eLearning Forum Asia

29th – 31st May, 2013

Hong Kong

The eLearning Forum Asia 2013 was held at Hong Kong Baptist University with a record-breaking number of attendees. It’s clear that digitally mediated learning is taking off in this part of the world. This conference will be one to watch as it grows in size over years to come.

Richard Armour, from the Hong Kong University Grants Committee (UGC), opened the conference with a discussion of Hong Kong’s “3+3+4” Curriculum and the opportunities for e-learning presented by the new 4-year undergraduate university curriculum. This change, he suggested, is contextualised by the shift towards a knowledge-based economy, enabling students to further develop their language abilities, knowledge base, critical thinking and independence. There is a core general curriculum, with more specialisation as students advance. The curriculum is designed to be more student-centric and allow for whole-person development. The UGC has acquired government funding to promote pedagogical change and innovation in areas such as blended learning, curriculum development, and learning environments. This funding will be project-based. Key questions are what e-learning can bring to the additional year, general education, the common core, sharing specialities across universities, or to achieve a paradigm shift.

Karl Engkvist from Pearson gave a keynote presentation entitled Preparing for the coming avalanche, making reference to the recent publication by Michael Barber, Katelyn Donnelly and Saad Rizvi. He mentioned that globalisation and technology are transforming education; there is greater competition for students and research funding; high-quality educational content is accessible online for free; and the functions of higher education are being supplied by non-academic providers. The 20th century university paradigm is under pressure: knowledge is ubiquitous and free, so it needs to be curated effectively; public funding is being replaced by private funding; students can shop globally for an education; the pace of workplace innovation is accelerating; and graduate unemployment is high, but employers can’t find qualified candidates. We need to more closely link education with future workplace needs. Students, as consumers, may come to expect more tangible outcomes from their education.

He listed a number of signs of change in the educational situation. MOOCs are disrupting education by giving huge numbers of students access to elite education. There are also non-university providers like StraighterLine 2U, alternatives like Thiel Fellowships, complementary options like General Assemb.ly, the Mozilla Foundation’s idea of badging, and the notion of third stage careers catered to, for example, by the Korean National Open University. He suggested that new models of education are improving quality, increasing market share and lowering cost – the way new competitors traditionally unseat complacent incumbents. Traditional universities, too, are being unbundled. Cities are seeing higher education institutions as powerhouses of their economies. Faculty can teach from anywhere – and they don’t have to be academics. Students, too, can learn from anywhere. Curriculum has become a commodity. E-learning can offer much more flexibility in this space. Deep, radical, urgent transformation – not just incremental change – is necessary.

He went on to talk about The Learning Curve, a Pearson report and website that compare different educational systems around the world. Innovative systems have to value and fund stronger student outcomes; value accountability – setting clear goals and expectations; be future oriented – focusing on skills necessary for the future; and attract and continuously train good teachers. But there are big differences, too: the two most ‘successful’ educational systems, Korea and Finland, share almost nothing in common. In Korea, the top quartile outperforms everyone in the world, but the lowest quartile doesn’t do well at all; in Finland, the two middle quartiles outperform everyone in the world, but the top quartile doesn’t do as well comparatively. This raises philosophical questions about what you want to achieve through an educational system.

In her keynote presentation, Kathy Takayama spoke about Integrative paths in the social construction of understanding. She discussed the need to prepare students for total engagement, applying conceptual understanding, and diving into unfamiliar territory – which are difficult-to-measure outcomes. Metrics which show that teachers have been effective include students taking ownership of their own learning; applying themselves through incremental, experiential learning; being comfortable with uncertainty; integrating insights from across the disciplines to solve problems; and developing adaptive expertise. She went on to say that expert thinking, which involves chunking of information (a kind of pattern recognition based on long experience), sometimes gets in the way. This is one reason why there’s a pressing need for development of faculty, who are fixed on the ways that things have always worked. Interdisciplinary entry points are important.

Brown University is experimenting with blended courses and flipped classrooms. She described an economics course, where one third of the traditional 50-minute lectures have been replaced with 10-minute vodcasts; the rest were retained in order to maintain instructor presence, which is important for the student experience. Students then got together in a classroom where they worked on solving problems collaboratively, facilitated by teaching assistants. Students gave feedback on the microlectures to indicate whether they did or didn’t cover what they needed to know; their feedback also indicated that instructor presence is important. When thinking about e-learning, we have to bring students in as creative partners.

