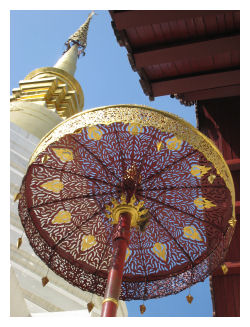

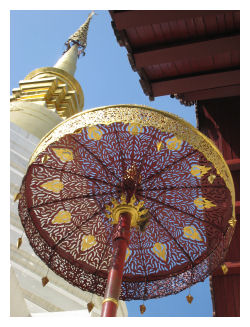

GloCALL 2009

Chiang Mai, Thailand

8-11 December, 2009

As always, the GloCALL Conference provided a good illustration of its own key theme – that the global + the local = the glocal – in the mix of presenters and attendees in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai. A major theme running through many plenaries and papers concerned the ongoing shifts in technology and its use in education.

As always, the GloCALL Conference provided a good illustration of its own key theme – that the global + the local = the glocal – in the mix of presenters and attendees in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai. A major theme running through many plenaries and papers concerned the ongoing shifts in technology and its use in education.

In the opening plenary, Integrating ICT into teaching and learning English in Thailand, Thanomporn Laohajaratsang noted that because teachers tend to teach the way they were taught, they sometimes struggle with the integration of new technology into the classroom. For the new generation of students, the so-called net generation or “screen-agers” (defined here as those born in the 2000s), this will increasingly be an issue. The slogan of the screen-agers, according to Thanomporn, is: “I, me first, I-Pod, Myself, My own needs”, and their preference is for learning from the network of people surrounding them rather than from teachers.

But classrooms are changing: she presented a range of examples of technologically enabled teaching, ranging from the sophisticated use of feedback mechanisms in lectures to the use of OLPC laptops in developing areas. Citing Rik Schwier’s (2008) model of “Learning Theories Supported by Computer-based Learning”, she noted a move over time from software that supported objectivist and cognitivist educational approaches towards software that supports constructivism and connectivism, with a parallel move from individual learning to group learning. She argued that we should not overlook the power of social software like blogs, wikis and social networking sites.

In her plenary, Why the social in sociocollaborative CALL, Carla Meskill pointed out that in CALL we’ve moved from a ‘because we can’ paradigm (where pedagogical considerations were not paramount) through an ‘intrinsic rewards’ paradigm to a ‘communication with others’ paradigm. There has been considerable support from psychology and, more recently, neuroscience for the notion that human beings are socially responsive by nature and that all learning is social. Recent research suggests that humans respond to computer screens similarly to the way they respond to each other. Our responsiveness to screens has moved from text through noise, movement, simulated people and on to web 2.0, or social networking.

Teacher responsiveness has only recently been recognised as a critical component in successful student learning, especially the learning of discourse norms. Responsiveness is about instructional conversations orchestrated by a teacher – and nothing can replace a really excellent human teacher, Carla argued. We need to refocus CALL on what excellent teachers do – on the instructional conversations by which they teach, and on creating instructional conversations that render our machines and screens optimally responsive. It is the person on the other end who is responsive, not the machine.

Sociocultural CALL acknowledges language growth and learning via the recreational web 2.0. There is a lot of language, responsiveness and literacy – social literacy – on which language teachers can capitalise here. We have to get our heads around this kind of social literacy. A sociocultural view of CALL sees teacher-orchestrated instructional conversations with students, on screens, as essential. It’s not sufficient to just send students off to practise by themselves; rather, teachers need to respond to teachable moments, to who learners are, to their needs. The pedagogical implications are extensive. The machine is now at the service of human instructional interactions – and that means, at the service of really excellent language educators. Sociocollaborative CALL, Carla concluded, is about humanware and teacherware to which learners are optimally responsive. Teachers ultimately need to embrace this technology because it can amplify and extend their already excellent practices.

Carla opened her paper, The language of teaching well with digital learning objects, with a quote by Andrea diSessa: “Information is a shockingly limited form of knowledge” (Changing Minds, 2000). She then went on to discuss digital learning objects, which she described as designed to be under student control and open to exploration. They are dynamic and multimodal, so the term is not used to refer to static worksheets, pages of text or overheads. These learning objects can be seen as:

- public

- anarchic

- malleable

- unstable

- providing anchored referents

Appropriate instructional conversation involves thinking and speaking that is:

- joined in a dialectic way

- dynamic, generative, process-oriented

- cumulative with the goal of shared, mutually generated understanding

Teacher strategies might include saturating; linguistic traps; modelling; form-focused feedback; and providing linguistic/thinking tools.

