XXIIIrd International CALL Conference

Brisbane, Australia

3-5 October, 2025

As expected, the International CALL Conference had a strong focus on integrating generative AI effectively into education, entailing the need for both educators and students to develop their AI literacy. Given the conference theme of Inclusive CALL, many papers also discussed the ambivalent role played by genAI in respect of diversity, equity and inclusion – and how best to use it to serve the purpose of inclusion.

In his keynote presentation on the first day, Ethical and emotional responses to AI integration in language education: Insights from a qualitative case study and a Q methodology investigation, Lawence Jun Zhang referred to Son’s (2023) comment that AI in language education is not a singular tool but a broad spectrum of technologies, and suggested that teachers need to take on different roles with respect to AI. He reported on a PRISMA review of teachers’ use of AI. Under AI literacy, researchers identified the following themes: understanding AI; AI application in pedagogical practices; prompting and interaction with LLMs; AI ethics and concerns; challenges and barriers; and professional development and training needs. He reported on a second study looking at teachers’ emotional reactions to AI. The themes to emerge were: positive emotions facilitating adaptation; AI-induced negative emotions like anxiety, stress and cognitive overload; emotional regulation and coping strategies, including adaptive and avoidance coping; ambivalence and mixed emotional responses, highlighting the coexistence of optimism and apprehension; and institutional and pedagogical implications, emphasising the influence of institutional structures.

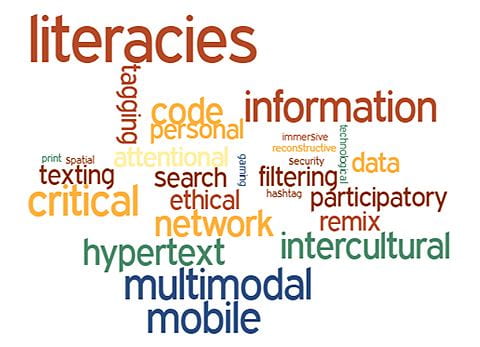

In my own keynote, Where do humans fit in? CALL, AI and human agency, which opened the second day, I argued that the balance between human agency and AI agency is one of the most important issues in contemporary education, and is closely linked to questions of diversity, equity and inclusion. I began by taking a step back to observe the big picture of our contemporary era, viewing it through three intersecting frames – the postdigital, the posthuman and the sociomaterial – and asking how these might help to inform our understandings of human and AI agency. I went on to consider humanity’s two major encounters to date with AI, their impact on the so-called personalisation of both our networks and our learning, and the implications of such personalisation in terms of personal agency. I argued that personalisation may not in fact be a suitable term or concept to describe or capture these developments, with individualisation or customisation being preferable alternatives in many cases. My main focus was on three possible strategies that we as language educators can promote with, and for, our students: developing AI literacy to build and bolster human agency; promoting co-intelligence to balance human agency and AI agency; and practising design justice to develop human agency for the marginalised. Adopting such strategies allows us to capitalise on the benefits of AI while tempering its drawbacks, as we work to build human agency and promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

In their pre-conference workshop, Beyond access: Designing inclusive learning with AI and VR/AR tools for language learners, Wen Yun and Yuju Lan covered both AI and XR tools and their role in inclusive language learning. Yuju Lan explained that a pedagogical AI agent should be a proxy of a human teacher, who remains responsible for the overall design. She described teacher education classes where teachers develop pedagogical agents for their own contexts, including the possibility of agents embodied as robots. She also showed examples of AI agents embedded in VR environments. Ultimately, it is important that students can transfer the skills they are practising with AI and in VR environments to real-world settings. Wen Yun described a vocabulary learning tool called ARCHe for Singaporean Primary 2 students. In the newer ARCHe 2.0, students write a text to describe a picture, with the AI then generating a pictorial version of their text as a comparison. Students can further modify their description until the AI-generated image better matches their writing. AI literacy is a byproduct of this approach. She went on to describe a goal-driven conversational agent designed to improve the writing of Primary 4 students; this focuses on shared agency between the AI and the students, with the AI supporting students’ goal-oriented activities. There is a study currently underway to determine the efficacy of this approach.

In her paper, Bridging the AI divide: Exploring AI literacy among migrant and refugee adult learners in Australia, Katrina Tour stressed the growing importance of AI for everyday learning and life, hence the need to develop language students’ AI literacy. She went on to introduce the Sociocultural Model of AI Literacy by Tour, Pegrum & McDonald (2025). Reporting on a national survey of learners in a language education programme, she noted that the majority, as of late 2023–early 2024, had not even heard of, let alone used, generative AI: this is a group which is very much in need of learning about AI and developing AI literacy. Among those who used genAI, some used it for learning (e.g., supporting homework using multiple languages in a translanguaging paradigm), everyday tasks (e.g., finding recipes), leisure pursuits (e.g., scripting vlog episodes), and professional activities (e.g., creating marketing materials). However, capabilities were fragmented, with a lack of understanding of how genAI works and the need to apply a critical lens to genAI output. She concluded that there is a growing AI divide; while some learners are experimenting with basic operational and contextual AI, advanced critical and creative skills needed targeted support. AI literacy interventions and AI literacy programmes are thus needed for language learners.

