MobiLearnAsia Conference

Singapore

24-26 October, 2012

[Continued from Day 1 blog post]

In his plenary which opened the second day, Harnessing Magic: The Mlearning Opportunity, Clark Quinn suggested that it is time to find new uses for mobile technologies. Past technologies have successfully augmented our bodies; the question now is how we might augment our brains. Of course, we do have a history of using technology to augment our brains. Books are one example. This has limitations if the knowledge changes and the books don’t. He quoted Arthur C. Clarke: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. The limitations on how we use new technologies, he suggested, are between our ears.

Learning in the past was social, but as the volume of knowledge increased, we moved into a transmission model. In the 2009 US Dept of Education study of e-learning, which found that it was superior to face-to-face learning, the researchers suggested that the improvement was not due to the medium but the chance to step back and think about how we do education. Formal learning methods are important for novices; they become less important vis-à-vis informal learning for practitioners; and for experts, informal learning is much more important.

There are four Cs of mobile learning: content, compute, communicate and capture. The first three are not unique to mobile, but the last is. It’s about capturing in context. We’re beginning to see ways in which virtual worlds connect to mobile technologies. System-generated content is also becoming important as we move towards web 3.0. Web 2.0 was about user-generated content; web 3.0 is about system-generated content, where content is pulled together on the fly. This allows us to customise the online experience and online learning. Thanks to sensors of different kinds, the technology can work with the context.

He concluded by asking what’s on the horizon. Games will be important – learning should be ‘hard fun’. Social media will be important. So will augmented reality, where information relevant to the learner can be presented in a visual interface. The fact that a device knows ‘when’ we are (as well as ‘where’) means that key information can be provided before and during a performance, and then afterwards learners can be prompted to reflect, thereby turning real-world performance into a learning opportunity. Personalisation will be increasingly possible; different people need different information flowing to them in real-world contexts. He suggested, finally, that we should consider moving away from an event-based model of learning towards slow learning. We need to develop people at the rate their brains can handle.

In the panel discussion on the second morning, a number of key points were made. Gary Woodill noted that e-learning is just the classroom placed on the screen, whereas m-learning is about learning in context. Clark Quinn suggested that there is a need for teachers to show students 21st century skills so students can learn to search for themselves and, to some extent, bypass educational institutions. We’re not yet very good at delivering chunked, distributed content. He also suggested that mobile learning designers should be asking: “What is the least assistance I can provide?” though, as Woodill pointed out, the assistance must be sufficient to help the learner achieve learning goals. Gary noted, further, that we need a design science of mobile learning.

Woodill suggested that there is a subtle shift underway from competency-based to task-based education. What matters is not what you know (there’s just too much to know nowadays) but whether you can do a task. Mobile may be about learning something quickly when you need it, and then forgetting it and moving on to the next thing. Jawahar Kanjilal asked a very important question about learners in less privileged situations: what if you don’t have a teacher, but you have a mobile phone? It becomes your teacher. Gary suggested that a mobile device can be like a faucet which filters the firehose of the internet, bringing you what you need, when you need it. The next ten years, he argued, will be the age of the algorithm, to sort out all this information. Predictive analysis will be important (e.g., see: Recorded Future, Sweden).

In his presentation, Mobile Learning Case Studies: Examples of Effective Mobile Learning, Gary Woodill outlined a number of case studies of mobile learning solutions. The audience was then asked to analyse these in terms of the design patterns. One strategy for instructional designers may be to take case studies and reverse engineer them. On design patterns, he recommended the books: Technology-Enhanced Learning edited by Peter Goodyear and Symeon Retalis, and Diana Laurillard’s Teaching as a Design Science. He also recommended the Float Mobile Learning Primer app, which contains 63 case studies.

In his presentation, Create the Future of Mobile Learning, Png Bee Hin explained that the future will see a big shift from ‘e’ to ‘m’-learning. He described the development of interactive trails by LDR using the LOTM authoring tool, which allows multimedia content and interactive activities to be delivered to smartphones (Android or iOS) using location-based technologies and a geofencing approach. The delivery of materials can be triggered using GPS, IR (image recognition) and Bluetooth. To date, they have created 42 location-based mobile trails for Singapore. The Battle for Singapore app, set up as a game, is available as a free download.

Working with the MOE, they have created trails where teachers can track students’ progress, location, activity results, and multimedia submissions (which typically include photos and videos, but can also include oral interviews and even re-enactments of historical events). It can work like a treasure hunt; students are instructed to take pictures using an IR camera at some points, and a code is pushed to them so that they can complete part of a puzzle. Students can be of all levels from primary upwards. The Singapore River Trail (see above), which was originally in English, has now been converted into Mandarin as well.

Teachers can keep track of their students, and communicate with them, from a central location. Teachers are essential to the learning process: they need to re-enter their students’ learning spaces at the appropriate moments to guide their learning. They can also create customised trails for their students, by dragging/dropping and cutting/pasting within the LOTM tool, without any need for programming knowledge. Teachers and students have even worked together to create mobile trails that map their own environment.

He concluded that location-based technologies (GPS, IR, AR) have great potential to enhance field-based learning. Having an authoring tool simplifies and speeds up deployment. The most exciting result of all, he suggested, is the finding that user-generated trails are possible.

