ICDE World Conference on Online Learning

Toronto, Canada

16-19 October 2017

The ICDE World Conference on Online Learning, focusing on the theme of “Teaching in a Digital Age – Re-thinking Teaching and Learning”, took place over four days in October, 2017. Like at other recent large technology conferences, it was interesting to see increasing recognition of the broader sociopolitical and sociocultural questions in which online learning is embedded, as reflected in many of the presentations. Papers were presented for the most part in groups of three or four under overarching strands. Short presentation times somewhat restricted the content that speakers were able to cover, but each set of papers was followed by audience discussion where key points could be elaborated on.

In his plenary presentation, edu@2035: Big shifts are coming, Richard Katz referred to Marshall McLuhan’s comment that “we march backwards into the future“, meaning that it is very difficult for us to predict the future without using the past as a framework. He went on to speak of Thomas Friedman’s framework for the future involving six core strategies – analyze, optimize, prophesize, customize, digitize and automize – in which, Katz suggested, all companies as well as all educational institutions need to be engaged. He suggested we may need to consider wild scenarios: could admission to colleges in the future be based not on performance tests but on genotyping? The gap between technology advancement and socialisation of technologies is widening, he stated.

As we look to the future, we have some choices in post-secondary education: avoid the topic; paralysis by analysis; choose mindful incrementalism; or invent a new future. To do the last of these, we need to take at least part of our attention off the rear view mirror. We need to construct scenarios, develop models, identify risks, and extract themes, and to present these ideas in short video formats that will be engaged with by today’s audiences. In short, we need to iterate, communicate and engage.

He mentioned William Gibson’s comment that “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed“, and a comment from Barry Chudakov (Sertain Research) that “algorithms are the new arbiters of human decision-making“. Evidence that the future is now can be found in various areas, from chatbots to the explosion of investment in cognitive systems and artificial intelligence (AI). Drawing on Pew Internet research, he suggested algorithms will continue to proliferate, with good things lying ahead. However, humanity and human judgement are lost when data and predictive modelling become paramount. Biases exist in algorithmically organised systems, and algorithmic categorisations deepen divides. Unemployment will rise. And the need is growing for algorithmic literacy, transparency and oversight.

He asked whether, by 2035, we can use new technologies and algorithms to personalise instruction in ways that both lower costs and foster engagement, persistence, retention and successful learning, possibly on a global scale? He concluded with a number of key points:

- The robots are coming, aka change is inevitable;

- Our mission must endure (even as our delivery and business models change);

- While the past may be a prologue, there will be new winners and losers;

- A future alma mater may be Apple, Google, Microsoft, Alibaba …;

- scale is critical;

- lifetime employability is critical;

- students will determine winners and losers;

- The future is already here, the question is whether we can face it;

- ‘extreme planning’ must be practised;

- Never discount post-secondary education.

In his plenary presentation, Reboot. Remake. Re-imagine, John Baker, the CEO of D2L, asked why it is that so many movie makers decide to re-imagine old movies? It’s because the original idea was great, but something has changed in the meantime, and a new direction is needed. Today’s political, science and environmental problems will ultimately be solved through education and its ripple effects, he suggested. In the current climate of rapid change, it is essential to focus not on remaking or rebooting, but rather on re-imagining the possible shape of education.

The technology must be about more than convenience; it must improve learning and increase engagement and satisfaction. Well-designed learning software can allow teachers to reach every student; what if there was no back of the classroom, he asked. It should be possible to reach remote learners or disabled learners or refugees or students using a range of devices from the brand new to hand-me-down technologies (hence the importance of responsive design).

We will soon see AI, machine learning, automation and adaptive learning becoming important; it is not just technology that is changing, but pedagogy. He cited an Oxford University study suggesting that 47% of all current jobs will cease to exist within two decades as a result of the advent of AI. The reality is that our skills development is not currently keeping pace with what will be needed in an AI-enabled future. Continuing educational opportunities for the workforce will be key here.

He suggested that the most important pedagogical innovation of the current era is competency-based education. In a discussion of its advantages, especially when accelerated by adaptive learning, he indicated that the greatest benefit is not so much the achievement of the competencies, but the leftover time and what can be done with it – could students learn more about other areas? Could they enrich their education through more research even at undergraduate level?

