MobiLearnAsia Conference

Singapore

24-26 October, 2012

[See also Day 2 blog post]

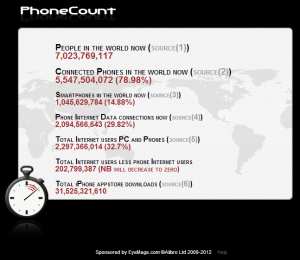

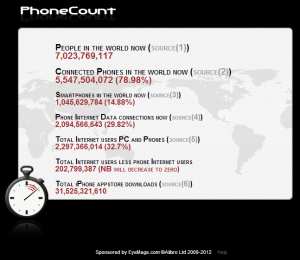

The inaugural MobiLearnAsia Conference in Singapore has brought a much-needed regional focus to the emerging field of mobile learning. As the global phone count goes up (see image below), m-learning will become an ever more important strand of education. This conference drew together some of the world’s foremost experts in the area and showcased many local and regional initiatives. In fact, because of the richness of the content, I’ve divided this blog post into Day 1 and Day 2. The third day was devoted to full-day workshops.

Screenshot of Phone Count tally, 25 October 2012 (http://phonecount.com)

In his opening keynote, Mobile Learning: Past, Present & Future, Gary Woodill noted that there are different histories that underpin mobile learning. Learning before classrooms was mobile and social, and people learned by watching and talking to others. The printing press allowed standardisation, which helped foster the rise of modern classrooms. In the 1770s in Prussia many modern schooling concepts were developed: the idea of sitting at desks; putting up your hand for questions; recess and detention. Students were immobilised behind desks.

Mobile learning restores the idea of being in context while you’re learning. There is a long tradition of learning without classrooms, on field trips, excursions, in apprenticeship situations. Mobile learning taps into this tradition.

One of the first school level mobile projects was the Wireless Coyote Project, run by Apple in 1991. In 1998, the HANDLeR project was run at the University of Birmingham by Mike Sharples. Clark Quinn defined mobile learning in an article in LiNE Zine in 2000, and then a flurry of mobile learning articles followed. Initially people saw mobile learning as an extension of e-learning, but now the focus has changed to the learner being mobile. The first mLearn conference was held at the University of Birmingham in 2002. IAMLearn was launched in 2007.

Mobile learning, Woodill argued, is an ecosystem consisting of devices, networks, and so on. We are just at the start of Stage 2 in the scheme below:

- Stage 1 – New technology applied to old problems (including coursebook & textbook delivery online, and use of LMSs, which are an example of a classroom metaphor that has not left us yet)

- Stage 2 – Variations and mashups – struggle for ‘dominant design’

- Stage 3 – New uses, new improved technologies

Key affordances of mobile technologies include:

- Mobility

- Ubiquity

- Accessibility

- Connectivity

- Context sensitivity

- Individuality

- plus more

New uses of mobile technologies, which come under Stage 3, include:

- Social networking (e.g., ordinary users of the net spreading news before journalists report it; or users of InstantMe, the mobile version of PatientsLikeMe; there is a real sense of community and emotional connectedness)

- Data Collection (e.g., citizen science such as on a mobile app like HealthMap)

- Live Trend Tracking (e.g., improved responses to disasters and outbreaks, or data on traffic jams, often provided automatically by phones without user input)

- Just-in-Time Information (e.g., the Baby helpline on 511411 in the USA; QR codes and Google Goggles also fit in here)

- Augmented Reality (e.g., see the Medical training Augmented Reality video)

- Mobile Games (e.g., the How Healthy is Your Food? app)

- Location-Based Apps (e.g., the WikiMe app)

- Storytelling (can create records and put them together in specific ways)

- Lifecasting (allows you to learn by revisiting experiences at a later date)

- Performance Support (e.g., on-the-job support, medical support for post-operative patients – this is a trend towards DIY health)

- External Interactivity (e.g., the BBC Bird Flu billboard in New York, where the public could text in responses)

- Haptics (e.g., the hug shirt or the kiss phone)

- Self-Tracking (e.g., tracking your own exercise, heart rate, etc; see The Virtual Self by Nora Young; there is also a trend towards self-tracking of informal learning: for example using Tin Can API, an extension of SCORM, or an app like Tappestry)

- Co-ordination (e.g., for emergency services; ‘vote mobs’)

- Collaboration

- Collective Behaviour (as seen in the Arab Spring)

Woodill’s predictions for the near future (around 5 years) include the following:

- Mobile becomes ubiquitous (‘MobiComp’) (as we move from mobile learning to context-aware u-learning, using sensor technologies, mobile devices, and wireless communications)

