The Digital Education Show Asia

Kuala Lumpur

15-16 June, 2015

The third annual Digital Education Show Asia once again brought together educators from around Asia to discuss key themes in contemporary educational technology, from mobile learning to MOOCs, and big data to the internet of things.

In his opening plenary, What does learning mean?, Sugata Mitra suggested that the idea of knowing is itself changing, a point he illustrated with examples going back to his Hole in the Wall experiment in 1999 in India, which was repeated with World Bank funding across a number of other countries from 1999-2004. In every case, groups of unsupervised children working on computers in safe, public spaces were able to teach themselves how to use computers, download games, and learn some English. He found that generally they could acquire a level of computing literacy equivalent to that of an office secretary in the West in 9 months. Within 4-5 months after that, students had learned how to use a search engine to discover the right answers to questions set in their school homework. His conclusion was that groups of children using the internet can learn anything by themselves.

He found, moreover, that the process could be facilitated by an adult, not necessarily a knowledgeable one but a friendly one, who encourages the children. This is the grandparent approach, which differs from the prescriptive methods typically adopted by teachers and parents. The Skype-enabled ‘granny cloud’, formed in 2009, doesn’t only consist of grandparents, but of a wide range of adults interested in the education of children. They are beamed into remote locations where there is a lack of good teachers. They don’t teach – they ask questions. This is effectively a self-organised learning environment, or SOLE, where the ‘granny’ amplifies the process.

A SOLE can easily be set up in a traditional classroom. The essential elements are broadband + collaboration + encouragement and admiration. The furniture gets removed and around 5 computers with large screens can be introduced, with students working in self-selecting groups to try to answer questions which are posed to them. This method began in Gateshead in 2010 and spread from there across England and into Europe, and by about 2012 it had gone viral across the world.

However, teachers complained that this approach doesn’t work well in the last few years of schooling, when they need to prepare students for final examinations where there is no internet available. Mitra suggested that the examination system was born to train office workers of the early 20th century in reading, writing and arithmetic; workers had to read instructions and follow them without asking questions. He asked: Why is the school system continuously producing people for a purpose that no longer exists? Nowadays, he said, employers are looking for creativity, collaboration and problem-solving, which are skills that reflect the office environment of the 21st century. Why should an examination be the only day in students’ lives when they don’t have access to the internet? Allowing the internet into the examination hall, he suggested, will change the entire system. He went on to discuss the kinds of questions being asked in exams, and suggested that many of them have little relevance to students’ future lives, and can in any case be answered easily with Google. The old system was a just-in-case learning system; but we don’t need much of this knowledge for our everyday lives or careers.

He used the analogy of cars doing away with the need for coachmen, because the passengers became the drivers. He asked whether it is possible, in the same way, for learners to become the drivers of their own learning. This, he said, is the idea behind the school in the cloud, or SinC. A number of these environments have now been set up to explore whether it is possible to implement SOLEs remotely around the world. Results so far suggest that: reading comprehension increases rapidly, students’ self-confidence and self-expression improve, aspirations change, internet skills improve rapidly, teachers change their approaches, and SinC works better inside school than outside school. SOLEs, he went on to say, also work for skills education, undergraduate education, and teacher training and professional training.

In his paper, Will learning analytics transform higher education?, Abelardo Pardo suggested that learning analytics can involve a wide variety of stakeholders: students, instructors, institutional managment, parents or policy makers. The term ‘learning analytics’ is usually used to talk about course or departmental analytics, while ‘academic analytics’ refers to institutional, regional, or national and international analytics: but these are different levels of the same process. One challenge is how to combine very different data sources for different stakeholders. Another challenge is finding the right algorithm to cover, for example, statistical prediction, clustering and profiling (identifying features of groups within a larger population), relationship mining, link prediction in networks, and text analysis. Finally, once we have conducted the analysis, we have to decide what to do about it: how will we act on the data? So we need to link stakeholders to data sources, forms of analysis, and actions to be taken.

Co-operation between different actors and sections within institutions is essential, meaning that leadership is necessary to set up a data-intensive culture which becomes a culture of change. The term ‘data wranglers’ is being used by some researchers to describe those who liaise between members of these multi-disciplinary groups. He finished by outlining 3 scenarios: a weekly student engagement report giving personalized feedback, strategic advice for the rest of the semester, and even advice for the year; a summary for instructors indicating what students have done over the week; and finally, feedback for the institution on degrees, infrastructure, and the student experience.