In response to an audience question, he also suggested that ‘learning management system’ (LMS) is an outdated term and ‘learning platform’ or ‘learning hub’ might be preferable. How do we capture and share the learning that is taking place across multiple platforms and spaces? It is vital that these systems should be porous, and interoperability between systems (e.g., through Learning Tools Interoperability [LTI] and Caliper) is essential.

In his plenary presentation, The future of learning management systems: Development, innovation and change, Phil Hill suggested that while there are many exciting educational technology developments, there is also a great deal of unhelpful hype about them. The steady, slower paced progress being made at institutions – for example in the introduction of online courses – is in many ways disconnected from the media and other hype. What is important is what can be done with asynchronous, individualised online education that cannot be done so easily in a plenary face-to-face classroom. Some of today’s most creative courses are bypassing LMSs in order to incorporate a wider range of platforms and tools.

Most institutions now have an LMS; these are seen as necessary but not exciting or dynamic. The core management system design is based on an old model. Some companies are trying to add innovative features, but it’s not clear how useful or effective some of these may be. (It may be that over time all ed tech platforms start adding in extra features which eventually make them look like badly-designed LMSs.) When LMSs first appeared, there were few competitors, but now there are many flexible platforms available, creating a demand that LMSs can replicate the same features. There is considerable frustration with LMSs, which are seen as much harder to use than the platforms and tools on the wider web.

He mentioned that in higher education Moodle is currently the LMS with the largest user base, while Canvas is the fastest growing LMS. At school level, Google Classroom, Schoology and Edmodo have some leverage, but they are less used in higher education. Many other platforms have attempted to enter the mainstream but have since disappeared. Overall, this is a fairly static market without many new successful entrants. The trend is towards having these systems hosted in the cloud; this may be the only choice with some LMSs, such as Canvas. While there is currently a lot of movement towards open education, in North America the installed base of LMSs is moving away from the main open source providers, Moodle and Sakai; similar trends are seen elsewhere. There is a certain perception that these look less professional than the proprietary systems. Open source is arguably not as important as it used to be; many educational institutions have moved away from their original concern not to be beholden to commercial providers, and are now focusing more on whether staff and students are happy with the system. Worldwide we’re seeing most institutions working with the same small number of LMSs: Canvas, D2L, Blackboard, Moodle and to some extent Sakai. We should consider the implications of this.

The question is how to resolve the tension between faculty desires to use the proliferating educational technologies which offer lots of flexible teaching and learning options, and institutional insistence that faculty make use of the LMS. Many people are saying that LMSs should go away, but in fact that’s not what we’re seeing happening. Opposition to LMSs is largely based on the fact that they function as walled gardens, which is how they were originally designed. In many cases, they have added poor versions of external software like blogs or social networks, and there has been an overall bloating of the systems.

What we’re seeing now is a breaking down of the walled garden model. The purpose of an LMS is coming to be seen as providing the basics, with gateways offered so that there are pathways to the use of external tools. It should be easy to access and integrate these external tools when faculty wish to use them. Interoperability of tools through systems like LTI, xAPI and Caliper is an important direction of development, though there is a need for these standards to evolve. They key point however is the acceptance by the industry that this is the direction of evolution. He concluded that there are three major trends in LMSs nowadays: cloud hosting; less cluttered, more intuitive designs; and an ability to integrate third-party software. Much of this change has been inspired by the Educause work on NGDLEs. There is a gradual move among LMS providers towards responsive designs so that LMSs can be used more effectively on mobile devices.

The strand Engaging online learners focused on improving learning outcomes through improving learner engagement. In their presentation, Engaging online students by fostering a community of practice, Robert Kershaw and Patricia Lychak explained their belief that if facilitators are engaged with developing their own competencies, then they will use these to engage students. Initially, a small number of workshops and informal support were provided for online facilitators in their institution; then a training specialist was brought in; and it was found through applied research that online facilitators wanted more development in student engagement, supporting student success, and technology use. A community of practice model with several stages has been developed: onboarding (involving web materials, a handbook, and a discussion forum) > community building (involving a discussion forum, webinars, and in-person events) > coaching (involving checking in with new facilitators, one-on-one support, and inquiries) > student success initiatives (involving early check-ins with students, mid-term progress reports on students, and final grade entry) > training (shaped in part by feedback from the earlier stages; this also shapes the next onboarding phase). Lessons learned include:

- introduce variety (delivery method, timing, detail level);

- encourage sharing (best practices, student success stories, sample report comments);

- promote efficiency (pre-populate templates, convert documents to PDF fillable forms, highlight LMS time-saving tools).

