Final ‘Teaching Teachers for the Future’ Meeting

UTS, Sydney

15-16 March, 2012

The final TTF meeting wrapped up a couple of years of Federally funded work in Australia, involving all 39 universities with pre-service teacher education programmes. Part of the Australian Digital Education Revolution, its main focus was on the teacher training needed to ensure new technologies are effectively embedded in classrooms across the country.

Its 3 main components were:

1) developing graduate standards for new teachers (led by AITSL)

2) creating a base of online resources and learning objects for teachers (led by ESA)

3) conducting research and evaluation, and establishing a national network of ICT expertise

AITSL opened the main part of the proceedings by showing a video created about the national standards, simply entitled The National Professional Standards for Teachers, and giving an overview of their National Professional Standards for Teachers website (Component 1 of TTF). ESA followed up with an account of the professional learning and curriculum resources they have been developing, which will shortly be made available to all teachers (Component 2 of TTF).

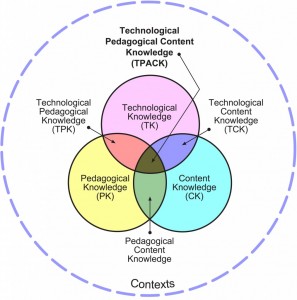

The keynote speakers, Punya Mishra and Matt Koehler, delivered a talk called T’PACK’d and Ready to Go! Back in 1999, said Koehler, the dominant view was of new technologies just as tools, which could be taught to teachers in workshops, but this didn’t necessarily mean they had much idea of how to apply the tools in the classroom. Mishra and Koehler worked with Shulman’s 1986 notion that there is a need for both content and pedagogical knowledge and, in 2004, published their initial TPCK model (represented as a triangle) and in 2005 modified it (changing it into the familiar circle format). It came to wider attention in 2006 but the acronym was unpronounceable, so they added the vowel to create TPACK, which was announced in 2007. The current model, drawn from Matt Koehler’s TPACK website, is shown below.

Koehler went on to say that a framework has to be complex enough to capture the perspectives of multiple stakeholders but not so complex that people can’t talk about it. The TPACK framework, however, is not meant to be prescriptive, nor is it meant to be complete (that is, it doesn’t cover everything a teacher needs to know). While it has been referred to in more than 300 scholarly articles, and appears in textbooks, the Australian TTF project is the biggest implementation of it to date.

Mishra pointed out that there is no such thing as an educational technology – most technologies are not in fact designed for education. As users, we are always redesigning technologies. “Only repurposing makes a technology an educational technology.” Repurposing is a creative and innovative act, with the crucial mediating role played by the teacher. These tools can allow us to break out of the box; we need to move from using technology to integrating technology to innovating with technology.

Koehler then returned to stress the importance of more work being done on measuring TPACK. To date, most work in this area has been in maths and science, but the TPACK model is meant to be broader than this.

Mishra rounded off the presentation by speaking of the importance of (in)Disciplined learning, where we think creatively across disciplines and areas. They have recently published a piece in this area called “7 trans-disciplinary habits of mind (for the 21st century)”, and their work is reflected on a website called deep-play.com. Standard solutions don’t work, he suggested: creativity is the only solution. It is time, he concluded, to explore, create and share. Putting your ideas out there, ideally under a Creative Commons licence, will bring great returns.

Glenn Finger kicked off the first afternoon by reporting on the Research and Evaluation Working Group’s major findings (Component 3 of TTF). There were three main research and evaluation strategies:

- the TPACK online surveys, which revealed measurable growth over the duration of the project in pre-service teachers’ confidence to use ICTs as teachers, and their confidence to facilitate student use of ICTs

- the Most Significant Change Methodology, which resulted in 41 stories of implementation being submitted from participating institutions, in turn revealing four categories of engagement with ICTs, namely investigation; application; integration; and extension and leadership

- facilitation of institution-led research projects and collaborations, with the upcoming Australian Computers in Education Conference, to be held in Perth in 2012, having a dedicated TTF strand

- KNOW: foundational knowledge remains important

- ACT: metaknowledge (problem solving, critical thinking, collaboration, etc) is important

- VALUE: humanistic knowledge (life & job skills, cultural competence, etc) is important

We must avoid technological determinism and see technology as embedded in social relations. Ultimately, Mishra suggested, meaning making is a transactional process – between the innovation and social structures and relationships. We need, therefore, to keep an eye on the bigger picture of technology – and of the TTF project.

Following the final keynote, the Minister for School Education, Peter Garrett, attended a series of short presentations on the accomplishments of the TTF project and responded with some comments of his own on the importance of embedding digital technologies in education.

Well that read like a sane, wise approach for Australian Education in regards to technology.

One way they can address their items of concern is to construct a situation that allows successful technology-artists to demonstrate how they use technology, in innovative art-making, to educators.

The educators then could pick and choose which methods they think would work to enhance their teaching methods.

Simply put: Artists have time to experiment, most educators do not. Therefore, let the experimenters show their most successful work, talk about it and show how it is done. The educators will be able to assess for themselves which avenues seem best for teaching.