MTech Conference

Guilin, China

27-29 June, 2017

Shanhu Lake, Guilin (杉湖, 桂林), China. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2017. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

The inaugural MTech Conference, based on the MTech Project and its underpinning MTech Survey, drew together teacher educators from Asia and Europe to discuss how best to integrate mobile technologies in teacher education internationally. It is hoped that this will be the first in an ongoing series of collaborative events involving the MTech Network.

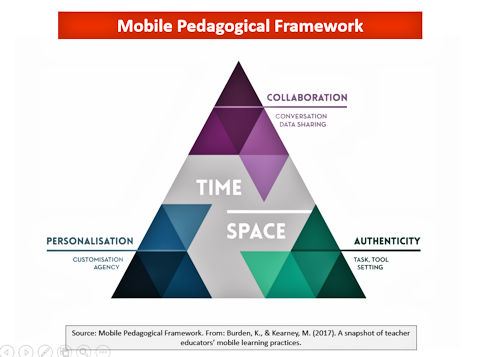

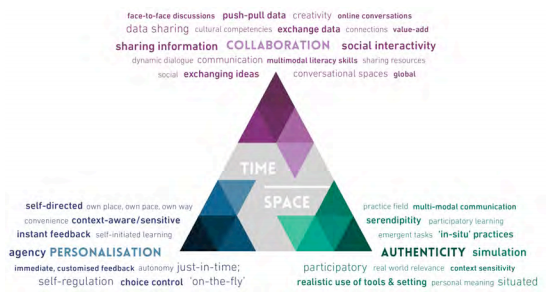

In our opening presentation, Mobile learning in teacher education: Beginning to build a global overview, Kevin Burden and I gave an overview of the MTech Project and the underpinning survey of technology use by teacher educators around the world. We outlined initial insights emerging from the first round of data collection, based on 96 responses, with a little under two thirds from Asia, and a little over a fifth from Europe. We showed for example that relative to the iPAC Mobile Pedagogical Framework (see image below), teacher educators typically report more evidence of personalisation and collaboration than authenticity in mobile learning activities.

Interesting insights are also beginning to emerge around themes of seamlessness and intercultural learning. We invited attendees and their colleagues to complete the survey, which has now entered the second round of data collection, with the aim of increasing the overall number of responses and especially obtaining responses from regions of the world which are currently underrepresented in the data.

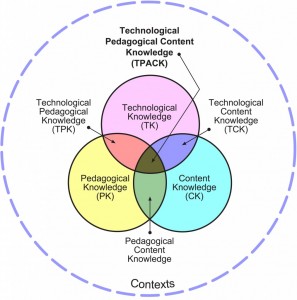

In a presentation reflecting the Chinese context at GXNU, Developing pre-service teachers’ ICT in education competencies and curriculum leadership, Xibei Xiong referred to the TPACK Framework in describing a proposed ICTs in education curriculum which should include TK, TPK, TCK, and TPCK. Curriculum leadership, she said, shapes teacher education programmes by providing supportive policies, managing the curriculum, and evaluating pre-service teachers’ learning outcomes. Teacher education programmes may in turn shape the practices of curriculum leaders in terms of changing the education system requirements. Curriculum leaders at university level have a role to play in policy formulation and resource allocation; at school level, they have a role in determining educational curriculum structure, course objectives and academic credit management; and at classroom level, they have a role in developing course content and pedagogy.

In a presentation from the Singaporean context, Understanding teachers’ design talk for the co-creation of seamless science inquiry, Ching Sing Chai discussed the TPACK Framework and its various revisions and extensions in recent studies, before coming to focus on TPASK (Technological Pedagogical And Science Knowledge). He suggested that teachers need to design instruction with technology in order to develop their TPK; they should learn through designing in a collaborative community; they should be supported with appropriate scaffolds; and finally they need to engage in reflective experiential learning. Design talk embedded in a dialogic design, he went on to say, is key to supporting the emergence of TPACK. Sustainability and scalability ultimately come through teachers, so teacher development is more and more important in today’s world.

He described a Singaporean study involving the 5E (Engagement, Exploration, Explanation, Elaboration and Evaluation) approach for science inquiry-based learning, used as a PCK framing. Teachers talked about designing lessons for Grade 3/4 students. Mobile devices were used in various ways, including for seamless science learning (for example, students taking pictures and explaining heat sources in their own houses). The software used included KWL, Sketchbook, MapIt, Blurb (from the University of Michigan) and other tools (Nearpod, PowerPoint, Google, etc). The content of teachers’ design discussions was analysed to identify references to TK, PK, CK, TPK, TCK, PCK, TPCK, and CTX (representing context). A lot of the initial discussion was about TK but this element declined over time; conversely, the amount of discussion involving PCK increased over time, as did the discussion involving TPASK (but this was at a much lower level). CTX featured strongly but also decreased over time. The resulting model is quite different from the theoretical TPACK model (see image below).

