The Inn at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Photo by Mark Pegrum, 2019. May be reused under CC BY 4.0 licence.

The IAFOR Conference on Educational Research & Innovation

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, USA

6-8 May 2019

It was an honour to be asked to present a keynote paper at the inaugural IAFOR Conference on Educational Research & Innovation, held in Virginia, USA. Focused on the theme of ‘Learning Beyond Boundaries’, and with attendees from across state and national borders, the conference delivered a strong message about the importance of working across disciplinary and other boundaries.

In her opening keynote, Context is everything: Rethinking evidence beyond boundaries, Amy Price Azano offered a critique of evidence-based practice as an urbanised and often decontextualised approach, suggesting that practice-based evidence is a socially just alternative in diverse contexts. Despite longstanding evidence of inequalities among students, the search continues for sameness in determining what works; however, this ignores the salience of context. Practice-based evidence is about attending to context: it involves identifying local needs; selecting, planning and implementing; and examining and reflecting. It recognises that students are not the same, nor are contexts. She suggested that, going beyond place-based pedagogy, place can provide a philosophical foundation, content and context, method, and evidence.

She noted that rurality should not be seen as a factor to be overcome, but as a viable and valuable context for nuanced understandings about what works across diverse contexts, and outlined a research project currently being carried out on rural gifted education. One key question is how a bright child in a socioeconomically deprived area can be given the message that he or she is bright and gifted, without also getting the message that he or she needs to leave the area.

In my own keynote, Mobility, mixed reality, and the crossing of linguacultural boundaries, I looked at a series of innovative m-learning projects where mobile devices serve as lenses allowing students to cross the boundaries between educational and non-educational spaces, as well as between the real and the digital, and between languages and cultures. As such, mobile devices can benefit a diverse range of learners with a diverse range of learning needs.

In his keynote, Research beyond boundaries: Educational psychophysiology, Rich Ingram spoke about a new field of research, educational psychophysiology, which concerns the measurement of learning-relevant psychological states and performance for the purpose of informing teaching and learning design. The focus is on examining continuous data in real-world settings.

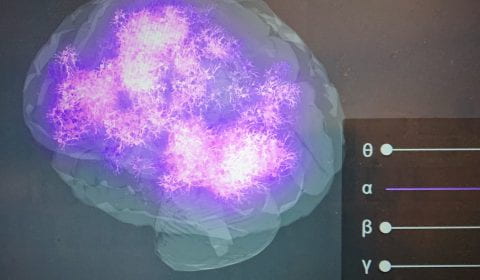

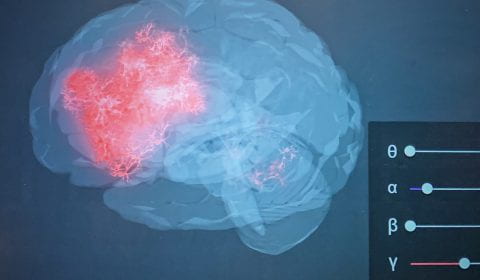

The following day, Rich Ingram ran an informal workshop where it was possible to try out the equipment used for physiological measurements, including an electroencephalogram (EEG) monitor (measuring electrical activity in the brain), an eye tracking bar (also incorporating pupillometry), a heart rate monitor (measuring heart rate variability), and a Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) sensor (measuring skin conductance). It was fascinating to observe the kinds of data obtained and how it can be read (see the photos below of me using brain imaging software, and the associated images of my brain activity). It was also revealing to see how portable and relatively affordable the equipment has become. The current issues in the field are that there is far more data being collected than can easily be analysed, and that it is still unclear how to interpret much of the data. To some extent, it is a matter of asking the right questions and finding meaningful correlations – but already new insights are beginning to emerge, for example regarding attention and distraction with the use of digital technologies. This is an exciting space to watch over coming years, with plenty of scope for more researchers to get involved.

Mark Pegrum using EEG brain imaging technology. Photo by Rich Ingram, used by permission.

In his keynote, Anatomy of flipped classrooms, Robert Doyle suggested that a flipped approach is based on student involvement theory, and also allows students to develop important skills beyond knowledge acquisition, including higher-order thinking, communication skills and metacognitive skills. He spoke about Bergmann and Sams who initially developed flipped learning to reach students who missed class on snow days, and used voiceovers and annotations in PowerPoint slideshows to present their material online. He mentioned four different categories of presentation: audio recording, voiceover, screencasting, and video. Videos can be produced in one-button or full-service studios, with certain trade-offs between the two approaches; the latter allow higher production quality and they involve the support of skilled technicians, but incur higher costs.

Some of the advantages, he said, include students viewing materials at their own pace; students encountering concepts at least twice, before class and in class; and class time being used for more effective learning activities, with faculty and students interacting directly during class. Disadvantages include potentially less engaging lectures where students can’t ask questions; a significant time commitment; technical problems; and varying quality and student access. Key design principles include providing an opportunity for students to learn before class; checking to ensure students arrive in class prepared; and making a clear link between pre- and in-class activities. He suggested that for every hour of face-to-face lecturing, it takes at least four hours to record, edit and upload a comparable digital lecture, and noted that when flipping a class, it is worth beginning with a single module or section of a course. Automated captioning is a useful inclusion.

In his paper, Online teaching in a mobile era: Pedagogy, policies, and the cultural transformation, Martín Sueldo referred to the work of Antoni Gutiérrez-Rubí, indicating that we find ourselves in a new mobile reality where cellphones have become extensions of ourselves. He spoke about the need for education to take on board these changes, and discussed the importance of institutional online learning policies as well as training, support and mentoring for faculty. He suggested that there is a need for a ‘liquid pedagogy’ (based on Zygmunt Bauman’s liquid modernity) which can take different forms in different teaching contexts.

In the talk, Professional development in an international context: Fostering intersections between technology and culture, Kevin Oliver, Ruie Pritchard, Angela Wiseman and Michael Cook spoke about a US teacher development programme preparing teachers to use emerging technologies to introduce cultural lessons to, and enhance the cultural understandings of, their own students; weekend campus classes were followed by a short study abroad period. Teachers were asked to build Weebly portfolios, sharing project work and evidence of increasing cultural understandings in three areas: cultural connections, cultural collections, and cultural reflections. Regarding culture, teachers increased their personal understandings of other cultures, and came to better recognise and address diverse cultures represented in their own classrooms. Regarding technology, teachers enjoyed the opportunity to be placed in the role of students. The researchers concluded that culture-focused PD can impact how culture is addressed in the classroom, and that technological tools and writing can impact teaching and learning about culture. Past programme websites and teacher portfolios can be seen at:

- Integrating Writing and Technology in England

- Finnish Connections, Collections, and Reflections

- Swedish Connections, Collections, and Reflections

- Czech Cultural Connections, Collections, and Reflections

In the talk, Humanity centred design: A promising approach for preparing culturally responsive educators, Catherine Lawless Frank and Treavor Bogard focused on using human centred design to foster a global mindset with the aim of enhancing culturally responsive teaching. The key idea here is that to be effective educators, teachers must understand their own culture and that of their students, since culture and education are intertwined. Human centred design (HCD), they explained, is a framework for empathetic immersion into a social problem in order to adjust one’s thinking based on experiential knowledge of the culture and needs of those affected. In a true HCD framework, the desire to enhance a global mindset originates within an individual, who feels uncertainty or tension regarding their understanding. Two HCD projects were highlighted, the first involving collecting books to serve local neighbourhood needs, and the second involving assigning students grocery store visits in different neighbourhoods.

In the closing plenary, Steve Harmon spoke about future trends in his presentation entitled Creating the next in education: On the road to the university of 2040. He outlined some of the dramatic technological developments currently underway, including neural nets to allow brain-computer interfacing, and neurostimulation to improve learning capacity. AI capabilities are also growing exponentially, making it hard to predict future developments. Drivers of change include fewer high school graduates choosing to go to college, and the increasing diversity of student cohorts, as well as the changing nature of work (from globalisation to the gig economy) and needs and capabilities (the need for agile, T-shaped thinkers with 21st century skills). Current growth is in jobs requiring social skills (ideally in combination with maths skills) and in nonroutine cognitive jobs. The old higher education approach of information transfer is inadequate to this new era. There needs to be a focus on deliberate innovation and lifetime education, and universities need to serve as platforms rather than pipelines.

He went on to mention a number of future-oriented initiatives at Georgia Tech, including whole person education, covering: experiential learning, globalisation at home, professional development for graduate students, and a whole person curriculum. The T-shaped student, he said, should have both breadth of knowledge and depth of expertise. Adaptive expertise is more important than routine expertise. Another initiative is New products and services, with blockchain (essentially a distributed database) as one example that might be used in academic credentialling. A third is Advising for a new era, covering prescriptive advising (based on likely trends), intrusive advising (where students are at risk) and developmental advising, as well as personalised advising for a lifetime. A personal board of directors would advise students, and would include advisers on courses, content and careers. A fourth is AI and personalisation, covering AI-enabled personalised learning systems, along with AI-based, adaptive learning platforms for mastery learning, and human-centred AI. Students might well have a group of AIs to help them. A fifth is A distributed worldwide presence, which is about how to provide lightweight versions of the Georgia Tech presence in cities around the country with large concentrations of online students nearby. Fuller details are available in the report Deliberate Innovation, Lifetime Education.

All in all, this three-day conference provided a forum for rich pedagogical and cultural exchanges across disciplinary as well as geographical boundaries, allowing all of us to come away with new perspectives on how we teach and how our students learn.