully achieved in this project, with the next stage being to conduct a usability evaluation among end users.

All in all, this was a conference which offered rich insights both into local contexts as well as into their connection with global themes and trends. It will be interesting to revisit some of these themes when IMLF takes place back in Hong Kong in mid-2017.