What the trainers try to do is to model for online facilitators what they can do for and with their students.

In his presentation, Chasing the dream: The engaged learner, Dan Piedra indicated that the tools we invest in can lock us into design mode templates. He quoted Sean Michael Morris: “today most students of online courses are more users than learners … the majority of online learning basically asks humans to behave like machines“. Drawing on Coates (2007), he suggested that engagement involves:

- active learning;

- collaborative learning;

- participation in challenging academic activities;

- formative communication with academic staff, and involvement in enriching educational experiences;

- feeling legitimated/supported by learning communities;

- work-integrated learning.

He showed a model being used at McMaster University involving the company Riipen, which places a student with a partner company that assesses students’ skills, after which the professor assigns a grade.

In her talk, A constructivist pedagogy: Shifting from active to engaged learning, Cheryl Oyer referred to Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s Community of Inquiry model involving cognitive, teaching and social presence. She mentioned a series of learner engagement strategies for nursing students: simulations, gamification, excursions, badges and portfolios.

The strand Online language learning focused on the many possibilities for promoting language learning through digital technologies. In his presentation, The language laboratory with a global reach, Michael Dabrowski talked about a Spanish OER Initiative at Athabasca University. The textbook was digitised, with the Moodle LMS being used as the publishing platform. Open technologies were used, including Google Maps (as a venue for students to conduct self-directed sociocultural investigations), Google Translate (as a dictionary, and a pronunciation and listening tool, which now also incorporates Word Lens for mobile translation), and Google Voice (the foundation for an objective open pronunciation tutor). With Google Translate, there are some risks including laziness with translation and uncritical acceptance of translations, but in fact it was found that students were noticing errors in Google’s translations. With Google Voice, it is not a perfect pronunciation tutor; sometimes it is too critical, and sometimes too forgiving. Voice recognition by a computer is nevertheless a preferable form of feedback compared to learners’ own self-comparisons with language speakers heard in an audio laboratory; effectively it is possible to have a free open mobile language learning laboratory nowadays.

In her presentation, Open languages – Open online learning communities for better opportunities, Joerdis Weilandt described an open German learning course she has run on the free Finnish Eliademy platform. In setting up this course, it was important to transition from closed to open resources so they could be modified as needed. Interactive elements were added to the materials presented to students using the H5P software.

In their paper, Language learning MOOCs: Classifying approaches to learning, Mairéad Nic Giolla Mhichíl and Elaine Berne explained that there has been a significant increase in the availability of LMOOCs (language learning MOOCs). They were able to identify 105 LMOOCs in 2017, and used Grainne Conole’s 12-dimension MOOC classification to present an analysis of these (to be published in a forthcoming EuroCALL publication). They went on to speak about a MOOC they have created on the FutureLearn platform to promote the learning of Irish.

In his presentation, Online learning: The case of migrants learning French in Quebec, Simon Collin suggested that linguistic integration is important in supporting social and professional integration. This has traditionally been done face-to-face but increasingly it is being done online. Advantages of online courses for migrants fall into two major categories: they can anticipate their linguistic integration before arriving; and after migration, they can take online courses to facilitate a work-family-language learning balance. He described a questionnaire about perceptions of online learning answered by 1,361 adult migrants in Quebec. The common pattern was to take an online course before arrival, and then a face-to-face course after arrival. Respondents thought online courses were more helpful for developing reading and listening, but not as helpful for developing speaking skills.

The strand Leveraging learning analytics for students, faculty and institutions brought together papers focusing on the highly topical area of learning analytics. In their paper, Implementing learning analytics in higher education: A review of the literature and user perceptions, Nobuko Fujita and Ashlyne O’Neil indicated that there are benefits of learning analytics for educators in terms of improving courses and teaching, and for students in terms of improving their own learning. They reported on a study of perceptions of learning analytics by educators, administrators and students. Overall, there was a concern with the impact on students; the main concerns reported included profiling students, duty to respond, data security and consent.