Carla offered a number of oral synchronous examples. When a student is searching for a particular vocabulary item, the teacher can draw visual cues from a databank or quickly Google an image (which will become an increasingly important skill for teachers). This can be done not only in a face-to-face classroom, but in a virtual classroom in Second Life. Oral asynchronous examples can include models of physical gestures, or threaded asynchronous voice conversations where, with the help of images, the teacher provides cues and responses.

In his plenary, Tom Robb asked: Can we still call CALL CALL? Referring to Stephen Bax’s notion of normalisation, he pointed out that computers are now becoming everyday tools. Using Wordle diagrams, he showed that terms such as ‘CALL’ and ‘computer’ are no longer mentioned very often in conference paper titles or abstracts; the emphasis has shifted from the tools themselves (which are slowly disappearing as a focus) to the processes (collaboration, etc). He suggested that it might be better to change the term ‘CALL’, since people are less conscious of the role of computers as normalisation sets in; anyone can do CALL but they don’t necessarily see it as their primary interest; and often we’re not actually using computers any more but mobile technologies.

The new game in town, Tom suggested, is access outside the classroom. This is important, given the high number of hours required to progress at higher levels of language learning – especially as we tend to give students fewer contact hours as they advance. In other words, we need to increase the number of language contact hours without increasing class time. CALL outside the classroom wasn’t possible as an integral class component until recently – but universal access is now a reality in many areas and expanding rapidly elsewhere, and tracking is possible. Tracking makes the difference between making CALL material available and using the material effectively. Technology can be an ‘enforcer’, by tracking students’ use of material. If material can’t be tracked, teachers should use alternative means of keeping students accountable, like printed copies or screenshots.

There are different kinds of self-access: true self-access by motivated, independent learners; recommended self-access, where a teacher recommends that a student needs practice in a particular area; required access, where access counts for grades; and class access, where everyone is working in a lab. Only the last two are really viable with dependent learners. Tom argued that we shouldn’t try to eliminate more restricted CALL drill exercises, where the teacher steps out of the picture, suggesting these can be valuable for some students in some contexts. That means the teacher can save class time for non-CALL work in areas where teacher presence is important.

He finished with the following summary list of conclusions:

- Use of technology is shifting from a focus on the tools to a focus on procedures

- Use is shifting from in-class use to out-of-class use

- Out-of-class use requires suitable tools to monitor and encourage use

- Result: more contact with the language and improved language skills

- Need for academic societies to help teachers use effectively those aspects of technology that they are starting to take for granted.

The 3-paper symposium Meeting places for the local and the global? Telecollaboration and intercultural learning on web 2.0 focused on the advantages and disadvantages of telecollaboration, and the need for new literacies and new understandings of intercultural interaction.

Sarah Guth and Fran Helm began by discussing the need for changing definitions of culture (with the rise of online cultures) and literacy (with the rise of digital literacy) – and the need for a concept of second generation telecollaboration, involving three domains (Byram’s five savoirs, they argued, need to be complemented by the CEFR foreign language skills and new online literacies) and three dimensions (operational, cultural and critical). They then went on to offer a practical example, the Soliya Connect Program, a telecollaboration project involving students in the West and in the Arab and Muslim world.

In my paper, entitled Web 2.0 ::: Space 3.0, I argued that in a rapidly globalising world, it is vital for educators to help students develop intercultural competence and, more specifically, epistemological humility (Ess, 2007) – essentially, the recognition that their own perspective on the world is not the only one. Drawing on the work of Bhabha, Kramsch and others, I briefly described the notion of an intercultural third space, before going on to describe an educational third space, defined as a third space purposely fostered in an educational context for educational purposes, and governed by social constructivist principles of deconstruction and reconstruction of knowledge and understanding. In the best cases, the mediated interaction which takes place in such a space can lead to intercultural learning and a growth in epistemological humility. I finished up by examining a series of web 2.0 and web 2.0-related tools (discussion boards, blogs, wikis and virtual worlds), showing how they can be used as platforms for the emergence of an educational third space, and outlining some examples of successful practice from language learning programmes around the world.