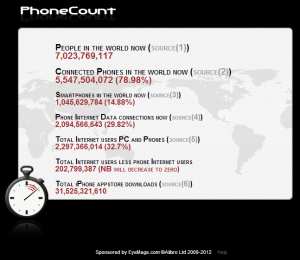

At the other end of the technology scale, but in a project with enormous potential to make a difference around the world, Jawahar Kanjilal and Bhanu Potta gave a presentation entitled Mobile-Based Lifelong Learning for the Millions: Nokia Life. In it, they looked at how mobile learning can reach under-served populations in emerging markets. This is a mobile-only paradigm for those who do not have access to the internet. Only a minority of people in the world have data connected smartphones; then there are feature phones which are data connectable; and then finally feature phones with no data, and SMS only. The projection for 2015 is that 2 billion people will have data connected smartphones; 3 billion will have feature phones (with or without data); and 2 billion will have no phone.

For many people who have mobile phones in emerging markets, it is their first phone, their first camera, and so on. They expect it can deliver many things. Information can be a great leveller for those who currently have no access to it. At every life stage there is an opportunity for informal learning. It is possible to provide content about education, health and agriculture, for example. It can’t be something which is broadcast to everyone, because it needs to be relevant to individuals and should ideally be local, even hyperlocal (how to you start saving in India as opposed to Indonesia?); it needs to be personalised.

The philosophy behind Nokia Life is: “Inform. Involve. Empower” (see: Life Tools is Now Nokia Life on YouTube). It is about “designing for personalization at scales of millions”. Emerging markets have the largest number of first generation school attendees. Parents who have a small income can pay for this service to support their children’s education. The messages can be a trigger for further offline learning. There are currently nearly 80 million users across India, Indonesia, China and Nigeria. Around 40% of subscribers overall are teachers rather than students, so teachers can use the messages as a resource in their classrooms. More than 10 million unique updates are sent out on a daily basis. SMS is used as the vehicle. It is embedded in the menu of the phone, rather than being a downloadable app. The creators considered voice at the beginning, but they were told the written word is more powerful. The users can refer to and show the written words to others.

The biggest problem was to get the content in the right format to distribute through the mobile system. Curation of content and knowledge was a major task. There are four categeories: Education (including Life Skills, Learn English, Exam Tips, General Knowledge, Dictionary), Health, Agriculture, and Entertainment. Potta gave the example of the Learn English service in China, set up with the collaboration of the British Council, where a word of the day might be given, with pronunciation, an example, and a translation. In some messages, there is a button to call a hotline for more information. Since it is too early in these markets for user-generated content, which might conflict with users’ sense of the credibility of the information, the social – or web 2.0 – aspect involves a call button, a polling function, and/or a share function.

There is a variation of Nokia Life called Nokia Life+, a web app which is designed for those who have smartphones, or feature phones with data connectability. This may be the direction in which things evolve in the future. It’s a scalable platform to reach and engage the next billion. All in all, it’s about developing an ecosystem of partners: governments, NGOs, knowledge creators. The ecosystem is beginning to build up. Nokia Life can directly support six of the eight UN Millennium Goals.

In his presentation, Cross-Platform App Development: Going Native the Easy Way, Graeme Salter listed a number of reasons for setting up educational apps, including the following:

- Improve learning outcomes

- Improve student satisfaction (e.g., convenience)

- Improve student or teacher productivity

There are, however, alternatives to having an app. One is to have a mobile optimised website (m.domainname.com). As a business, you can tap into existing apps and have your company advertised there. Another alternative is an iBook. If, on the other hand, you need an app, you should ask yourself whether it needs to be a native app. Android apps are catching up very quickly to iOS apps. Native apps have these advantages:

- Operate fast

- Can access all device features

- Don’t necessarily require an internet connection

- Have access to global marketplaces (including direct sales, in-app purchases, and advertising revenue)

On the negative side are these factors:

- Royalty fee to marketplaces

- Marketplace controls the customer information (for this reason, the Financial Times changed to a web app)

- Approval delays (even for modifications)

- Complexity of development

He suggested some solutions to these problems:

- Step 1: Create a web app

- Outsource development (e.g., Kenotopia – design an app in PowerPoint or Keynote, then outsource the coding to someone else; fiverr – will design an icon for $5; a company like oDesk or Vworker will do the whole thing. The big rewards are for ideas, not development.)

- Use tools that don’t need coding (e.g., Tumult Hype, which allows you to write HMTL5 with no coding required; you can then use JQuery Mobile, Wink, etc, to add a mobile framework so you have mobile functionality like touch, swipe, and gestures)

- Write in HTML5 (make some simple modifications to old HTML – there are few differences)

- Step 2: Convert to a native app (e.g., with PhoneGap, Appcelerator, PhoneGapBuild – you can create native apps for multiple OSs)

For an inaugural conference, MobiLearnAsia 2012 did a superb job of pulling together a great deal of national, regional and international expertise, and provided a rich forum for interactions between participants from a wide range of countries. It has also filled a gap in bringing an annual m-learning conference to the Asia-Pacific region. I look forward to seeing how things have developed when the second MobiLearnAsia conference takes place in October, 2013.