In her presentation, An examination of active learning designs and the analytics of student engagement, Leni Casimiro indicated that active learning has four main components: experiential, interactive, reflective, and deep (higher-order). She reported on a study making use of learning analytics to determine to what extent students were in fact engaged in active learning. Descriptive analytics revealed that among the three courses examined, there was considerable variation in levels of activity; this was due to differences in student outcomes (tasks should help students focus rather than distracting them), teacher participation (teacher presence is essential), interactivity (teacher participation is important, as is the quality of questions), and the nature of students (asynchronous communication may be preferred by international students). Because of the weight given to teacher participation in active learning, it deserves special attention.

In his presentation, Formative analytics: Improving online course learning continuously, Shunping Wei explained that formative analytics are focused on supporting the learner to reflect on what has been learned, what can be improved, which goals can be achieved, and how to move forward. Formative analytics reports should be provided not only to management, but to teachers. It is possible to track whether students access all parts of an online course and whether they do so often, which would likely be signs of a good learner. It is also possible to create a radar map for a certain person or group, comparing their performance with the average.

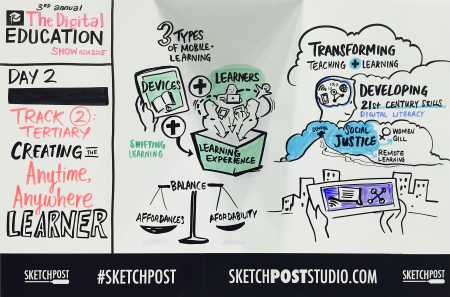

The strand Mobile learning: Learning anytime, anywhere brought together a number of different perspectives on m-learning. In their presentation, Design principles for an innovative learner-determined mobile learning solution for adult literacy, Aga Palalas and Norine Wark spoke about their project focusing on a literacy uplift solution in the context of surprisingly low adult literacy rates in Canada. They have created a cross-platform mobile app for formal and informal learning incorporating gamification elements within a constructivist framework, but with more traditional behaviourist components as well. Based on data obtained in their study to date, key design themes and principles have been determined as follows:

- mobility: design for the mobile learner;

- learner-determined: respond to the learner;

- context: integrate environmental influences.

Future plans include presentation of the pedagogical and technological principles and guidelines, and replication of the study in different contexts.

In her presentation, English to go: A critical analysis of apps for language learning, Heather Lotherington suggested that there is an element of technological determinism in mobile-assisted language learning (MALL). In MALL, there can be an app-only/content-oriented approach which gives you a course-in-a-box; or design-oriented learning which uses the affordances of mobile technologies in customised learning. Examining the most popular commercial language learning apps, she found that most were underpinned by ‘zombie pedagogies’ involving grammar-translation, audiolingualism, teaching by testing, drill and kill, decontextualised vocabulary, and so on. Ultimately, there were multiple flaws in theory, pedagogy, and practice. This led to failures from the point of view of mobility (with a need to record language in a quiet room rather than in everyday settings), gamification, and language teaching (there was, for example, generally a 4-skills model of language learning, which is outdated in an era of multimodal communication). Companies are also gathering users’ data for their own purposes. It is essential, she concluded, that language teachers are involved in designing contemporary approaches to mobile language learning; and teachers should also be familiar with content-based apps so they can incorporate them strategically in design-based language teaching and avoid technological determinism. Later, in question time, she went on to suggest that what we are currently confronted with is a difficult interface between slow scholarship and fast marketing.

In her presentation, New delivery tool for mobile learning: WeChat for informal learning, Rongrong Fan explained that WeChat has taken over from QQ as the most popular messaging platform in China. WeChat incorporates instant messaging, official accounts, and ‘moments’ (this works on the same principle as sharing materials on Facebook). Some institutions are using official accounts which push learning material to students, which could be as little as a word a day; an advantage is that this can support bite-sized learning, but a disadvantage is that too many subscriptions can lead to ‘attention theft’. WeChat can be used for live broadcasting with low fees; this allows more direct interaction but the long-term learning effects and value are questionable. It is also possible to set up virtual learning communities in the form of WeChat groups; this can be motivating and help to overcome geographical barriers, but learners may not be making real progress if they are learning only from each other. She concluded that WeChat can be integrated into formal learning as a complementary platform; that use of WeChat could be incorporated in teacher training to give teachers more options for delivering their content; and that a strong learner support team is needed.