Marie-Noëlle Lamy rounded off the symposium in a paper which asked: Is ‘interculturalism’ an obstacle to telecollaboration 2.0? She pointed out that there are in fact numerous tensions and failures in telecollaboration projects, many of which are not necessarily linked to either ‘language’ or ‘culture’ per se. Reporting on a recent collection of essays co-edited with Robin Goodfellow, she indicated that three main themes had emerged:

- individuals and their self-image (which is not necessarily connected to nationality or culture in any simple way – individual psychology often comes across more strongly than ethnicity)

- the ‘imagined community’ (people are influenced by the rules of the imagined community to which they belong, as well as the understanding they construct of the online community)

- the tool: neither neutral or passive (tools carry cultural assumptions and may not be culturally appropriate in all contexts)

The overarching theme, then, was not so much how ‘to communicate’ online but how ‘to be’ online. Conclusions to be drawn for teaching include:

- the need to move from culture-as-essence to culture-as-construction

- the need to redefine ‘local’ conditions as > 1st click to last click (i.e., local = local to the online situation)

- the need to look out for the many, unexpected cultural strata that impact on the intercultural life of a student group.

Technologies continue to be widely explored, exploited and developed. In his paper, Not alone: Developing a model for a new Consortium for Language Teaching and Learning, Andrew Ross described the US-based Consortium for Language Teaching and Learning, consisting of Ivy League schools and other US institutions, which existed from 1987-2009 to support language learning. A task force constituted in 2008-2009 reviewed the purpose of the Consortium, which now consists of seven members. The plan is to share curricula, courses and instruction and pool resources between institutions, especially to promote the learning of less widely taught languages. This may involve distance and/or blended learning, which is different from the traditional face-to-face model typical at these institutions. Institutions will thus be able to contribute in different areas (providing instruction, resources and/or students) in different languages.

In his paper, Developing an intelligent reading system for vocabulary learning, Glenn Stockwell observed that language teachers cannot always be aware of which vocabulary their students don’t know. He described the development of an intelligent system to create individualised vocabulary exercises for students depending on which hyperlinked words they clicked on in online reading exercises.

In Digital mentoring for student teachers, Peter Gobel focused on using technology as a mentoring tool, where mentoring is defined as a relationship where there is transmission of knowledge and experience alongside relevant psychosocial support. Describing teacher training programmes in Japan, Gobel noted that trainee teachers on school placements often find there is a clash of educational philosophies with their host teachers, and they have little peer support available. One possible solution involves peers and near peers providing feedback during placements, by using an online space to create a digital community for discussion, problem solving and general support and encouragement.

Advantages for students include: such a space is accessible (including from mobile phones), builds up an archive of material over time, and allows communication and engagement with peers. Advantages for the programme include: the space can be used for debriefing, teacher trainers can use it for monitoring and trouble-shooting, and because an archive is built up it can be used to better tailor the programme for future students. A useful strategy involves students recording thoughts in a daily diary, reviewing their diaries, and reflecting on their teaching in groups and as individuals. Results of a pilot project have been positive, with trainee teachers exchanging and analysing ideas as a group.

In the paper Improving English language and computer literacy skills, co-authored with Jeong-Bae Son, Henriette van Rensburg spoke about developing language and computer literacy skills for refugees, with particular reference to Sudanese refugees in Australia. At the start the refugees in the pilot group had no idea what kinds of activities they could do with computers and needed instruction in basic functions, but they were extremely keen to learn and made good progress both in computing skills and associated key language. Internet images were extremely helpful for deciphering vocabulary. The participants were particularly interested in images of Sudan, around which they were able to share stories and memories. Rensburg concluded that the net provided authentic materials that enhanced language learning and computer skills, and noted that the researchers were impressed by how participants improved their computer literacy in a short space of time.

In the closing colloquium, participants commented positively on the mix of presenters and presentations at the conference, but also reflected on the need to find additional ways to reach out to greater numbers of local teachers in conference locations. Next year’s GloCALL venue has been announced as Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia.

In the closing colloquium, participants commented positively on the mix of presenters and presentations at the conference, but also reflected on the need to find additional ways to reach out to greater numbers of local teachers in conference locations. Next year’s GloCALL venue has been announced as Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia.