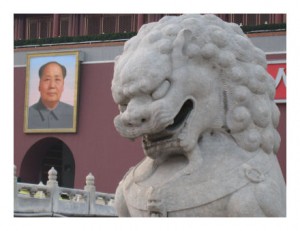

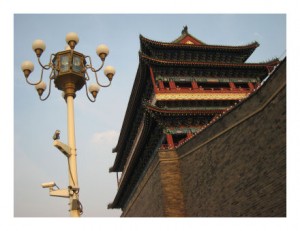

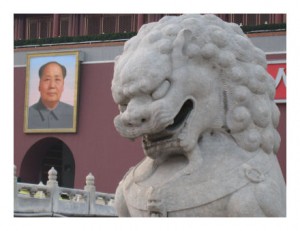

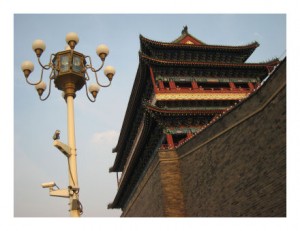

AILA 2011: The 16th World Congress of Applied Linguistics

Beijing, China

23-28 August, 2011

One of the major themes running through the 16th AILA Congress was the relationship of new technologies to language teaching. Over the course of six days, presenters from around the world discussed changing teacher training, changing teaching, and changing language – especially the growing importance of digital literacies.

One of the major themes running through the 16th AILA Congress was the relationship of new technologies to language teaching. Over the course of six days, presenters from around the world discussed changing teacher training, changing teaching, and changing language – especially the growing importance of digital literacies.

Changing teacher training

In their presentation Language teacher education: Developments in distance learning, David Hall and John Knox reported on an investigation into institutional, teacher and student views of LTED (Language Teacher Education by Distance). Those surveyed believed there are numerous advantages of LTED, including:

- flexibility/accessibility (approx. 70%)

- situated learning (approx. 23%) (in particular the theory/practice interface when teachers study while working)

- learner control

- diversity of the student cohort

- financial issues for students

- interaction & mediation of discourse (you can take time to respond, e.g., in asynchronous discussion)

- learner responsibility

- employability

In short, the old advantages of LTED remain (such as flexibility and situated learning), but new advantages (such as diversity of the cohort and mediation of discourse) are expanding as technology breaks down barriers of time and space. Hall and Knox argued that both face-to-face and distance learning have particular affordances and advantages that in some ways balance each other out.

In her paper The development of language teachers’ expertise in exploiting the interactive whiteboard towards a socio-cognitive approach to computer-assisted language learning, Euline Cutrim Schmid noted that there is some concern that interactive whiteboards (IWBs) can be used to enhance teachers’ control of the learning environment, thereby promoting more traditional transmission or behaviourist educational approaches.

According to Warschauer (2000: 57), a socio-cognitive approach to electronic language learning activities should:

- be learner-centred

- be based on authentic communication

- make some real difference in the world

- provide students with an opportunity to explore and express their evolving identity

The question is whether and how teachers can be encouraged to use IWBs to support this kind of approach. Cutrim Schmid presented a case study of a language teacher who moved from a teacher-dominated stage of IWB use where:

- the teacher focused mainly on form and controlled practice, and overgeneralised the use of the IWB to the whole lesson, doing most activities with a full-class focus (but she felt dissatisfied with students’ level of activity)

- the teacher delivered authentic multimedia-based input (but she realised that students’ fascination for multimedia materials didn’t necessarily correlate with effective language learning)

to a learner-centred stage where:

- students had an opportunity for co-construction of knowledge (where the equipment was not the main focus but was used as necessary to support language-based tasks, and where the IWB was used as a platform to show student-produced web 2.0 materials as well as being used by students themselves for presentations)

- students had an opportunity for self-expression

The teacher developed important CALL competencies as she came to understand the strengths and limitations of the technological options, and to make informed judgements on the suitability of the tool for the task.

Cutrim Schmid concluded that IWBs can present a threat to communicative language teaching, especially as the acquisition of new competencies doesn’t occur automatically. There is a real need for teacher development in this area, based on a sound theoretical basis and an examination of pedagogical practice.

In a talk entitled Web 2.0 for teaching and learning: Professional development through a community of practice model, Christina Gitsaki reported on a PD programme developed for English teachers in the UAE to help them integrate web 2.0 into their teaching within a laptop programme.

The results of an initial investigation had shown that teachers reported a high level of confidence with emailing, word processing, accessing a VLE, etc, but made little use of web 2.0 and were in fact concerned about students accessing web 2.0 on their laptops, especially social networking sites. Students reported that the activities they wanted to do with the laptops were very different from what teachers did with them – they wanted to engage in more creative and collaborative activities. In other words, the way teachers were using laptops in the classroom did not reflect students’ online socialising and learning in their own time.

A PD programme, underpinned by a community of practice model, was set up to give teachers greater awareness of web 2.0 and how to use it pedagogically. It was based on the following cycle of learning:

- Introduction to new idea

- Reflection & interaction

- Challenges & negotiation

- Outcome: Adopt, Adapt, Abandon

Tools covered in Semester 1 included Edmodo, Flickr, Google Docs, Mindmeister, MyPodcast, VoiceThread, Xtranormal and YouTube, and in Semester 2 they included Photopeach, Dipity, OurStory, Prezi, Glogster and Comic Life.

Teachers found the community of practice approach valuable. They learned about web 2.0 tools, tried them out, and collaborated with colleagues on how to use them in the classroom. The more confident teachers actually tried the tools with their students and were able to report to colleagues on their experience.

Changing language teaching

In his talk The impact of digital storytelling with blended learning on language teaching, Hiroyuki Obari argued that digital storytelling can improve student autonomy as well as proficiency in English. He observed that digital storytelling “merges the traditional art of storytelling with the power of new technologies” and can promote linguistic as well as paralinguistic skills in students. Through digital storytelling, students practise rhetorical skills as well as technological skills, with technology becoming an “imagination amplifier”. Assessment of students’ English following the introduction of digital storytelling into his classes resulted in improved scores, and most students agreed it was useful in learning EFL.

The symposium Computer-assisted language learning and the learner consisted of a number of papers (by Hayo Reinders and Sorada Wattana, Bin Zhou, Hiroyuki Obari, and Mirjam Hauck) examining the effects of CALL on student learning. In the presentation The effects of games on interaction and willingness to communicate in a foreign language, Hayo Reinders and Sorada Wattana argued that, given the positive effects of gaming on classroom interaction and language production, we should appropriate gaming software for pedagogical purposes (rather than the other way round). The paper concluded with the following recommendations:

- Do not let applied linguists mess up game design.

- Do build on existing non-educational games as ecologies in their own right.

- Do gather evidence of game language use and attitudes to learning.

- Do make links between formal and non-formal learning.

In his paper Students’ perspectives of an English-Chinese language exchange programme on a web 2.0 environment, Bin Zou described a web 2.0-based programme for learners of English in China and learners of Chinese in the UK. Wikispaces was the platform chosen for students in these two groups to interact with each other around topics of common interest. The History function of the wiki allowed students to easily identify corrections made to their texts by the native speakers of the target language, though some students preferred to upload Word documents containing the corrections. Overall, wikis were found to be a useful and motivating platform for language education.

In his paper Integration of technology in language teaching, Hiroyuki Obari argued that social learning is the key trend of coming years. Open Educational Resources, he suggested, will be a big part of it. He noted that mobile technologies can be used to support lessons in a number of ways; for example, announcements and information about words and phrases can be sent to language students on mobile devices while they are commuting. Digital storytelling, he suggested, is also a very useful tool which allows students to demonstrate creative thinking, construct knowledge, and develop innovative products. Social learning and blended learning, he concluded, can both help students improve English proficiency and IT skills, while fostering autonomous learning.

In her paper Promoting teachers’ and learners’ multiliteracy skills development through cross-institutional exchanges, delivered at a distance by Skype video, Mirjam Hauck reported on two empirical case studies of a task-based telecollaborative learning format. She argued that it is important for both teachers and learners to develop multimodal communicative competence, as defined by Royce (2002), and showed Elluminate as an example of a multimodal communicative environment. There is an “orchestration of meaning” in multiple modes online. It is important, she suggested, that language teachers design tasks that oblige learners to make use of multiple modalities online. She quoted Hampel and Hauck (2006) on the need to promote the kinds of literacy required to use new democratic learning spaces to their best effect.

Changing language: New literacies

In introducing the Digital futures symposium, David Barton suggested that literacy studies research is a good lens for looking at language and new technologies. In his own paper, Creating new global identities on the web through participation and deliberate learning, he stressed that literacy studies research sees literacy as a social practice. With the advent of web 2.0, there are new spaces for writing (with writing becoming more and more important), including multilingual writing. There are also new spaces for learning.

His paper focused in particular on the photosharing site Flickr. He suggested that a typical Flickr page involves a number of different writing spaces: textual description, discussion, tags, etc. He reported on a study of Flickr use conducted collaboratively with Carmen Lee. New multilingual encounters occur online – such as when a Chinese person learning English in Hong Kong discusses photography with Spanish speakers elsewhere in the world. Comments may be left on photos in different languages.

He noted that many Flickr users write about learning, even though it’s not predominantly a learning site. He spent some time discussing ‘Project 365’ (in which people take one photo a day for a year), where it is very noticeable that many people refer specifically to learning. These are, he suggested, “deliberate acts of learning”. He listed the following key characteristics of Project 365:

- it’s social

- deliberate acts of learning

- discourse of self-improvement

- it’s life-changing (people are not just learning about photography but about life; learning, he suggested, should be life-changing)

- vernacular theories of learning (where people present their own views of how learning takes place)

- reflexive writing spaces

- a passion (something, he argued, that is often left out of theories of learning)

My own paper was part of the symposium Enhancing online literacies: Knowledge and skills for language students and teachers in the digital age, organised by Regine Hampel and Ursula Stickler from the Open University. As part of this symposium, papers were delivered by myself, Linda Murphy, Aline Germain-Rutherford, Cynthia White, Hayo Reinders and Sorada Wattana, and Regine Hampel and Ursula Stickler. Paper summaries, reference lists and links can be found on the E-language Wiki.

In the opening paper, Digital tools and the future of literacy, I argued that our communication landscape has shifted dramatically in a few short years. New web 2.0 and related tools, ranging from blogs, wikis and podcasts to social sharing services, social networking sites and virtual worlds, are having an increasing impact on our everyday lives – and our everyday language and literacy practices. It’s more crucial than ever for language teaching to encompass a wide variety of literacies which go well beyond traditional print literacy.

I focused on four specific digital literacies of particular relevance to language teachers and students: multimodal (multimedia) literacy, information literacy, intercultural literacy, and remix literacy. I showed how language teachers can incorporate elements of each into their everyday classroom activities. I concluded that combining traditional print with multimodal, information, intercultural and remix literacies can make the language classroom much more dynamic – and much more relevant to our students’ future lives and future uses of language.

In her paper Tutor skills and qualities in blended learning: The learner’s view, Linda Murphy argued that the difference between distance learning and regular learning is breaking down, thanks to the arrival of new technologies. The top-ranking important skills for online language tutors, as viewed by students in a 2011 study conducted at the OU, were:

- native/near native speaker competence (due in part to a need for cultural input)

- teaching expertise in supporting grammar and pronunciation development

- strong emphasis on affective dimension: approachable, enthusiastic, encouraging, fostering group participation with confidence, catering for differing needs and styles

- well-organised, focused use of contact time

- competent IT users

- prompt responses and awareness of support systems

In a previous study conducted in 2008, IT skills had not been listed in the top five most important skills, but by 2011, 20% of respondents mentioned IT skills. The idea of IT also overlaid many of the other tutor skills mentioned in student comments. She concluded by suggesting that teaching online is not so much about adding to one’s repertoire as transforming one’s practice for the online context.