The strand Virtual reality and simulation in fact covered both virtual and augmented reality. In his presentation, Flipping a university for a global presence with mirrored reality, Michael Mathews spoke about the Global Learning Center at Oral Roberts University. Augmented and virtual reality, he said, are additive to the experience that students receive, and can help us reach the highest level of Creating in Bloom’s Taxonomy. The concept of mirrored reality brings together augmented and virtual reality. These technologies can offer ways of reaching a diverse range of students scattered around the world.

In my own presentation, Taking learning to the streets: The potential and reality of mobile gamified language learning, which also formed part of this strand, I outlined the value of an augmented reality approach for helping students to engage with authentic language learning experiences in everyday life.

The strand Augmented reality: Aspects of use in education highlighted a range of contemporary uses of AR. In their talk, Distributed augmented reality training to develop skills at a distance, Mohamed Ally and Norine Wark described AR as an innovative solution to rapidly evolving learning needs. They spoke of their research on an industrial training package about valve repair and maintenance created by Scope AR and delivered onsite via iPads and AR glasses, for which they gathered data relating to the first three levels of the Kirkpatrick Model. The response to the AR training was overwhelmingly positive, with past hands-on training being seen as second-best, and computer-based training being least valued. It was felt that AR could replace lengthy training programmes. Scope AR has now developed a Remote AR collaboration tool which can be used to deliver support at a distance. The presenters concluded by saying that AR could have many applications in distance education where the expert is in one location but can communicate at a distance to tutor or train someone in a different location.

In his presentation, Augmented reality and technical lab training using HoloLens, Angelo Cosco explained that skilled trades training can be created to be accessed via Microsoft’s HoloLens, allowing students to learn at their own pace, but also offering development opportunities for employees. Advantages include the fact that unlike with VR, there are no issues with nausea; users can wear the HoloLens and move around easily; and recordings can be made and sent immediately through wifi networks.

In their paper, Maximizing learner engagement and skill development through modelling, immersion and gameplay, Naza Djafarova and Leonora Zefi demonstrated a training game (though not an AR game per se) for community nurses in the Therapeutic Communication and Mental Health Assessment Demo video. The game is set up on a choose-your-own-adventure model, giving students a chance to practice what they have learned in a simulated and ‘safe’ environment, which is especially valuable given the lack of practicum placement positions available. Usability testing was conducted to identify benefits and determine possible future improvements. Students felt that the game helped them to build confidence and evoked empathy, and added that they were very engaged. They thought that the purpose of the resource should be explained up front, and requested more instructions on how to play the game, as well as an alternative to scoring. The research team’s current focus is on how to facilitate game design in multidisciplinary teams, and on examining linkages between learning objectives and game mechanics.

While many of the talks described above already began addressing the bigger philosophical issues around digital learning, there were also strands dedicated to these larger questions. The strand Ethical issues in online learning brought together presentations addressing a wide range of ethical issues connected with digital learning. In his presentation, Privacy-preserving learning analytics, Vassilios Verykios noted that we all create a unique social genome through the many activities we engage in online. There is now an unprecedented power to analyse big data for the benefit of society; there can be improvement in daily lives, and verification of research results and reductions in the costs of research projects, but strict privacy controls are needed. There are some regulatory frameworks already in place to protect data, including the US HIPAA and FERPA and the EU Data Protection Directive and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The last of these deals with consent, data governance, auditing, and transparency regarding data breaches. There are data ownership issues, given that companies collect data for their own benefit; from a research perspective, it is important to remember that data is gathered by different bodies with their own ways of managing and storing it.

When it comes to educational data, technology now allows us to monitor students’ activities. Learning analytics is used to improve the educational system as a whole, but also to personalise the teaching of students. ‘Data protection’ involves protecting data so it cannot be accessed by intruders; and ‘data confidentiality’ means data can be accessed by legally authorised individuals. Data de-identification is a way of stripping out individually identifying characteristics from the data collected; one approach to anonymised data is known as k-anonymity. A fundamental challenge comes from the fact that when we anonymise data we do lose a lot of information, and it may somewhat change the statistics; so it is necessary to find a balance between accessing useful data and protecting privacy.

In his presentation, The ethics of not contributing to digital addiction in a distance education environment, Brad Huddleston indicated that addiction takes place in the same part of the brain, regardless of what you are addicted to. Addiction is about going harder to generate larger quantities of dopamine to overcome the chemical barrier erected by the brain to deflect excessive amounts of dopamine. When it comes digital addiction, the symptoms are: anger when devices are taken away; anxiety disorders; and boredom (the last of these results from a lack of dopamine getting through the brain’s dopamine barrier). Studies have suggested, amongst other things, that computers do not necessarily improve education; that reading online is less effective than reading offline; and that one of the most popular educational games in the world, Minecraft, is also one of the most addictive.