In a presentation from the Hong Kong context, Cultivating academic integrity and ethics of university students with augmented reality mobile learning trails, Theresa Kwong and Grace Ng showcased the mobile AR TIEs (Trails of Integrity and Ethics) developed by HKBU and its partner institutions in a Hong Kong-government funded project (a project on which I am also a consultant). As Theresa pointed out, this is learning in the style of Pokémon Go, but in fact this project began around 18 months before the release of Pokémon Go. It is all about linking the environment to relevant educational content, in this case related to themes of academic integrity and ethics. Given that students find these AR trails motivating and helpful in connecting theoretical content with their everyday lives, this is an approach which is highly relevant to present and future educators and teacher educators.

In a presentation from the Taiwanese context, Mobile learning x cloudclassroom = ?, Chun-Yen Chang suggested that the spread of mobile devices along with BYOD policies means that the moment is right to be implementing mobile learning. The Taiwanese Ministry of Education has run collaborative projects on mobile learning in schools, and has set up a Teaching Application Mall of educational apps. He went on to describe his CCR (CloudClassRoom) project which supports mobile-assisted anonymous quizzes and presents teachers with aggregated data. It can be used, he said, in museums, outdoors, online, and in the ‘Asian silent classroom’. Polling students before and after lessons can be an ideal way of tracking changes in their understandings.

In a presentation from the Australian context, Teaching teachers how to go mobile: What’s happening in Australia?, Grace Oakley suggested that although mobile technologies are being used in many Australian schools, mobile learning is not developing as quickly as might be hoped, nor are its boundaries being pushed. There are many policy barriers, she added, including duty of care issues, funding, behaviour management issues, cybersafety, testing regimes, school processes, and equity issues. She then illustrated some activities with mobile devices being carried out in primary schools: oral retelling with Puppet Pals; learning prepositions with a camera and the Book Creator app; media presentations with Tellagami; and mobile augmented reality learning trails created with FreshAiR. She wrapped up with a discussion of how digital technologies, digital literacies, and mobile learning are beginning to feature in initial teacher education courses as well as in resource platforms for practising teachers, such as the Digital Technologies Hub. She indicated that some pre-service teachers are beginning to create mobile learning activities for their students, but she concluded by asking whether they are getting enough opportunities to do so.

In a presentation from the Irish context, Mobile learning on an initial teacher education progamme – MGO programme, Seán Ó Grádaigh showcased the technological changes that have occurred in the last decade. Uber is the largest transport company in the world, but has no cars; Facebook, Twitter and WeChat are the largest content platforms in the world, but they produce no content; Alibaba is the largest shopping mall in the world, but it has no shops; and Netflix is the largest cinema in the world, but has no movie theatres. However, he argued, we haven’t seen a game-changing application in education yet. Still, given the speed of changes, we need to be educating students for the future.

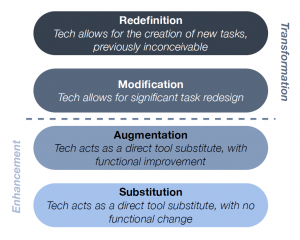

There is a misconception that better technology – from kitchen mixers through cameras to gym equipment – will lead to changes by itself. The same is true in education. But what is required is a vision, a plan, professional development, and pedagogical (as opposed to technological) training. In terms of the technology available, most schools are way ahead of most teacher training programmes, a situation that needs to change.

He went on to suggest that using technology to facilitate reflective practice by pre-service teachers may be a game changer. His students are asked to do reflections – hot reflections straight after a class, and cold reflections where they later revisit their initial reflections – using text, audio, video, or videoconferencing. He showed an example of a teaching video with a voiceover where the pre-service teacher provided commentary on her performance. She then received feedback from two tutors. The five steps followed in this task are:

- Students create and construct a lesson

- Students deliver and record it

- Students watch and analyse it

- Students create a reflective voiceover on their video

- Students receive feedback on their reflection from tutors

He continued by suggesting that digital technologies can help to recreate immersive learning contexts for language learning as well as other subjects. However, rather than passively listening or watching, it is better to build inquiry activities around multimedia materials like videos. Teachers and students can also become actively involved in multimedia creation. Involving students in ‘teach-back’ activities is a great way to check that they have understood what they are learning.

In another presentation anchored in the Hong Kong context but with wide global relevance, entitled Learning design and mobile technologies in STEM education, Daniel Churchill explained that STEM is an approach to learning that removes traditional barriers separating science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and integrates them into real-world, rigorous and relevant learning experiences for students. It aims to improve learning in STEM areas; improve teaching effectiveness; deal with the shortage of STEM professionals in the future; include minorities, achieve gender balance, and provide opportunities for low-income members of society; decrease unemployment; foster international competitiveness in the 21st century; and help provide solutions to internationally pressing problems. Ideally, STEM should be not only multidisciplinary (where concepts and skills are taught separately in each discipline but housed within a common theme) or interdisciplinary (where there is the introduction of closely linked concepts and skills from two or more disciplines with the aim of deepening understanding and skills) but transdisciplinary (where knowledge or skills from two or more disciplines are applied to real-world problems and projects with the aim of shaping the total learning experience). There are both scientific and engineering approaches to STEM; in the latter, there are phases of problem scoping, idea generation, design and construction, design evaluation, and redesign. Challenges include insufficient teacher training; insufficient teacher knowledge of STEM; insufficient funding; insufficient laboratory resources and technicians; insufficient community support and media coverage; preferences for music, sport, and academic subjects; a student focus on exam preparation; learning computer coding without any logical or systematic thinking; and a focus on rote memorisation and a lack of depth of conceptual understanding.