- New mobile interfaces arrive (such as contact lenses which measure health from fluid in the eyes)

- Mobile devices become embodied (see: Mobile Interface Theory by Jason Farman, e.g., on the use of brainwaves to control technology)

- Mobile learning goes 3D

- A new gesture control language (including ‘surface computing’, where there are projections onto your hand or body)

- Sensors become integrated (see: Body Sensor Networks edited by Guang-Zhong Yang)

- Device shape shifting (see: The Shape-Shifting Future of the Mobile Phone by Fabian Hemmert on TED)

In summary, before classrooms, learning was social, contextual and mobile, but classroom learning immobilised learning. Web 2.0 led to networked social learning. Mobile devices have now led to mobile learning. Woodill suggested that using mobile devices only in the classroom is like only using your car radio while parked in the garage.

We’re already beginning to move beyond mobile learning. Education and training have become mobile, networked, cloud based, curated, open, social, informal, location-based, shared, contextual, ubiquitous, peer generated, learner generated, filtered, collaborative, gamified, and personalised. What will we call this? It’s not just mobile. We don’t have a good metaphor for this yet.

He concluded by outlining the ongoing impact of mobile learning along the following lines:

- Continuous learning for all

- Everyone can be a learner, everyone can be a teacher

- Increased access for those lacking education

- Innovation can come from anywhere

- New generation of leadership in technology

- Organisational disruption

In their talk, Oceans of Innovation, Sir Michael Barber and Saad Rizvi gave important background and context to others’ presentations on mobile learning, as they discussed the content of their recent publication of the same name.

A thousand years ago, the centre of gravity of the global economy (measured by GDP) was in Asia, but there was a gradual shift of dominance towards Europe and America. From 1950 onwards, we saw Asian economies begin to rise again, and in the last 10 years we have seen the most dramatic shift in history towards Asia. This will continue in coming years.

There are major challenges ahead in the coming half century, which require global leadership. But there is no clear leadership at the moment. Global leadership develops when there is innovation, which leads to economic growth, which leads to economic influence, which in turn leads to global leadership. As the centre of gravity shifts eastwards, the important leaders of coming years may well be from the Pacific region. More precisely, the future leaders will emerge from the education systems of this region. The PISA results and TIMSS results show that there are very effective education systems in the Pacific region. An average 15-year-old in Singapore is performing about 2 years ahead of an average 15-year-old in the UK or US. They even have a lead in English, though it is a second language for many.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that these students have other skills like entrepreneurial skills. In other words, is the education system as measured by PISA and TIMSS enough to generate the kind of innovation and leadership that is needed to address global issues? No – it’s a good foundation, but it’s not sufficient. Well-educated means: E ( K + T + L), i.e.,

- E [Ethical Knowledge]

- K [Knowledge, i.e., Know-What & Know-How]

- T [Thinking = all teachers helping students to think in different ways, creatively or deductively, rapidly or reflectively]

- L [Leadership = the ability to influence those around you, to be persuasive, to be empathetic and listen, to influence decisions on all levels).

Countries like Singapore are well-placed to develop this knowledge and these skills, and develop global leadership.

They suggested that we need to rethink 45-minute back-to-back lessons. Maybe students can use mobile technologies and learn outside the classroom. The flipped classroom model provides one option. We also have to find ways of using new technologies to assess and test the new skills in new ways. Students can acquire reading, writing, maths skills at the same time as they learn new skills.

Barber and Rizvi presented an Innovation Framework for future education, arguing for whole system reform as well as systemic innovation leading to whole system revolution. With the educational changes of recent years, Singapore, Hong Kong, Ontario, Finland (they suggested that though it is a very unique society and its lessons are difficult to replicate, what we can learn from is Finland’s recruitment of the most talented people into education) and Australia (under Julia Gillard’s reforms) are among the countries and regions which are best placed to get this set of changes right. Technology and mobile learning will be an important part of this. They noted that an excessive deference – as is sometimes found in some Asia-Pacific nations – can limit innovation. Students have to learn to question, to challenge, to debate. Much of the world’s innovation comes from large, diverse cities, and Singapore is well-placed in this regard.

In his presentation, Technology Enabling Education, Suan Yeo, from Google Enterprise Education, gave an overview of current trends from Google’s perspective. He noted that the second billion smartphone users are now coming online around the world (see: The Second Billion Smartphone Users by Jon Evans). How we learned is not how our students learn.