There is a place, he stated, for the analogue to be re-integrated into education, though not to the exclusion of the digital. We should work within the limitations of the brain for each age group; that means less technology use at lower ages. We should teach students what mono-tasking or uni-tasking is about. We also need to understand, he said, that digital educational content is just as addictive as non-educational content.

In her presentation, ‘Troubling’ notions of inclusion and exclusion in open distance and e-learning: An exploration, Jeanette Botha mentioned that the divide between developed and developing nations is increasing, largely because of a lack of internet access in the latter. In the global north, there has traditionally been a concern with equity, participation and profit. In the global south, there has been more of an emphasis on social justice, equity and redress; social justice incorporates the notion of social inclusion. Inclusivity, she went on to say, now has a moral, and by extension, ethical imperative.

Since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, there has been a focus on the inclusiveness of education. Open and distance learning are seen as a key social justice and inclusion instrument and avenue. However, we haven’t made the kind of progress that might have been expected. One reason is that context matters. Contextual barriers to inclusivity include:

- technology (infrastructure and affordability);

- quality (including accreditation, service and quality of the learning experience);

- cultural and linguistic relevance and responsiveness;

- perceived racial barriers;

- ‘graduateness’ and employability of open and distance learning graduates;

- confusion, conflation and fragmentation in the global open and distance learning environment.

In his presentation, Intercultural ethics: Which values to teach, learn and implement in online higher education and how?, Obiora Ike mentioned global challenges such as the rise of populism, economic and environmental problems, addictions, and issues of inclusivity. Culture matters, he argued, and from culture come values and ethics. Behaving in an ethical way engenders trust and promotes an ethical environment. Globethics.net, based in Geneva, has developed an online database of materials about ethics as well as a values framework. We must integrate ethics with all forms of education, he argued. This is a project being pursued for example through the Globethics Consortium, which focuses on ethics in higher education.

The strand Online learning and Indigenous peoples brought together papers on a variety of projects focused on Indigenous education through online tools. In the talk, A digital bundle – Indigenous knowledge on the internet: Emerging pedagogy, design, and expanding access, Jennifer Wemigwans suggested that respectful representations of knowledge online can be effective in helping others to access that knowledge. While it does not replace face-to-face transmission, cultural knowledge shared by elders online becomes accessible to those who might not otherwise have access to such knowledge, but who might wish to apply it in a range of contexts from the personal to the community sphere.

In her talk, Supporting new Indigenous postgraduate student transitions through online preparation tools, Lynne Petersen spoke about supporting Indigenous students through online tools in the Medical and Health Sciences Faculty at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. The work is framed theoretically by Indigenous research methodologies, transition pedagogies, and the role of technology and design in supporting empowerment (however, there are questions for Indigenous communities where face-to-face traditions are prevalent). There may be a disconnect between perceptions of academic or professional competency in the university system, and cultural knowledge and competency within an Indigenous community. Among the online tools created, a reflective questionnaire helps students think through the areas in which they are well-prepared, and the areas where they may need support. Future explorations will address why the tools seem to work well for Maori students, but not necessarily for Samoan or Tongan students, so it may be that as they stand these tools are not appropriate for all communities.

In the paper, Language integration through e-portfolio (LITE): A plurilingual e-learning approach combining Western and Indigenous perspectives, Aline Germain-Rutherford, Kris Johnston and Geoff Lawrence described a fusion of Western and Indigenous pedagogical perspectives. In a WordPress-based social space, each learner can trace their plurilingual journey covering the languages they speak, their daily linguistic encounters, and their cultural encounters. In another part of the website, students are directed to language exercises. After completing these, students can engage in a reflection covering questions relating to the four areas of mind, spirit, heart and body. Students can also respond to questions relating to the Common European Framework to build ‘radar charts’ reflecting their plurilingual, pluricultural identities. The fundamental aim of such an approach is to validate students’ plurilingual, pluricultural knowledge base.

Bringing together a wide range of academic and industry perspectives, this conference provided an important forum for discovering digital learning practices from around the globe, while simultaneously thinking through some of the big questions posed by new technologies.