In her paper Preparing our students for the intercultural reality of today’s online learning spaces, Aline Germain-Rutherford focused on intercultural issues. She opened with a quote from Edgar Morin, who argues against inadequate, compartmentalised learning and in favour of learning “about the world as world” in its contextual, global, multidimensional and complex reality. She referred also to Reeder, Macfayden, Roche & Chase’s (2004) description of culture as ‘negotiated’ rather than ‘given’.

Our job as language teachers, she suggested, is to design learning environments where students can co-create linguistic and cultural content through their collaborative contributions to blogs, wikis and social networking platforms. She recommended Henderson’s (2007) model of E-learning Instructional Design, which is centred on epistemological pluralism and is designed to help raise students’ awareness of cultural diversity as they engage in co-construction of a learning space where multiple cultural contexts are made visible and debatable.

In her paper Online academic literacy within user-generated content communities: Connections and challenges, Cynthia White started with the new literacies position, which sees literacy as a social practice. There is of course a need to switch practices between different contexts. She referred to Kern (2006), who suggested that the internet has complexified the notion of literacy by introducing multimedia dimensions and altering traditional discourse.

She described a telecollaborative project involving students from Germany and New Zealand, where they interacted online, e.g. collaboratively writing on a wiki, as well as making use of tools like Facebook and YouTube which they themselves introduced. She explored how students practised language and negotiated meaning in examining the relationship between German and New Zealand/Maori culture. She finished with a number of questions, including:

- What are the dimensions of literacy as social practice in web 2.0 telecollaborative projects?

- What is the intersection between intercultural literacy and online literacy?

In the paper Incorporating computer games into the EFL classroom, Hayo Reinders and Sorada Wattana focused on gaming literacy and asked how, as teachers, we can move from an entertaining to an educational use of games. Key learning principles present in many games include:

- the active, critical learning principle (gaming environments are about active and critical, not passive, learning)

- the psychosocial moratorium principle (it’s OK to make mistakes and learn from them)

- the practice principle (learners get lots of practice which is not boring and where they experience ongoing success)

However, language learning through games is not yet well developed. Many online language games do not really exploit the capabilities of the digital medium, but essentially reproduce offline activities.

The paper reported on an experiment conducted in Thailand, where students were able to communicate in English in a copy of a commercial gaming environment. It was found that students had a greater willingness to communicate in online gaming than in the classroom. It was also found that students produced a greater quantity of language in the gaming environment compared to the face-to-face class.

In the concluding symposium presentation, Transforming teaching: New skills for online language learning spaces, Regine Hampel and Ursula Stickler focused on teachers and how they can transform the spaces that exist online into learning spaces. Referring to their previously developed skills pyramid for online language teachers, they pointed out that the two base layers have to be taken for granted nowadays, as teachers can’t operate online without them, but the higher level skills still need to be developed.

Some of the key literacies for students are:

- Basic literacy

- technical competence with software

- Multimodal literacy

- dealing with constraints and possibilities of the medium

- having basic IT competence

- Linguistic and inter-/multicultural literacy

- facilitating and developing communicative competence

- online socialisation

- Remix literacy

- own style

- creativity and choice

Online learning spaces allow:

- blending of environments – beyond time, space, and pace (making learning flexible)

- individualised learning (making learning relevant)

- authentic communication (making learning real)

- collaboration (making learning interactive)

- online telecollaboration (making learning multi/intercultural)

- creativity and choice (making learning fun)

Of course, as they stressed, there is still a need for negotiation of a number of aspects of learning spaces. Future developments, they suggested, should include the development of new pedagogies; online communities of practice; institutional training; and curriculum planning.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Overall, the AILA Conference provided lots of food for thought for anyone working in the overlapping areas of language teaching and new technologies. It will be interesting to see how both teaching and technologies have continued to develop when the 17th AILA Congress takes place in Brisbane in 2014. Watch this space …

Once again this year, the largest TESOL conference in Australia saw a number of sessions on CALL and e-learning, especially the use of Web 2.0 technologies.

Once again this year, the largest TESOL conference in Australia saw a number of sessions on CALL and e-learning, especially the use of Web 2.0 technologies.