It was the case 20 years ago that students went to school to access sophisticated equipment; but now the equipment students have at home is often more sophisticated than what is at school. The kids growing up today are going to expect technology to just work; they don’t want to think about messy operating systems, upgrades, patches and so on. Some things students of the future won’t need to learn include how to use paper maps; how to use a mouse; or how to burn CDs or DVDs. Banning new technologies in class is not an answer; students find a way around bans. Instead, we need to teach students how to use technologies, about digital citizenship, and so on. Learning analytics is a current major trend.

He made a number of points related to the growing importance of mobile learning and, in particular, Google’s emphasis on the browser as the key platform of the future:

- Mobile has become students’ first choice for internet access.

- Technology has to enable learning outside the classroom. Many schools are shifting away from closed classrooms and moving to an open learning model.

- Using the OLPC program, the next generation of users can leapfrog a generation.

- Using open technology is crucial in education – through the Khan Academy, Udacity, Gooru, Coursera and so on.

- It is important to give everyone open access to information. Whatever the platform or operating system, the one common factor is the browser.

- Google is starting to view the web as a learning platform. Google is betting that the web is here to stay, and so delivers many services through the web. It believes that the browser (notably its own browser, Chrome) will become the desktop of the future. This allows a unified experience as you move between different devices, e.g., desktop computer, tablet, mobile phone.

- Google’s tools like Gmail, Google Docs, and so on, are designed to allow you to access anything from anywhere.

- Google Docs allows people to collaborate from anywhere.

- YouTube is Google’s second most popular service after Google Search. YouTube is now the second largest search engine in the world. There are more than 700,000 educational videos on YouTube. YouTube is also a way of connecting with other people and crowdsourcing your learning.

- Google’s Project Glass might allow people to get rid of phones eventually with wearable technology (see Project Glass on Google+ or the Project Glass: One Day … video on YouTube)

In his talk, Scaling Up Mobile Learning, Chee-Kit Looi asked what kind of curriculum we need to make use of the affordances of mobile technologies. While it may work in one classroom with one teacher, how can we make it work for the average teacher? Many countries are going 1:1, but what is a good pedagogical model that is sustainable? And how do we bridge informal and formal learning?

There are both planned and emergent learning spaces mediated by 1:1 mobile devices; some are outside class and some are in class:

- Type I: Planned learning in class

- Type II: Planned learning out of class (e.g., an excursion)

- Type III: Emergent learning out of class (e.g., students use mobile phones to capture pictures)

- Type IV: Emergent learning in class (when students inquire about some element of the lesson)

A smartphone can be a learning hub for all these types of learning, and it can be an essential part of the lessons. In comparing primary science classes, one of which worked with mobile devices integrated into their learning, there was improvement in student scores. Having students create animated sketches can help the teacher identify misunderstandings, for example. The teacher felt it deepened the students’ thinking and improved the quality of the questions they were asking.

There are advantages of scaling up this approach:

- The research study showed gains in subject matter, positive attitudes to subject learning, new media literacy, and good learning habits – self-directed learning

- There is more holistic learning with mobile devices as learning hubs to support seamless learning inside and outside the classroom

- Teachers developed constructivist practices

Strategies for scaling up include:

- Regular sharing at the TTTs

- Teachers practise mock lessons

- Lesson study through video-recorded classroom sessions

- Customising lesson plans for high, middle and low achievers

Success with mobile devices is due to these factors:

- Curriculum integration; the devices are not just an add-on

- Mobile devices are personal to students and they have 24/7 access

- Intensive PD

- Strong leadership support

In summary, a mobilised curriculum can make a difference to students’ learning (engagement, self-directed learning, and collaborative learning). It is important to find ways of scaling it within schools and across schools.

In her presentation, Mummies, War Zones, and Pompeii: The Use of Tablet Computers in Situated and On-the-Go Learning, Terese Bird outlined three projects involving mobile technologies:

- Mummies: Windows tablets were used by Museum Studies Masters students (not 1:1). This involved a cleverly designed PowerPoint presentation which had the feel of an app, and included information and videos from British Museum staff. It was used to support students on museum trips. At the same time, students could make their own multimedia recordings. They had to email in their multimedia-rich reflections by 10am the next day, which led to a much richer learning experience.

- War Zones: iPads were used by MSc in Security, Conflict and International Development students on a 1:1 basis. The iPads contained a tailored app, SCID, designed by KuKuApps of Leicester, including key learning resources like e-books and OERs which could be accessed even without an internet connection. Many of the students were located in conflict zones and could not always access the internet.

- Pompeii : archaeology researchers in Pompeii used iPads to superimpose archaeological data on photos. This supported note-taking, and data was synchronised wirelessly with a central database.

Thus, on Day 1 of the conference, a wide range of devices and platforms was presented, with presentations cohering around the value of mobile learning both in enhancing the classroom and in fostering contextual learning outside the classroom.