She went on to discuss what old brick-and-mortar institutions need to think about with respect to MOOCs. This requires thinking through the process of deconstruction and reconstruction. Compartmentalisation is an issue, because the material has to be broken up into 10-min chunks. It’s also important to consider how you make connections between all these materials. Students will in fact create their own learning environments through social media and other channels. So MOOCs must be a part of an overall shift in the direction of more social learning. We need to think about the pedagogies that support social learning, and how we might construct our courses differently.

In my own keynote presentation, which opened the second day of the conference, I spoke on Mobile outcomes: Improving language and literacy across Asia. I began by exploring both the affordability and affordances of mobile technologies for the teaching and learning of language and literacy, and looked at the kinds of learning contexts where mobile devices can play a role. I went on to consider the learning outcomes achieved with mobile devices. Assessment and feedback can both be enhanced by mobile devices. However, while there is considerable promise for the recording, monitoring and evaluation of learning in mobile projects, and especially for the deployment of learning analytics, this promise is often unrealised for a variety of practical and pedagogical reasons. On the one hand, we need to seek more hard data on improved learning outcomes in mobile projects; and on the other hand, we may need to consider the notion of outcomes more broadly, including soft outcomes like the acquisition of 21st century skills and digital literacies. I concluded by looking at three mini-case studies of mobile language and literacy interventions from Pakistan, China and Singapore, asking in each case what evidence we can see of improved hard and soft outcomes, and what we can learn for future projects.

In her plenary, Hart Wilson spoke about Moodle magic: Unleashing Moodle’s potential. She outlined the many features of Moodle which, along with ease of integration with other software, can help support and organise teaching and learning. She suggested a number of useful activities, including getting students to send in questions ahead of class to shape a class (Online Text feature), or getting students to engage in peer review (Workshop feature). She suggested that Moodle’s tools allow us to think differently about teaching, and it serves as a platform to connect students to content, students to students, and students to instructors. This paper was followed up by a half-day workshop the next day, where the uses of Moodle were explored in much more detail.

Jie Lu and Tianchong Wang, two graduate students working with Daniel Churchill, gave a paper called Exploring the educational affordances of the current mobile technologies: Case studies in university teachers’ and students’ perspectives. They spoke about two case studies. The first took as its starting point Daniel Churchill’s (2005) work on teachers’ private theories, six of which impact on their design and technology integration decisions. Key factors which positively influenced teachers’ use of technology were revealed to be: size (a smartphone screen may be too small; a laptop may be too heavy; but an iPad balances these points); mobile ergonomics; instant boot up; battery life; ease of use; touch sensitivity; apps; access to resources; and sharing and interaction to support a more student-centred teaching paradigm. Issues for teachers included: document format compatibility; connecting to a classroom projector; file management & syncing; inputting text on a touch screen; students’ ownership of tablets; and the idea of a “technology dance” (is the technology supporting teaching or a goal in itself?).

The second case study focused on students’ use and perceptions of mobile technologies as learning tools. Their use of mobile devices to support their learning was generally quite limited: tracking what was going on in online learning environments; keeping in contact with other group members; and reviewing learning materials uploaded by the teacher anywhere and anytime. Issues for students included: limited wifi coverage; inconvenient input options; lack of learning materials tailored for smartphones or tablets, and inability to play Flash materials.

Pao Ta Yu gave a plenary paper entitled How to design massive qualified digital contents both for online and classroom learnings. He spoke about MOOCs, indicating that they combine multimedia and cloud technology with lectures to create more energy around e-learning. They may be combined with social networking and social media sites, using the latter as a content delivery area. Most students who enrol in MOOCs are currently professionals rather than college students, though this may shift as models are developed for integrating MOOCs into students’ educational pathways. The biggest short-term impact of MOOCs may in fact be legitimisation of online and hybrid learning.

He went on to speak about flipped classrooms, whose advantage, he suggested, is to “take the snooze out of the classroom”. They can individualise classroom learning time for students, allow students to review lessons at their own pace, and break the regular classroom rhythm. Flipped materials should be simple, interesting, and meaningful, he suggested. He suggested that microvideos will be created by teachers to produce a lot of cloud digital content. This process can integrate with the flipped classroom model. Rapid design, high quality recordings, and easy uploading and downloading, will be important for future mobile learning.