In his paper, Big data for the win, Eric Tsui suggested that institutions should not only focus on internally collected data, but should consider external, historical data. He extensively discussed the cloud, with its 3 kinds of connections: machine to machine, people to machine, and people to people. He asked whether we can draw more intelligence from the cloud. He gave illustrative examples of how systems like ReCAPTCHA and Duolingo crowdsource data. He also offered a detailed example of a cloud-based PLE&N platform using Google tools, which is scalable and robust. There are challenges in big data, he suggested, around privacy, what data to collect, and the fact that historical data haunts every instructor and learner.

In the paper, MOOCs – Where are we at now?, Dr. Daryono gave a list of reasons for implementing MOOCs, ranging from extending reach and access, through building and maintaining a brand, to innovation. He outlined the differences between cMOOCs (derived from the connectivist movement, linked to the development of OER) and xMOOCs (which are highly structured, content-driven, and largely automated). There are many types and versions of MOOCs curently emerging. In the future, more recognition is needed for MOOCs, and we should work towards collaborative, affordable, consumer-driven MOOCs.

In her paper, To MOOC or not to MOOC – Considerations and going forward, Dina Vyortkina noted that people who take MOOCs are generally not fresh to education, tend to be in their thirties or older, and need English to engage in the majority of MOOCs. Drivers for institutions setting up MOOCs include a desire to increase equitable access, to disseminate courses, to advance resarch, and to innovate technologically and pedagogically. From a global perspective, developing countries are underrepresented when it comes to the offering of MOOCs; government initiatives may help. Some see MOOCs provided by Western countries as examples of pedagogical or even cultural imperialism, with few local connections.

It has been suggested that MOOCs fit well with blended or flipped learning approaches. One German study suggests that bMOOCs – blended MOOCs – offer the best of both worlds, i.e., face-to-face and online teaching. However, it’s important that educators check the provider conditions, since some prohibit use of MOOC materials for tuition-based courses. It’s also important for educators to consider how the materials fit with their own teaching philosophies, and whether the content is entirely appropriate.

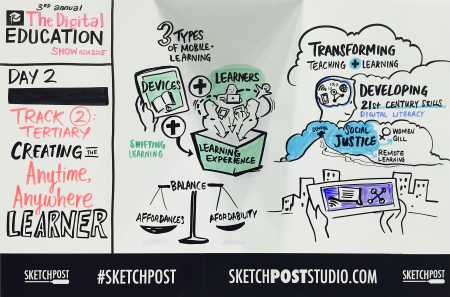

In my own paper, Creating the anytime, anywhere learner, I spoke about how capitalising on the full potential of anytime, anywhere learning generally involves exploiting a high level of affordances of mobile devices for learning, which correlates with a low level of affordability of those devices in the current context. Using a series of examples, I showed that anytime, anywhere learning may not be necessary in every context, but that where it is possible, there is considerable potential for transforming teaching and learning, and developing learners’ 21st century skills. (See the summary of my presentation recorded by the conference artist below.)

In his paper, Mobile learning for language learning: Trends, issues and way forward, Glenn Stockwell talked about the challenges of mobile learning outside the classroom. He noted that learning in real-world contexts can bring external disruptions, but also disruptions from inside the learning device itself. He discussed pull and push learning; with pull learning, students need to take the initiative themselves, but in push learning, material is sent automatically to students and they are more likely to pay attention to it. All in all, however, teachers are more enthusiastic about mobile learning than students are, and some learner training (not to mention teacher training) is necessary. Based on research conducted with Phil Hubbard, he suggested that students need technical training (how to use mobile devices for learning), strategic training (what to do with them), and pedagogical training (why to use them). He reported on a study which showed that pedagogical training can dramatically increase students’ participation in mobile learning.

In her paper, How can mobile learning best be used for online distance learning?, Tae-Rim Lee outlined some lessons from the Korean National Open University, which has now progressed through three generations of mobile learning services, as devices and connectivity have evolved. It was found to be important not to depend on any one network or operating system. M-learning content has been shortened to be more atomic in nature; it was found that students preferred approximately 20-minute videos. Segmentation allows students greater control over the content through which they are working. Many changes have been implemented in response to student feedback.

Together with Glenn Stockwell, I moderated a roundtable in the final session of the conference, with the title of Driving success in mobile learning – Challenges and considerations. It was an opportunity to chat to participants in more detail about implementing mobile learning in their own particular contexts and, specific differences notwithstanding, to see that there are many similar challenges and considerations in this area across the globe.

All in all, this was a very enjoyable event, which offered a chance to hear the perspectives of educators from around Asia, and a chance to network with educators facing similar questions and issues around the world.