He went on to explore six key affordances of mobile technologies for STEM:

- multimodal content (e.g., in the form of dynamic, interactive learning objects)

- linkage of technologies (i.e., a mobile phone can connect to a whole ecology of digital devices)

- capture (e.g., taking photos or making videos, capturing GPS position and acceleration, etc)

- representation (e.g., programming a robot, making a digital story, creating a presentation, etc)

- analytical (i.e., processing and looking for patterns in data)

- socially interactive

Combining these affordances, he suggested, leads to new learning possibilities. Key tools include robotics, 3D printing, and cognitive tools.

He concluded by saying that STEM should not be just another science, maths or technology class. Learning design based on (pre-) engineering tasks is the critical strategy for STEM education, he argued, and STEM can be conceptualised based on an interaction model. Mobile and emerging technologies are essential for enabling STEM: these include virtual reality, augmented reality, wearables, and so on.

In his presentation, Key issues in mobile learning: A research framework, Pedro Isaías spoke of a range of current developments and challenges in mobile learning. He began by talking about the ubiquitousness pillar of mobile learning. He described the development of mobile LMSs, but mentioned that they have generally not really been designed for mobile devices. He asked whether they can be truly mobile-friendly without compromising navigation. He went on to emphasise the importance of creating responsive designs by following these guidelines: use mobile-friendly layouts, compress content, concentrate on the essential, format your text, and test the course on several platforms.

He went on to address the authenticity pillar of mobile learning, stressing the role of wearable technologies in education: for example, for interactive simulations, facial recognition for identifying students, creating first-person videos, and enhancing game participation. The challenges include cost, design concerns, privacy issues, familiarisation with the interface – digital literacies are needed here – and technical challenges. Augmented reality, he said, also has an important role to play in promoting authentic learning: it increases student engagement, mediates between students and the world, supports problem solving, enhances motivation, and provides access to real-world scenarios. One challenge is that students may become overly focused on the technology rather than the learning, and there are cost implications. He illustrated his comments with a video about the SNHU (Southern New Hampshire University) AR app, and a video about simulated 3D objects generated from textbook images with Arloopa. Gamification, too, can contribute to authenticity. Gamification should not be about external rewards, but about learning objectives. It enhances student motivation, provides ubiquitous access to resources, facilitates authentic and situated learning, improves peer interaction, promotes technical literacy, and fosters teamwork. Mobile learning game essentials, he said, are: an introduction and logo, instructions, a game objective, questions, feedback and results.

He then addressed the personalisation pillar of mobile learning, which is linked to mobile learning analytics, artificial intelligence, and geolocation. There are some concerns around data privacy and informed consent with analytics. With mobile intelligent systems, advantages include the fact that students can be taught according to their knowledge; adaptive learning methods; individualised adaptive teaching; explanation of teaching content; and automatic generation of exercises. Some LMSs provide geolocation features: this allows delivery of content according to location, designing of location-based online content, reaching a global audience, and consideration of cultural differences. Geolocation examples include language-adaptable subtitles, scavenger hunts, and geocaching games.

Finally, he addressed the collaboration pillar, which is about social learning and the e-society. Mobile learning harnesses the potential of social learning, promoting collaboration, discussion and knowledge exchange. But it is important to consider the quality of the interactions, and to think about the role of the teacher in the students’ discussions. Mobile learning involves the production of multimedia content, allows ubiquitous access to information, encourages the development of digital literacy, and creates informed citizens. There may be some issues around data privacy and security, and we must ask whether an increasingly mobile society may lead to an expansion of the digital divide.

In a presentation looking at future developments in mobile learning through wearables, The research on pedagogical feedback tactics of affective tutoring system based on physiological responses, Qin Huang suggested that in time wearable devices will be able to detect humans’ real emotions by registering physiological signals. She gave details of a study making use of the OCC emotional classification model, which is one of the most complete models and the first structural model used in the field of artificial intelligence. With good calculability, she said, it is widely used in the field of emotional computing.

Sun Tower (日塔) & Moon Tower (月塔), Guilin, China. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2017. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

The conference concluded with an MTech Steering Group meeting to discuss future directions for the MTech Network, how to gather more responses to the MTech survey and collaboratively publish our research, and when and where to meet again for another conference event. It is likely that the second MTech Conference will be held in China in late 2018.