Diana Laurillard wrapped up the conference with her closing keynote Teaching as a design science: Designing and assessing the effectiveness of the pedagogy in learning technologies. She spoke about government policies from around the world which stress that teachers need to design and deliver ICT-enhanced education, and to undertake professional development. UNESCO is developing new post-2015 goals for education, including a full 9 years of basic education. Higher education demand is expected to double over coming years. This will have major implications for teacher training. How can higher education nurture individual teachers while reducing the 25:1 student: staff ratio, i.e., beginning to operate on a mass scale?

She explored MOOCs as one possible answer, using a Duke credit-bearing MOOC as an example. Many students already had educational qualifications and study experience. There was a very large attrition rate, and often in MOOCs there are only a couple of hundred people who complete a course – much like regular online teaching. While many MOOCs offer only peer support, the Duke MOOC included tutored discussions and assessment, which is time-consuming for support, and worked out at a student: staff ratio of around 20:1. If this kind of support is provided, the demands on staff time will increase as the number of students increases. Only a basic MOOC, without tutor support, can scale at no extra cost.

We need to understand the pedagogical benefits and teacher time costs for online HE. What are the new digital pedagogies that will address the 25:1 student support conundrum? Who will innovate, test, and build the evidence for what works online? It can only be teachers. It may be that we should revisit and rework some old approaches. Pedagogies for supporting large classes might include:

- Concealed multiple choice questions (possible answers are revealed after students have written their own suggested responses);

- The virtual Keller Plan (introduce content > self-paced practice > tutor-marked test > student becomes tutor for credit, until by the end half the class is tutoring the rest);

- The vicarious master class (run a tutorial for 5 representative students; questions and guidance represent all students’ needs);

- Pyramid discussion groups (240 individual students produce an answer to an open question, then there is a joint response from pairs, then groups of four, etc, until the teacher receives only six responses to comment on in detail).

Collecting big data in line with Laurillard’s Conversational Framework might allow us to better focus on exactly what to collect and how to apply learning analytics. We could consider what is accessed in what sequence, the questions asked, social interaction patterns, tracked group outputs, peer assessment, tracked inputs, reaction times, analysis of essay content, quiz scores, game scores, and accuracy of models.

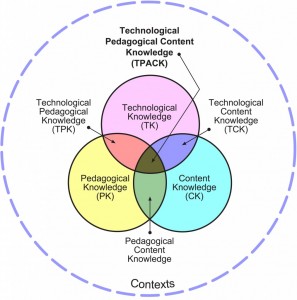

Teachers as designers need the tools for innovation. She mentioned the PPC (Pedagogical Pattern Collector) browser where you can find pedagogical patterns created by others, tied to particular learning outcomes, and adapt them to your own context and needs. This system creates a way of sharing ideas between individual teachers, across disciplinary boundaries, and between institutions. To meet the upcoming demand, teachers need to work more like scientists who build on and refine each other’s work. The PPC gives them the tools to do this. This supports a cycle of professional collaboration. As a computational model, it also allows us to work out the consequences in terms of the pedagogical benefits, and the comparative costs of teachers’ workloads, depending on the cost of initial setup and the cost of ongoing support. It also allows us to compare conventional and blended learning to see whether there is, for example, less emphasis on acquisition and more emphasis on discussion. It’s important to invest in teachers who can innovate in learning technologies.

The global demand for HE requires investment in pedagogic innovation to deliver high quality at scale. Technology-based pedagogical innovation must support students at a better than 25:1 student: staff ratio. Teachers need the tools to design, test, gather the evidence of what works, and model benefits and costs. Teachers are the engines of innovation – designing, testing, and sharing their best pedagogic ideas.

Overall, the quality of the papers, the quantity of attendees, and the general buzz around the conference are a sign that e-learning is very much coming of age in Asia. Next year’s event in Taiwan will carry on the eLearning Forum tradition.

Amongst a diverse set of themes, the 2010 English Australia Conference included a technology strand with a strong focus on the initial implementation of technology in TESOL contexts and, in particular, how to approach teacher training.

Amongst a diverse set of themes, the 2010 English Australia Conference included a technology strand with a strong focus on the initial implementation of technology in TESOL contexts and, in particular, how to approach teacher training.