In their paper, Enhancing EFL students’ human-centred AI literacy and English motivation via ChatGPT co-writing, Hsin-Yi Huang, Chiung-Jung Tseng and Ming-Fen Lo described an advanced writing course where students took a translanguaging approach to strategically using ChatGPT for writing support. They mentioned the importance of students developing critical and creative skills to apply to all generative AI use. Teachers have an important role, they suggested, in guiding students to embrace human-centred values and creativity.

In their paper, Beyond standard English: AI-driven language learning for inclusivity in South Korea, So-Yeun Ahn, Han Jieun, Park Junyeong and Kim Suin demonstrated an AI chatbot capable of conversing in multiple World Englishes and responding to students’ comments and questions in a conversational format. They reported on a study with 200 Korean learners, where one group could access multiple World Englishes and the other was exposed only to Inner Circle Englishes. Initially students indicated more satisfaction with Inner Circle Englishes, but the World Englishes group tended to produce more complex utterances to elaborate about their personal experiences. It was found that Inner Circle accents reinforced traditional curricular topics, while World Englishes accents elicited more diverse, identity-linked or cultural topics. World Englishes changed how students talked; AI wasn’t only a language partner but also a cultural persona, with students positioning the AI as representative of a national identity. This does however raise ethical and pedagogical questions about how AI voices should represent national identities.

In their presentation, Feedback in the generative AI era: A critical review of generative AI for L2 written feedback, Peter Crosthwaite and Sun Shuyi (Amelia) described a PRISMA-informed scoping review of 51 empirical studies of genAI feedback on L2 writing. The most common aim of such research was to identify an impact from ChatGPT on improving writing; in second place was reporting student/teacher perceptions of genAI feedback; third was comparing genAI to teacher-generated feedback. Most of the studies looked at post-writing feedback, rather than feedback at the planning or early stages of writing; this is an area for future investigation. Many studies showed significant gains, with teacher and AI feedback being complementary, and a combination of teacher and AI feedback being more effective than either alone. One methodological problem identified was that assessments of writing quality were not necessarily related to the type of genAI feedback; another was small sample sizes; yet another was that many studies did not provide information on the genAI prompts used. Overall, it would seem that there are gains from genAI L2 writing feedback, but the field is still developing.

In their paper, TPACK co-construction of pre- and in-service EFL teachers toward the integration of corpus and AI, Oktavianti Ikmi Nur and Qing Ma described the Indonesian school teaching context where internet access is quite varied, and where pre-service teachers are often tech-savvy but lack pedagogical expertise, while in-service teachers are strong in pedagogy but lack digital skills. They described a study looking at how pre-service and in-service teachers co-construct TPACK with respect to corpus linguistics and AI. It was suggested that AI tools are now becoming normalised in teaching, while there is less familiarity with corpus tools. Collaboration between pre-service and in-service teachers is an important mechanism for bridging technology gaps in teacher repertoires.

In their presentation, A large-scale mixed-methods study of Japanese university students’ use of ChatGPT for L2 learning, Louise Ohashi and Suwako Uehara reported on a July 2024 survey of 2,521 Japanese university students looking at whether and how they were using ChatGPT. It was found that 50.1% were using it for language learning, with a focus on writing, grammar and vocabulary. They reported on the top six themes to emerge: feedback on own work; translation; vocabulary; grammar; conversation practice; paraphrase or summarise. Around 2% of responses indicated academic integrity issues ranging from obvious cheating to suspected misuse. They concluded that students were typically using ChatGPT for basic support, with deeper exploration limited; generative AI literacy is needed.

In their paper, Fostering inclusivity through the incorporation of e-readers in online Mandarin classrooms, Liu Chuan and Jing Huang suggested that e-readers can be powerful tools for inclusion, autonomy and plurilingualism; can promote student agency and choice; and can support equitable, responsible and identity-affirming teaching practices. They reported on critical dialogue between teachers which led to reflective, transformative practice.

In his paper, The effects of a personalised learning plan in a language MOOC on learners’ oral presentation skills, Naptat Jitpaisarnwattana quoted Downes’ (2016) distinction between personalised learning, which involves tailoring learning to individual needs, and personal learning, which emphasises learner autonomy and self-directed engagement. Considerations include technology infrastructure, learner traits, learner culture, and the nature of the subject matter. He reported on a study of personalisation in MOOCs which found that many students did not follow personalised pathways to the end, with those who deviated from the prescribed pathways showing a greater preference for more autonomous approaches to their learning. He then went on to describe a more recent study looking at 178 science major students in an Academic English course in Thailand, where a personalised learning plan was generated for each student, with course analytics used to track whether students followed their plan. Significant improvements were found across a range of language areas and skills. He concluded that personalisation is often associated with adaptive learning, where students are offered adaptive recommendations (a strong form of personalisation), while here the personalised learning plan provided students with a possible pathway tailored to their profiles and self-identified needs, leaving students some room for autonomy (a weak form of personalisation). This weaker form of personalisation may a valuable feature in an era increasingly dominated by algorithm-driven edtech.

It’s clear that, while we are still in the early days of generative AI adoption in education, important understandings are already beginning to emerge concerning the need for both educators and students to develop AI literacy, and the need to take a nuanced and judicious approach to using genAI if it is to support diversity, equity and inclusion.